By Rachel Benchekroun and Avril Keating

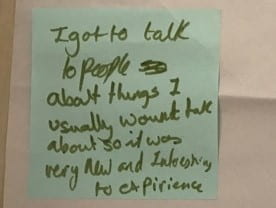

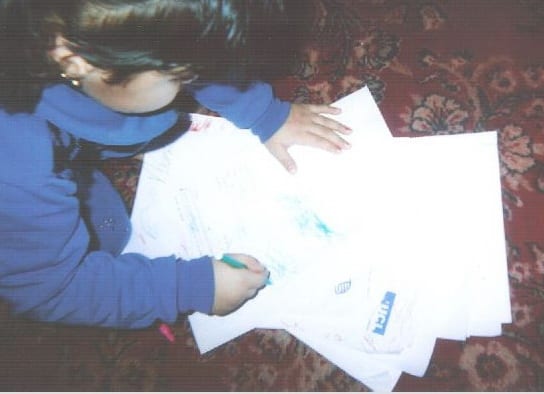

The initial discussions with the Year 10 students in Margate suggested that there were key areas of the town that young people did not feel were safe or accessible. To try to identify the spaces and places that young people do feel they can use, Rachel asked the students to draw maps of their town.

For this exercise, the students were given about 5 minutes to create a map to show where they go and where they feel safe. The maps they produced highlighted the different types and levels of mobility within the group.

Home – School – Home

Several students said they do not go anywhere other than walking from home to school and back; this was reflected in their maps, which either depicted just their bedroom or house, or represented their home and school and the trajectory between the two. Jessie (female, 14), for example, drew her house and the corner shop, showing her movements between the rooms of the house and to and from the shop, where she said she goes to buy crisps.

Meanwhile, Sam’s map consists of a plan of his bedroom (taking up just one small corner of the page), with an image of the TV and PlayStation that he uses for entertainment, and a table ‘where my chicken is’.

Jessie’s map

Sam’s map

This tendency to stay so close to home can be explained in part by fact that contemporary teenagers spend more time in their homes than previous generations. Although they remain within the home, Ito et al (2009) argue that we should not automatically assume contemporary youth are more isolated; instead, they are often engaged in online forms of ‘hanging out’ that replicate the youth activities (e.g. chatting, gossiping, collaborating) that used to happen ‘offline’. However, while this may be true for Sam, Jessie told us she spends so much time at home because: I don’t have friends to go out with. […] I stay at my house. I don’t go anywhere.

In this town, another possible reason that young people spend so much time at home is that they felt that going out was unsafe. Parts of Margate are plagued by high rates of crime, and its young residents are particularly vulnerable to some of these criminal activities. As a result, it is perhaps no surprise that one student told us:

I do like Margate but […] I don’t feel safe. I stay at home unless I go out with my family, like once a month for the community activity. My mum says not to go out because there are gangs. […] I don’t go out. I stay at home.

Making local spaces their own

When the students do stray beyond home or school boundaries, they told us that they tend to hang out at cheap shops and supermarkets in the town centre (such as Aldi, Lidl and Poundstretchers) or the large retail park that was on the outskirts of town. This continues the long-standing tradition of teenagers hanging out on the high street, but it also reflects young people’s often limited resources, and their limited access to, and exclusion from, various forms of public spaces (Ito et al, 2009, Shaw et al, 2015).

These retail spaces are not targeted at young people, but the students were creative in their use of these places and found ways of making them their own. Lydia and Evangeline (14), for example, took great delight in co-producing a large picture of the local supermarket where they claimed to spend most of their time. Lydia explained: “it’s my favourite place. It’s my home away from home.”

Rachel: How often do you go there and why?

Rachel: How often do you go there and why?

Lydia: I live there, it’s my house! [laughs]

Teacher: Do you hang out IN [the supermarket] or outside?

Lydia: Both.

Teacher: What about the security guy?

Lydia: We play ‘Double Double This This’ [a clapping game] with him.

Lydia and Evangeline are thus an example of young people claiming urban spaces through ‘playful encounter’ and creating ‘momentary micro-atmospheres of joy’ (Pyyry and Tani 2017, Pyyry 2016). As young people ‘hanging out’, they ‘take part in urban life and in the creation of its fleeting atmospheres. They are involved with places that are important to them and claim these as their own, even if just temporarily’ (Pyyry and Tani, 2017, p.12).

Tourist areas = not spaces for local youth?

Of course, Margate has lots of non-retail local amenities, and some of these were reflected in some of the students’ maps. In these maps, the key landmarks that were featured were the beach, Dreamland amusement park, and the Turner Contemporary Art Gallery in the centre of Margate. Yet, while some of students did utilise these places, the subsequent discussion revealed that most did not. The students’ more typical relationship with these places is reflected in Lydia and Rory’s discussion of the latter’s map:

Lydia: My dear friend, why do you enjoy visiting those places?

Rory: I don’t enjoy going to those places… I just put [them] there for effect. Turner, I never go. Sometimes I go to Ramsgate Fried Chicken. I visit Tivoli [area of Margate] quite often. I hang out there.

In short, these sites tended to be viewed as spaces for tourists, not for young people that live in the town.

What do the maps tell us about youth mobility?

Th e students’ maps indicate that most have low levels of geographical mobility, even within their own town. Most of the young people focused on the micro-scale, and the (very) local environment. The one exception to this was James who, in contrast to the others, drew a detailed map of the Thanet district, showing not only Margate but other towns in the region, with arrows towards other towns, including London. James even included a key along the side of the map, to indicate how often he visits them.

e students’ maps indicate that most have low levels of geographical mobility, even within their own town. Most of the young people focused on the micro-scale, and the (very) local environment. The one exception to this was James who, in contrast to the others, drew a detailed map of the Thanet district, showing not only Margate but other towns in the region, with arrows towards other towns, including London. James even included a key along the side of the map, to indicate how often he visits them.

This geographically-rich map provided a striking contrast with the other maps, but as this was a pilot project, we did not have an opportunity to explore why James focused on his connections with the wider region, rather than with the local town as the others did. One avenue we would like to explore in the future is if his greater exposure to mobility indicated (a) an increased propensity to be more geographically mobile in the future and/ or (b) a greater likelihood of social mobility in the future. As Skrbis et al (2014) point out, mobility is now widely treated as a passport to a better future for young people. As a result, the dynamics of globalisation mean that, for this generation of young people anyway, geographical and social mobility are closely intertwined.

This project was funded by the UCL Grand Challenge small grant scheme in association with the UCL Grand Challenge of Cultural Understanding.

Filed under Uncategorized

Comments Off on Mapping young lives: what are the spaces and places that young people use in coastal towns?

Close

Close

ncil in South Africa, an Adjunct Professor of Philosophy at the University of Fort Hare and an adjunct Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Cape Town. She holds undergraduate degrees from the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Zululand in South Africa; a Master’s degree from Harvard University and a PhD from the University of Cambridge. Her expertise and current research centres on the just inclusion of youth in a transforming society that includes interpersonal and communal notions of restitution. Her work is characterised by a focus on Southern theory, emancipatory methodologies and critical race theory. Before embarking on graduate studies, Sharlene spent 12 years at a youth NGO where she pioneered peer-led social justice programmes for school-going youth. She has published widely in academic journals and has authored or edited multiple books including Ikasi: the moral ecology of South Africa’s township youth (2009); Teenage Tata: Voices of Young Fathers in South Africa (2009); Youth citizenship and the politics of belonging (2013); Another Country: Everyday Social Restitution (2016), Moral eyes: Youth and justice in Cameroon, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and South Africa (2018) and Studying while black: Race, education and emancipation in South African universities (2018). She is the President of the International Sociological Association’s Sociology of Youth research committee and is the chair of the board of the Restitution Foundation, an NGO in South Africa.

ncil in South Africa, an Adjunct Professor of Philosophy at the University of Fort Hare and an adjunct Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Cape Town. She holds undergraduate degrees from the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Zululand in South Africa; a Master’s degree from Harvard University and a PhD from the University of Cambridge. Her expertise and current research centres on the just inclusion of youth in a transforming society that includes interpersonal and communal notions of restitution. Her work is characterised by a focus on Southern theory, emancipatory methodologies and critical race theory. Before embarking on graduate studies, Sharlene spent 12 years at a youth NGO where she pioneered peer-led social justice programmes for school-going youth. She has published widely in academic journals and has authored or edited multiple books including Ikasi: the moral ecology of South Africa’s township youth (2009); Teenage Tata: Voices of Young Fathers in South Africa (2009); Youth citizenship and the politics of belonging (2013); Another Country: Everyday Social Restitution (2016), Moral eyes: Youth and justice in Cameroon, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and South Africa (2018) and Studying while black: Race, education and emancipation in South African universities (2018). She is the President of the International Sociological Association’s Sociology of Youth research committee and is the chair of the board of the Restitution Foundation, an NGO in South Africa.