The immigrants ‘crisis’ and the limits of Facebook

By Razvan Nicolescu, on 18 May 2015

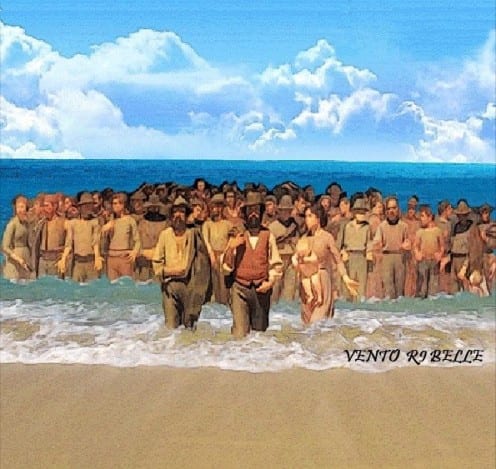

Photomontage realised by Vento Ribelle and posted on their Facebook page on the 20 April 2015 and shared by left-wing individuals in Grano.

This post is prompted by the continuous tragedy represented by the immigration from North Africa on the shores of south Europe. Data shows that over 23,000 people have died since the turn of the millennium in attempting to reach Europe, most of whom drowned in the Mediterranean Sea. This is about 50% more than the official estimations.

The most dangerous route is the one between North Africa and South Italy (mainly the Isle of Lampedusa) estimated to have seen almost 8,000 deaths in this time interval, followed by the Eastern Mediterranean route (between Greece and Turkey), and the West Mediterranean one (between Canary Islands and Spain).

In Italian media, the most common term used to describe this phenomenon is ‘tragedy’, and the Mediterranean Sea is deplored as a ‘cemetery’ or ‘battle camp’. The Italian authorities are undertaking the enormous effort to save the lives of immigrants and direct them to the overpopulated reception centres. Very recenlty the Italian Navy saved 4,000 migrants from the Strait of Sicily and one migrant woman gave birth to a baby girl on an Italian warship. In 2014 the operation ‘Mare Nostrum’ operated by the Italian authorities cost 144 mil EUR and was estimated to save more than 150,000 people in 421 sea interventions. According to the Italian officials, the number of people in Italian reception centres is currently almost 70,000, out of which 14,000 are unaccompanied children.

Since I started fieldwork in April 2013, the issue of immigration on the southern Italian shores was a central concern in Italian media. This was equally reflected on Facebook: each time a tragedy happened people used to share news and moving photos from mainstream journals on the platform. Most people who posted personal comments were deploring the existing situation and accused the larger international context of not taking appropriate action. The political left accused the immorality of Western world that did nothing to reduce poverty, inequality, and stop the numerous conflicts in Africa and Middle East, while the political right accused Europe of virtually leaving the southern countries of the continent alone in their fight to stop the death toll caused by illegal immigration.

Some directed their criticisms towards European Union and officials who did not recognize this as a European crisis and left some of the most impoverished countries, such as Italy, Spain, and Greece to solve it by themselves. Others accused the politicization of the crisis, as they saw that most political interventions, especially those from outside Italy, do not focus on the reasons of this crisis, but on ways to reduce immigration and requests for asylum.

But overall, most people in Grano had a profound sense of helplessness when confronted with the press reports on the never-ending tragedies. The general sense was that this was a humanitarian crisis that nobody really had control over; Italian authorities were simply obligated to react promptly and save lives.

This is one example when public social media mirrors the mainstream media. Both average people in Grano and leading editors in national journals share the sense that their voices are not heard by policy makers and that there is little will from the international community to solve some of the issues that cause migration in the first place.

In this context, the problem raised by this post is the inefficiency of social media to really influence the international agendas in the short term. The fact that people can act extremely fast on social media gave many the idea that their governments and international players should also act more promptly than they used to. And when they see this is not happening, many are disillusioned. They see that higher political forces simply disregard their concerns as expressed on social media.

Many people in Grano contrast this to the efficiency of some transnational agencies and influential social activists that use social media to sustain and promote their respective projects, whether these are political or humanitarian. The frustration comes from the fact that a media that is announced as being global and effective in nature, proves to be extremely limited and ineffective for most people.

This is reflected in one of the findings of the Global Social Media Impact Study that argues that most of the time, rather than representing global forms of socialization and information, social media is extremely local and specific.

In Grano, Facebook encompasses a strong emphasis on the local through photography of local sea and landscape, food, and traditions, and opens to broader issues through memes with moral implications, anecdotal content, and criticisms of the (usually) national politics. In this equation, the wave of people seeking a better life in Europe is seen as a ‘crisis’ and social media reflects the inertia of conventional media and European society at large.

Note: This seems to be the biggest social and humanitarian problem in contemporary Europe; it seems to be a response to the process of self-closure that sociologists and historians have remarked Europe has undergone in the last century. In this sense, it is a revolution. One main difference to the anti-governmental movements in recent years is that the migrants’ revolution is not promoted on social media, maybe because it does not have leaders, but there are common people who want to tell us something. The first step is to listen to them.

Close

Close