Academy conversions: why money doesn't always talk

By Blog Editor, IOE Digital, on 12 July 2012

Rebecca Allen

Thousands of primary and secondary schools have chosen to convert to academy status (the chart below covers secondary education). A survey by the think-tank Reform showed that financial considerations were the most widely cited reason for conversion, as predicted by many, including The Guardian.

The financial gains arise because academies can directly claim their share of the Local Authority Central Spend Equivalent Grant (LACSEG) (pdf) in recognition of the fact that as independent schools they no longer receive a number of services from local authorities (LAs), and must make appropriate provision for themselves or do without these services. LACSEG money is spent by local authorities on:

- Educational disadvantage: pupils with special needs but without statements, behaviour support services, educational welfare services, 14-16 practical programmes, assessing free school meals eligibility

- Educational enrichment: music services, visual and performing arts, outdoor education, museum and library services

- Risk sharing across schools: coverage of long-term sick, termination of employment costs, redundancy costs, capital asset management

- Shared administrative functions: school admissions, statutory and regulatory duties.

If financial considerations have indeed been a primary motivator for conversion, then is it also true that those with the greatest potential gains from conversion have done so in the greatest numbers? If this were true, then I suggest we should be able to identify likely converters using the following four criteria.

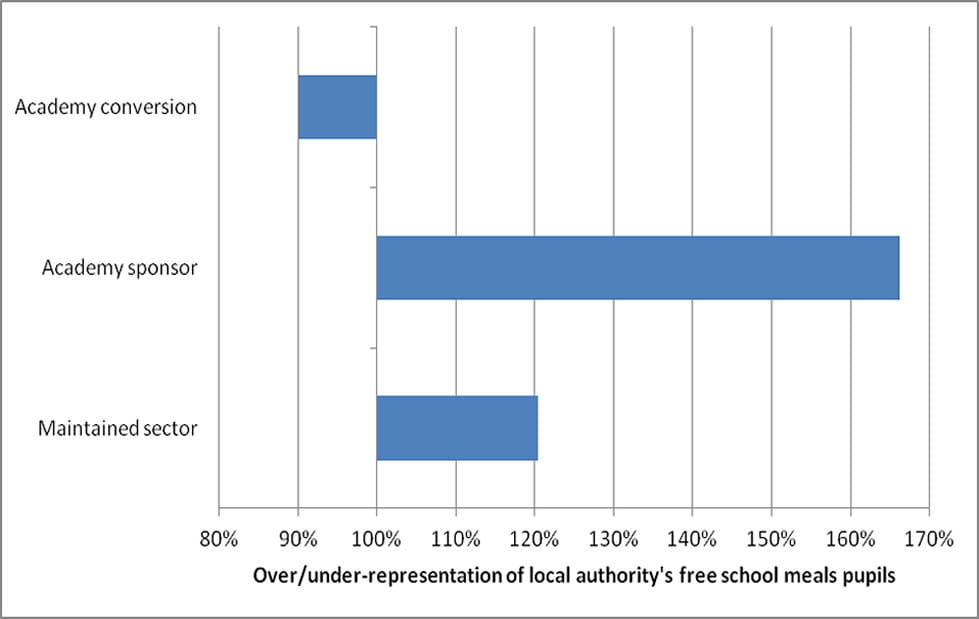

1. Affluent schools within less affluent local authorities have most to gain from conversion

The share of LACSEG given to academies was calculated on a simple per pupil basis, yet a large proportion of LA services are used to support children with challenging educational needs. The smaller the local authority’s share of children from deprived backgrounds you take, the more you can benefit by taking your school’s LACSEG funding out of the central pot of money. Academy converters are indeed far more affluent (at under 9% free school meals eligibility for secondary schools) than the remaining state maintained sector (around 15% free school meals eligibility). It is also true that academy converters take a disproportionately lower share of the LA’s free school meals population.

2. Potential benefits of academy conversion are highest in areas with a high LACSEG (as calculated by DfE)

Where a local authority’s LACSEG spending, as estimated by DfE on their website, is very high, local schools have the most to gain on a per pupil basis from academy conversion. But data actually show the local authorities that have lost the greatest numbers of schools to conversion are actually those with low LACSEG spending.

3. Benefits should be highest in areas where the discrepancy between DfE-calculated LACSEG and ‘true’ LACSEG were highest

Many schools realised that they would receive a significant short-term windfall from conversion because the DfE had incorrectly calculated the current expenditure on LACSEG services by local authorities. The discrepancy between calculated LACSEG and true LACSEG in an LA is anywhere between zero and almost £500 per pupil.* We might therefore expect that conversions were highest in areas where this discrepancy was particularly high. But the data show this isn’t so. In fact, some of the areas with the highest discrepancy in their calculation have had no secondary school convert to academy status (e.g. Islington, Barking and Dagenham, Hartlepool).

4. Those in most financial need – with deficits or falling populations – should be most likely to convert

Some schools argued that they felt they had no choice but to convert to academy status to compensate for cuts in funding to their school. It is true that many schools have seen falling income year-on-year, but if this was an important motivator for conversion then those in the most financial need should have been most likely to convert. However, data show that those already in deficit in the 2009/10 financial year (the most recent for which we have all-England data) were no more likely to convert than others. Also, those with falling pupil populations were also no more likely to convert.

So, although those schools that have converted to academy status so far widely cite financial considerations, the characteristics of the converters are not as predicted if this were the sole consideration. What can we conclude from this? It is possible that many heads and governors do not have the right financial data to make the decisions about conversion, and had they done so, even greater numbers would have recognised the short-term windfall and so converted. Or alternatively political considerations for those sitting on governing bodies widely influenced the conversion decision, which is why more Conservative local authorities have seen the greatest rates of conversion. However, we should also not dismiss the idea that, at least in some local authorities, the sense of cohesion across local schools remains very high and that they value the quality of the services the local authority provides to help them provide schooling for children, particularly those in more challenging circumstances.

* Thanks to Chris Cook of the Financial Times for these estimates

One Response to “Academy conversions: why money doesn't always talk”

- 1

Close

Close

Reblogged this on Rebecca Allen.