Black History Month: time to explore the hidden histories of Africa

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 6 October 2016

6 October 2016

By Robin Whitburn and Abdul Mohamud

Historically, Black lives have not been deemed as important as those of white people. This goes back to the Scottsboro Boys – randomly imprisoned in the United States in the 1930s, up to Trayvon Martin and other unarmed black men shot by white men in this decade; from Kelso Cochrane – stabbed to death in 1950s London, to Mzee Mohammed – who died in police custody in Liverpool in 2015.

On both sides of the Atlantic there are serious concerns that racism has pervaded the interaction of Black people with the justice system. A serious and rigorous approach to the teaching and learning of the hidden histories of Black people of direct African descent is one way to counter the stranglehold of racism below the surface of our societies. Our book, Doing Justice to History – Transforming Black history in secondary schools, aims to equip educators and learners to take up that challenge.

In our work through Justice to History, we have developed historical enquiries that unearth the hidden stories of significant Black people and important places. Robert Franklin Williams emerged during the Civil Rights era as a campaigner in America’s Deep South, who saw the necessity of self-defence against extreme white violence and was deeply admired by Rosa Parks. Claudia Jones in London in the late 1950s, following a life of struggle in the USA as a communist and campaigner for Black equality, was the pioneer behind London’s celebration of Caribbean carnival.

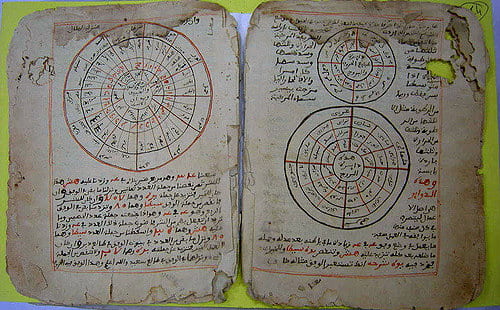

Timbuktu in West Africa, known for so long as a place of mystery and darkness, holds some of the greatest literary treasures of the medieval and early modern world. In Cardiff, men from Somalia were living and worshipping from the 1870s, when merchant ships first brought them to South Wales. Many of these histories take us by surprise; they ‘interrupt the psyche’, challenging the way we see the world, which is a major source of their significance.

Mohamoud Kalinle (image reproduced by kind permission of Glenn Jordan/Butetown Heritage and Arts Centre)

Since the seventeenth century, when Europeans started to expand the slave trade, Western scholars have denied the rich heritage of Africans’ and Africa’s past. As we highlight in our enquiry on the slave trade, the Europeans did not become slavers because they were racist, they became racist because they had profited so greatly from their traffic of enslaved Africans.

The continual denial of the significance of African history is shown in the stories of European archaeological encounters with Mapungubwe and Zimabawe in southern Africa, which feature in our Africa and Timbuktu enquiry. Europeans considered fanciful myths of a possible oriental presence there because they could not countenance the idea of Black Africans producing complex civilisations in the Middle Ages. Our proclamation that ‘Black History matters!’ is a recognition that work needs to be done to reverse the centuries of sustained systematic attempts to reject its existence or legitimacy.

Mediaeval manuscript from the Mamma Haidara Library, Timbuktu, Robert Goldwater Library, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (creative commons)

Mediaeval manuscript from the Mamma Haidara Library, Timbuktu, Robert Goldwater Library, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (creative commons)

Image of Great Zimbabwe taken by Jan Derk in 1997. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Of course other histories matter as well, but they have not been subjected to the same systematic denial and scorn across the centuries. It’s a very similar justification that is used to defend the Black Lives Matter movement that has burgeoned in the USA and is gathering support in the UK.

Do we still need a Black History Month in the UK? This October marks the 29th such celebration. In many places it has lost its way. Faced with murmurings against an exclusive focus on Black minority people, many local councils and other institutions have changed its designation to ‘diversity month’ and included a vast array of cultures within it. Perhaps unsure of much of the hidden history, organisers seem to plump for cultural events, so food and music take the place of historical controversies as the focus for many Black History month programmes.

Yet the history remains under-exploited and young people continue to think that Black history means slavery and American Civil Rights. Doing Justice to History involves teaching and celebrating a wide range of Black histories that will show that scholars like Georg Hegel in the early 19th century and Hugh Trevor-Roper in the mid-20th were tragically wrong to declare Africa ‘not worthy of historical research’ before Europeans arrived.

Black History Month is an opportunity to highlight the work of the pioneers who are still battling established master-narratives that marginalise Black history. The goal is indeed to establish Black histories within the standard narratives and enquiries of our schools, colleges and universities, all year round. When the psyches of our people no longer need interrupting, we can consider retiring our Black History Month programmes. Meanwhile the struggle for justice continues.

Close

Close