Schools in England are more likely to receive regular reports of cyber-bullying than those in any other country in the TALIS study. How worried should we be?

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 20 June 2019

20 June 2019

By John Jerrim

There has been a lot of talk recently about the harm caused by social media and that young people are experiencing ever-greater levels of cyber-bullying. These relatively new phenomena have implications for teachers and schools, who often have to intervene in cases of unwanted electronic contact and potentially harmful social media posts being shared about their pupils.

But is this really more of a problem in England than elsewhere?

New results from the OECD’s Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018 study suggest that this may be the case. Yet, as always, the devil is in the detail. In a nationally representative survey, lower-secondary headteachers across more than 40 countries (including England) were asked how often the following occurred within their school:

- A student or parent/guardian reports postings of hurtful information on the Internet about students

- A student or parent/guardian reports unwanted electronic contact among students (e.g. via texts, e-mails, social media)

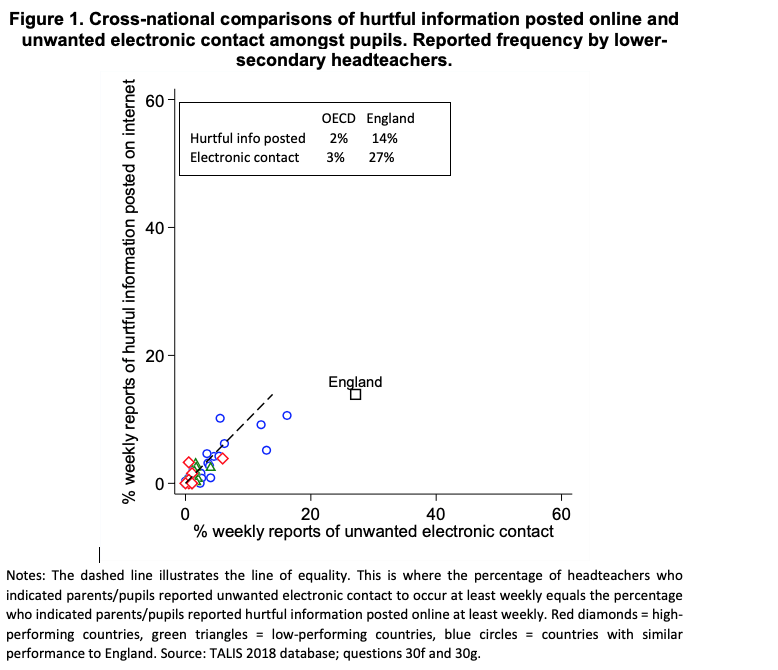

The responses headteachers provided to this question are summarised in Figure 1. This presents the percentage of headteachers who said they received weekly reports of unwanted electronic contact amongst pupils (horizontal axis) and the percentage who received weekly reports of “cyber-bulling” (i.e. postings of hurtful information – vertical axis).

England is a huge outlier in this graph. While unwanted electronic contact and cyber-bullying were only rarely reported by headteachers in most countries, this was not the case in England. Here, 27% of secondary headteachers said that unwanted electronic contact amongst pupils was reported to them every week, well above the OECD average of 3%.

Similarly, more secondary headteachers in England (14%) said that they received weekly reports of online bullying than in the average OECD country (3%).

How should we interpret this result?

Now, the instant reaction one may have to this result is to recoil in absolute horror. We knew problems with social media and cyberbullying were a concern, but we had no idea things had got this bad!

But some important caveats need to be made about these results.

First, sample sizes were relatively small. Only around 150 headteachers were surveyed in England, with a similar number participating in other countries.

Second, as with any international survey, there may be differences in translation and interpretations of the questions asked across countries. For instance, does “unwanted electronic contact” mean the same thing in England, Spain, Japan and the UAE? I don’t know the answer for sure, but this could partially explain this result. (Although England does also stand out from culturally and linguistically similar countries such as Australia and the United States).

Finally, could this result actually be a good thing? Given all the recent media attention surrounding this issue, it might simply be that schools and teachers in England are much more aware about online dangers than those in other countries. In other words, maybe this graph suggests that England is ahead of the game in recognising (and reacting) to this issue.

More evidence needed

Figure 1 is a classic example of where a research finding has raised more questions than it has answered.

Policymakers should of course take this finding seriously; it is important that there is renewed effort put into understanding how modern technology is affecting the lives of young people, their parents, teachers and schools.

At the same time, knee-jerk reactions to such apparently striking findings should be avoided. More evidence is needed before one concludes whether things are really as bad as Figure 1 initially seems to suggest.

Photo by EFF Photos via creative commons

Close

Close