The Colouring Book Information Sheet: Involving Young Children in the Research Process through Informed Assent

By UCL Global Youth, on 12 March 2019

A guest post by Sandra El Gemayel, a PhD Candidate at UCL, Institute of Education

In recent years, research with/for/about children and young people has been on the rise. Minors have started being recognised as experts in their own lives, with a voice and with agency, prompting researchers to include them more centrally in research studies. With more and more children being involved in such projects, how might researchers ensure that the young participants truly understand the aims of the study and their role in the research process? In this article, I describe the steps that I took as a PhD researcher to gain child participants’ informed assent and discuss some challenges that arose along the way.

In recent years, research with/for/about children and young people has been on the rise. Minors have started being recognised as experts in their own lives, with a voice and with agency, prompting researchers to include them more centrally in research studies. With more and more children being involved in such projects, how might researchers ensure that the young participants truly understand the aims of the study and their role in the research process? In this article, I describe the steps that I took as a PhD researcher to gain child participants’ informed assent and discuss some challenges that arose along the way.

Having started my PhD in January 2016, I planned to move to Lebanon in May 2017 to conduct fieldwork with young Iraqi and Syrian children (4-8 years old) who had fled their home countries due to armed conflict. My aim was to study the impact that armed conflict and displacement had on those children’s childhoods and on their play. As my methodology included interviewing young children using participatory methods and adopting a ‘Day in the Life’ approach (see Gillen & Cameron, 2010), spending a whole day observing the children using a video camera, I wanted to make sure that the participating children clearly understood what was being asked of them before they gave their assent to continue with the study.

I conducted a literature search on gaining children’s informed assent and landed upon Pyle and Danniels’ (2016) article Using a picture book to gain assent in research with young children. The authors created an ‘assent picture book’ for the young children participating in their study and included photographs of one researcher and two young children enacting every stage of the research process. Each photograph was followed by a short description. While this method of gaining informed assent seemed appropriate to adopt, the practicality of creating the picture book proved challenging. My supervisor and I considered the time it would take to find children who could be featured in the picture book, to receive consent and assent from the parents and children, to apply for ethics in order to use children’s photographs in the picture book and to finally take the photographs, and decided to take a different approach.

Drawing on the ‘assent picture book’, I created a colouring book, replacing photographs with cartoon outlines depicting the different stages of the research process. After a few failed attempts at drawing the cartoons myself, I ended up searching for images online. I included images of activities the children would be involved in such as playing, drawing, building with blocks, and taking photographs using disposable cameras. I also included images of the recording equipment I was to use, a video camera and a voice recorder. I chose drawings that most closely reflected the activity or object at hand in order to avoid misrepresentation, misunderstandings and disappointment, and each image was accompanied by a short description. I sent in the colouring book and other documents alongside my ethics form to the UCL IOE Ethics Committee and, once I received ethical approval to begin fieldwork, I personally translated the colouring book from English to Arabic, the language spoken by the participants.

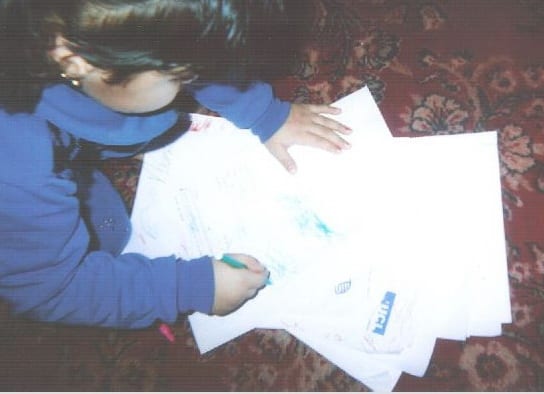

Following recruitment, I visited each child’s home and, after receiving parental consent, went through every image in the colouring book with each child, explaining why I was there, what I wanted to do, and what was expected of the children. I also distributed extra copies of the colouring book to the children’s siblings. The colouring books proved to be very successful. The case study children pointed to their favourite images, actively asked me questions about the images, and coloured them in with great focus and excitement using colouring pencils that I had provided. The children also referred back to the colouring books during follow-up visits.

Continuing the Consent Conversation

Ongoing assent throughout the research process was also one of my top priorities. I wanted the children to feel comfortable letting me know whether or not they wanted to take part in any activity, and it was my ethical responsibility to abide by their decisions. I had previously tried out a method to gain ongoing assent when conducting fieldwork for my MA dissertation. I had created a red ‘STOP’ sign and a green ‘GO’ sign that the participating children could hold up to signify whether or not they wanted to take part in any activity. However, the signs were not very successful as the children regularly held up the wrong sign while giving assent or dissent. Moreover, the signs soon turned into ‘swords’ that the children integrated as props in their play and, although this was an interesting observation, it was obvious that the signs did not serve their intended purpose. Therefore, for my doctoral study, I decided to use a simpler method to gain assent: making a Thumbs Up or Thumbs Down sign. Images of a Thumbs Up and a Thumbs Down sign were represented in the colouring books, and were easily understood by the children. The children appeared to be familiar with the images, as all of the case study children linked the thumbs up sign to the ‘Like’ button that is used on Facebook.

While this method of ongoing assent worked well, I was conscious that the children did not always actively voice their assent or dissent. As a result, I took it upon myself to observe the children’s behaviour as I filmed them, or as I asked them to take part in certain activities. If at any point I felt that the children were uncomfortable or unhappy with my presence or my request, I asked them what they would like me to do and continued or discontinued the activity accordingly.

Conveying the aims of a research study to participant children and young people can sometimes be challenging. However, thinking practically and creatively to portray information in an age-appropriate and accessible manner can go a long way to ensure ethical research practice.

This research project was funded by the Froebel Trust and by University College London.

Close

Close