Social media and the shifting boundaries between private and public in a Muslim town

By Elisabetta Costa, on 26 March 2015

Photo posted on the Facebook profile of a research participant

Facebook is designed to encourage people to reveal information about themselves, and the market model of Facebook’s founder Mark Zuckerberg is based on sharing and radical transparency (Kirkpatrick, D. 2010). Also, scholars have largely focused on the “disclosure effect” of Facebook, and have studied the ways this social media has led people to publicly display private information about their daily life.

In Mardin, however, people are really concerned about disclosing private information, facts and images. I’ve been told several times by my Mardinli friends, that the public display of photos portraying domestic spaces and moments of the family life was sinful (günâh) and shameful (ayıp). The variety of the visual material posted on Facebook in Mardin is, indeed, quite limited compared to what we are used to seeing on the profiles of social media users in other places, like London, Danny, Jo or Razvan’s fieldsite. For example when people in Mardin organise breakfast, lunch or dinner at their house, and invite family’s friends and relatives, they rarely post pictures portraying the faces or bodies of the participants at the feast. They rather prefer to show pictures of the good food. In this way they can reveal and show off their wealthy and rich social life, and at the same time protect the privacy of the people and of the domestic space. Yet, when images portraying people inside the domestic space are publicly displayed, these tend to be very formal and include mainly posed photography. By doing so, the aura of familiarity and intimacy is eliminated, and the pictures are more reminiscent of the formal images common in the pre-digital era.

Whereas in most of the cases people tend to follow online the same social norms regulating the boundaries between private and public offline, it’s also true that these boundaries have increasingly shifted. The desires of fame, notoriety and visibility is very strong among young people living in Mardin. For example, after posting a picture, it’s quite common to write private messages to friends asking them to “like” the image. I’ve also been told off a few times by my friends in their early twenty, for not having liked their pictures on Facebook. Facebook in Mardin is a place to show off, and to be admired by others. It’s the desire of popularity and fame that has led people to publicly display moments from their daily life that have traditionally belonged to the domestic private spaces. By doing so, the private space of the house has started to increasingly enter the public space of Facebook, despite limitations and concerns. Also the body and the face of religious headscarf wearing women have been widely shared on the public Facebook, apparently in contrast with religious norms. A friend told me: “Facebook brings people to behave in strange ways. A religious covered woman I am friends with, on Facebook posts the pictures with her husband hands by hands” This public display of the conjugal life contrasts with the normative ideas Muslims from Mardin have of the private and the public. Several other examples show that Facebook has led people to publicly display what has traditionally belonged to the domestic and private sphere.

In Mardin the culture of mahremiyet, the Islamic notion of privacy and intimacy (Sehlikoglu, S. 2015), continues to regulate the boundaries between the private and the public both online and offline, but with significant differences between the two.

References

Kirkpatrick, David. 2010. The Facebook effect. Simon and Schusters

Sehlikoglu, Sertaç. 2015. “The Daring Mahrem: Changing Dynamics of Public

Sexuality in Turkey.” In Gender and Sexuality in Muslim Cultures. Gul Ozyegin

(Ed), Ashgate.

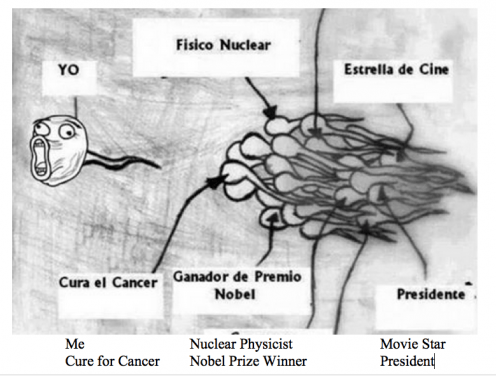

Self-Deprication

By ucsanha, on 23 March 2015

I recently wrote about the ways that northern Chileans express normativity on social media, using Kermit the Frog and contrasts between “Expected” and “Reality” memes as examples. But perhaps what demonstrates a desire for normativity even further is the way many individuals in Alto Hospicio express self-deprecation.

Much like the contrasts between expectation and reality, self-deprecation memes work to set up a contrast between idealized subjects and normativity. They may present an example of ambition, success, or a luxury lifestyle, yet do so through a frame of exaggeration. They then place themselves as a representative of normality, which contrasts with the ridiculousness of the exaggeration. In doing so, the humorous context allows them to adhere to normativity in an active sense. Rather that it being an implicit contrast to ambition, normativity is actively cultivated as an important value.

The photo above is just one example of self-deprecation in which the sperm that fertilizes the egg somehow outruns those that could have produced exceptional offspring: a Nobel Prize winner, a president, a movie star. “Me” is contrasted with these exceptional possibilities and is thus assumed to represent the ultimate ordinary possibility.

Other forms of self-deprecation involve references to the imperfect body (“A man without a belly is like a sky without stars”), academic credentials (A cemetery headstone engraved with “Here lie my ambitions to study), or material possessions (A picture of a rusty broken down car overlaid with the words “What do you say if I try to seduce you in my car tonight?”). These examples present the person who posts them as representative of the ordinary person who doesn’t live up to ideals that are considered to be out of reach. Instead they frame these more ideal forms as ridiculous through distancing. Sometimes they even explicitly spell out the benefits of normativity. One popular meme reminds readers that “Being ugly and poor has its advantages, when someone falls in love with you, they do it from the heart.” Again the poster of the meme positions them as ugly and poor, yet expresses happiness because this verifies the authenticity of relationships. Being ordinary means one doesn’t have to worry about being liked only for superficial reasons.

Self-deprecating humor is especially important, because it allows divergent self-representations to surface in ways that may be more accessible (both to the person who expresses the sentiment as well as to their audience) than literal expressions of ambition. Self-deprecating humor allows for play without alienating the audience because that which is outside of normativity is presented in a nonthreatening way (Ritchie 2005:288). In the context of normativity in Alto Hospicio, joking is a safe, and obviously popular way for people to express things that might not be acceptable otherwise.

References:

David Ritchie “Frame-Shifting in Humor and Irony” Metaphor and Symbol 20 no. 4 (2005):275-294.

A (Pre- ) Theory of Non-Usage

By Jolynna Sinanan, on 12 March 2015

Photo by Tom Jutte (Creative Commons)

Now that we are heavily into writing our individual books on social media, it’s the time to think about the original insights we have gained from our fieldwork in relation to wider themes and issues. This month, I want to deal with non-usage. Generally, Trinidadians are keen to be up to date; with fashion, pop culture and uses of new media. Trinidadians were very enthusiastic to embrace using the internet generally (see Miller and Slater, 2000) and similar to their use of Facebook, internet usage was more of a product of social norms and perceptions than it was a product that was exported from Silicon Valley.

I can appreciate that even the term ‘using the internet’ is outdated, I’m ‘using the internet’ throughout the whole process of writing and publishing this blog post but accessing the digital ether has become so normal and ubiquitous that we wouldn’t think of checking our email on our phone as ‘using the internet’.

I want to deal with an aspect of non-usage that I have called ‘digital resistance’. As resistance implies, there is a wilful refusal to something that is an imposed (or forced) expectation. There are two main reasons that drive digital resistance that came out of my fieldwork. The first is that people refuse to adopt technology for more social communication because their lives are already socially saturated, meaning that people already have too many face to face relationships (mostly family and extended family) that are demanding of people’s time. There are already enough expectations, obligations and negotiations digital resistors have in their lived social relationships that they don’t want to ‘keep up with the times’ or ‘get on board’. New communications media add yet more modes of conduct that they have to negotiate and strategise and learn for their relationships. They feel they become more mediated.

The second reason has a lot to with the first. For people who ‘opt out’ of using new media beyond a basic mobile phone for personal communications, social media not only represents an increase in mediation in already complicated relationships, but it also represents a lifestyle that directly or indirectly opposes their immediate way of life and values. There are gender, age and class dimensions that are intertwined with the values of people’s immediate way of life and why they would not want to be associated with using new media. For example, there were research participants who have the latest smart phones or keep up trends because they enjoy a lifestyle of having the newest fashionable things. The other side is that for people consider themselves as being more ‘traditional’, keeping up with technological trends and adopting social media means that their way of life, where they see face-to-face communication as more authentic, becomes less valued. Their social circles, for example, groups of mothers who are housewives, or farmers where all their friends are farmers, are made up of people with shared circumstances and values. These participants often frame not using social media as ‘not having the need’, but it is also that they don’t associate with groups who see social media as central to their social lives.

When we think about people who don’t use the internet regularly, or who don’t own smartphones, their reasons might not be so straightforward, or even easy or obvious for them to explain.

Cooking Soup Online and Being a Good Mother

By Xin Yuan Wang, on 9 March 2015

Images of soup on Chinese social media

In order to analyze people’s postings on QQ or WeChat I had to spend a lot of time viewing and recording my informants’ online postings, especially the photos and other images they posted on their social media profiles, and then categorize different kinds of images into different genres.

Among all the images, ‘food’ photos turned out to be one of the major genres which people frequently post online. ‘You are what you eat’- food is such an important part of Chinese perceived cultural experience, the use of food to express sophisticated social norms is highly developed in China (1). As Kao Tzu, a Chinese ancient philosopher said, ‘Shi Se Xing Ye’ (the appetite for food and sex is human nature). And a Chinese saying goes ‘Min Yi Shi Wei Tian’ (Food is the paramount necessity of the people).The importance of food in everyday life is also reflected in greetings. For instance, instead of asking “How are you?” it is quite normal to ask “Have you eaten?” Division of a stove is symbolic of family division (2). One of the most insightful anthropological discussions of communal dining in China is Waston’s (1987) study on Sihkpuhn (to eat from the same pot) banquet in a Hong Kong village. As Waston argues, eating from the same pot serves to ‘legitimize a social transition’, for instance, a marriage without Sihkpuhn feast is not considered legitimate; the social birth of males and heir adoption are both marked and celebrated by Sihkpuhn feast. This is why the family reunion meal is so important for every family member, it is not only a time to enjoy delicious and various foods and drinks, but an occasion to unite a family together. Every family member in the reunion dinner, eating from the same pot, represents a family collectivity and is therefore “eating for others”. It also seems that, especially among rural migrants, food and the feeling of ‘being at home’ when one is working far away from one’s homeland is closely connected.

All the previous study on Chinese food as above seems to have provided the convincing reason of ‘why food postings are so popular among Chinese people on social media’. However, curiously, when I counted the ‘food’ photos and images I found there is one specific kind of Chinese food was most popular among young mothers, which is soup. Why soup? The answer seems go beyond the Chinese social norms about ‘food’ in general- there must be something more specifically about mothering.

During my field work, I found that one of the typical criteria of a ‘good mother’ among my informants is to ‘cook well’ as many of them put it. From time to time, people told me that the thing they miss most when working outside is their mother’s cooking. Here the social implication of mother-child bond through the image of mother’s cooking seems to go beyond the real taste of the food. It is widely believed that food is a kind of medicine which helps to strike the balance of the ‘Qi’ (air, vitality) of one’s body in daily life, according to the philosophy of Chinese cuisine. In addition, among all kinds of Chinese cuisine, soup is unquestionably regarded as the one which can nourish one’s ‘Qi’ best. In my field site, the best way people could treat, me as they believed, was to feed me a lot of homemade food in overwhelming and non-stop manner. And from time to time it felt extremely difficult to say no when women started their lines like “oh it took me the whole day/ whole afternoon to prepare and cook this soup, and you have to have some, very good for you body!” Cooking a decent soup usually requires a very long time, a lot of patience, delicate heat control and decent knowledge of food material.

In a way, the process of preparing and cooking a decent soup is similar to ‘mothering’ – it’s always time-consuming, and you need a lot of patience, understanding and good control of the ‘heat’ in the relationship. Thus the frequent sharing of soup photos seems to just reinforced the widely accepted image of a good mother.

It’s universal that women feel anxious about becoming a mother, and a wise strategy to deal with such anxiety among young mothers in my field site seems to be posting a lot of ‘soup’ photos on their social media profiles. That is to say, before they cook the ‘real’ soup for their kid, they have cooked the soup online to prepare to be a good mother.

Reference:

(1) Watson, James L. 1987. “From the Common Pot: Feasting with Equals in Chinese Society”, in Anthropos, 1987 (82): 389-401.

(2) Stafford, Charles. 1995. The Roads of Chinese Childhood: Learning and Identification in Angang. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p4

How much hate is there on Facebook?

By Razvan Nicolescu, on 2 March 2015

One of the 10 best memes of 2013 according to wired.com

This blog post was inspired by one question Sonia Livingstone asked the Global Social Media Impact Study team after our joint presentation at SOAS. The question was addressing the relation between emotions and social media and in particular to what extent we agree with the stereotypical image that sees social media as the default display for negative comments and interventions.

In the first part of my answer, I was arguing that seldom ‘the negative’ is already in the gaze of many observers of social media. Sometimes, negative news, heated discourses, and reports of intolerance are so poignant and invite to instantly share that they gain a kind of momentum that clearly stands apart from any other type of information. Then, everyday online conversations could allude to the ‘theme of the day’ as it were.

But, after 15 month of fieldwork in southeast Italy I cannot really say that ‘the negative’ dominates social media. By contrary, if we take a look at the Facebook pages of people in Grano in any given day and apply some simple statistics, we will see that most of the times the negative comments represent less than 10% of the total number of comments, while sometimes they are negligible, hatred is virtually absent! Instead, people really prefer irony and wittiness to express their various disappointments and discontents on a daily basis.

This points to the issue that in what regards news, social media behaves quite similar to a classical broadcast medium such as TV; the main differences rest in its real-time, broadness, and reproductive nature, as well as in the possibilities of (usually) horizontal interaction using the same environment. But then, most people prefer to use social media to engage with the mundane, the personal. In this context, most accusations of social media as being shallow and negative come from the fact that both the public and the private are conflated in the same platform. As I showed elsewhere, in southeast Italy most people have solved this tense situation by finding alternative spaces where they could really be private: such as mobile messaging and WhatsApp.

This points to the second part of my response, which is about the different layers of intimacy people in Grano actually construct by means of social media. I have discussed this elsewhere, but, we can just think of somebody who uses mostly text messages to communicate with her fidanzato, phone calls with her parents, WhatsApp with her best friends, and share Facebook statuses and comments to everybody else. These different layers of intimacy suppose different sets of emotions that could be better expressed by different media. The mechanism by which people use different media to objectify the particular kinds of relations they have or want has been described in the theory of Polymedia.

Therefore, I suggest that most of the stereotypical allegations around social media are informed by a stereotypical understanding of media as a homogenous and consistent environment with well-defined purposes. And it is also true that most people I worked with see Facebook as imposed from the exterior, by some higher social and economic forces, and maybe this is why most of them do not see any problem if someday it will simply disappear.

Facebook and the State: propaganda memes in Turkey

By Elisabetta Costa, on 27 February 2015

Propaganda meme that has widely circulated on social media during the protest of March 2014

The academic and journalistic accounts on the political uses of social media have mainly emphasized the practices of activists and dissidents, or alternatively the control and censorship by States, but I believe that one area of research has been largely overlooked: the government’s production and distribution of social media outputs for propaganda purposes.

After having observed the political uses of social media in Mardin for a long time, I was struck by the wide circulation of videos, memes and news supporting the government and the ruling party AKP. Most of this material was produced and originally shared by institutional sources or other informal groups whenever some significant events occurred. For example, in March 2014 anti-government protests erupted all around the country when a 15 years old boy died after having been in a coma for 269 days, the boy had been hit by tear gas while he was going to buy bread during the Gezi Park protest in Istanbul. In March 2014 the social media sphere in Mardin was populated by memes that were reproducing the government discourses and minimising accusations of police brutality. The image posted above is only one example of the several memes of this kind, the caption says: “This is not the way to buy bread/This is.”

The Turkish government’s engagement with social media was also documented by few journalists, and it was reported that in September 2013 the governing AKP party created a team of 6000 social media users to help influence public opinion. However, I have never come across any detailed report or research about this crucial and important topic.

In Mardin the active usage of social media by the government and the ruling party AKP, is also interlinked with State’s control and surveillance, as a consequence of these two factors, government opponents were not very active online. All this leads me to argue that social media in my field-site, far from creating a democratic public space, have rather reproduced and reinforced existing inequalities and exclusions of political and ethnic minorities.

“I’m Feeling …” – Status Messages on Social Media

By Shriram Venkatraman, on 25 February 2015

Photo by Sean MacEntee (Creative Commons)

“Smiling :)”

“Happy !!!!!!!”

“Feeling Sad…”

“Irritated!”

Do the above look like private messages that one sends? More often than not at Panchagrami, they end up as Status messages on Facebook or WhatsApp groups.

Though these messages might authentically represent a person’s state of mind at a given point of time, there is no denying that such status messages receive much more responses (As Likes or Comments on Facebook or as questions on WhatsApp) at a rate faster than other posts. These kinds of messages normally occur with higher frequency among the young people (less than 30 years old) at Panchagrami.

Status messages such as these tend to have a sense of mystery attached to them and would never reveal the whereabouts of the person (home/office/college or at a shopping center – where does he/she post this message from?) or if this message is related to ones personal or professional life or just something they encountered.

For example: A message such as “Pissed Off!” normally tends to have responses that could be put into several categories,

it could be serious —– “Sorry for you…What happened?”

it could be sarcastic —– “Once again?” or “Me Too!”

it could be an advice —- “Take a walk bro…things would be alright”

or offering immediate support —- ” Call me at +9199******08″

or it could be a joke —- “Take a leak” or “Don’t do it on your chair”

and for no reason a message such as this can attract two dozen Likes on Facebook – now this cannot be categorized under anything.

A message such as “I am smiling” can have responses such as

“I know why”

“What’s brewing?”

“Its good to smile. Smile often”

“hmmmm… hmmmm…”

A look at these messages leads one to reason out the ready support system that a person might have, though one cannot deny that there is a

level of performance associated with this as well. However, letting your ready audience know of a state of mind that one is in has its own strong and weak points. While several point out that channeling your frustration with your boss at work onto WhatsApp/Facebook as a status message and attracting a few soothing responses might calm your nerves, several also believe that people tend to overuse this platform for venting out their day to day frustrations, a few even criticize the neediness of the people who post such messages.

However, interviewing college students at Panchagrami revealed that authenticity of such messages in itself needs to be questioned at times.

Observing that such messages now attract a lot more responses, a few use it to their strategic advantage in order to receive more Likes and comments on their profile.

Now…”I’m Amused!”

Password sharing: I get by on QQ with a little help from my friends

By Tom McDonald, on 17 February 2015

Friendship is only a shared password away. (Photo by Athena Lao, CC BY 2.0)

One of the surprising features of my conversations with primary and middle school students in our rural fieldsite in the north of China was the number who said that the pressures of schoolwork meant they didn’t have any time to ‘care for’ (zhaogu) their social media profiles. Many spoke of the importance of needing to ‘invest time’ (touru shijian) and ‘invest money’ (touru qian) in their QQ account or QQ online games in order to achieve high levels or status on these platform.

For this reason, a number of people that I spoke to, particularly middle school students, told me that they would ask their friends to ‘look after’ their account, or various parts of the games that they played.

Having somebody else responsible for looking after one’s QQ account constituted a very significant indicator of trust, and this seemed especially so in the case of school children. A high proportion of middle school students told me they shared their social media passwords with other people, most often their close friends.

Often when I asked middle school students who it was that they shared their QQ password with, a considerable number of male students would use the term ‘senior male fellow student’ (shixiong) which often indicates incredibly close relationships (similar to ‘best buddies’ or ‘best mates’); whereas for female middle school students, it was often the case that they said the person they shared their social media password with was a female best friend (guimi). In both cases, it seemed that if QQ passwords were shared with friends then it was far more likely that these people were of the same gender as the people doing the sharing.

This not only highlights a different attitude towards privacy on social media, but it also speaks to how platforms can be used to cement long-lasting friendships for young people.

Comparative ethnography: Local and global levels

By ucsanha, on 12 February 2015

For the first year of my fieldwork, I lived in Alto Hospicio, Chile, a city considered marginal and home to the working poor (as the US class system would call them). I spent the year chatting with neighbors in my large apartment building, kicking balls back to children playing in the street, shopping at the local markets and grocery stores, buying completo hot dogs from food vendors, walking along the dusty streets, and taking the public bus to and from Iquique. Now, for my last few months of fieldwork, I am living in Iquique, the larger port city, just 10 km down the 600 m high hill that creates a barrier between the two cities.

This project is based on comparative ethnography, but usually this means comparison across continents, hemispheres, and language barriers, at least. Yet, I have learned a great deal from comparing Iquique and Alto Hospicio, even in just one short month. Iquique is more lively, with a US-style shopping mall, many bars and restaurants, more variety in terms of grocery stores, a beach, a casino, and the sort of variety of different jobs and services available in mid-sized cities across the world. By comparison Alto Hospicio seems bare, even barren. There are no billboards there advertising the latest Tommy Hilfiger perfume (available in the TH shop in the tax free import zone of the city). There are no Peruvian-Italian fusion restaurants, or even cuisines like vegetarian, Indian, Mexican, Thai, or Italian alone. There is no theater, no yearly film festival, and—perhaps most disappointing for me last year—bars with happy hour deals on mojitos.

But what I know of Alto Hospicio, is that while there is less investment in infrastructure and commercial activity (or even advertisement), it is still a lively place. Neighbors chat, people take Saturday trips to the beach with their family, and friends gather to pass time or celebrate special occasions. But in many ways the lack of commercial activity gives Alto Hospicio a homogeneity that one does not encounter in Iquique. As I’ve written before, from the very shape of the houses to the clothing people wear, the spectrum of aesthetics is limited. People work in mining, in service industries, or own small businesses such as a corner store. And everyone knows that for “once” (pronounced own-say), the evening tea, the table will be equipped with bread, margarine, sliced cheese, and sandwich meat to accompany the hot tea. And most people seem quite content to share these things in common with their neighbors.

I wrote last month that the acceptance and even pride surrounding normativity is reflected on social media. But in looking at the social media in Iquique this becomes even more apparent. Foreign newspaper and magazine links are much more prominent. People post pictures from events they attended or even displaying the new throw pillows they’ve purchased for their couch, while in Alto Hospicio photos taken inside the home are rarely are intended to demonstrate the interior decoration. And the percentage of funny memes is much much higher in Alto Hospicio.

None of this shocks me. Coming from a middle-class US background, Iquique feels more like home, and Facebook usage from those residing here looks much more like what my friends at home post. But what this reminds me of is the ways that homogeneity may be working as the world becomes more and more connected. Iquique begins to look and feel like the Midwest of North America (well, with the added bonus of a Pacific Ocean beach), while Alto Hospicio remains very locally focused. That is to say, perhaps certain places are more or less likely to be both homogenized by social media, and have that homogeneity reflected on social media, given their figurative proximity to the global centers (in terms of economics, aesthetics, consumption, services, education, and work opportunities). By looking across all 9 sites of the Global Social Media Impact Study, this may become more or less apparent. We may find that those places that remain on the global “periphery” remain peripheral on social media as well. There may only be a 10km highway separating Alto Hospicio from Iquique, but the differences seem continental.

Does Targeted Advertising Work?

By Daniel Miller, on 5 February 2015

Photo by Mike Licht (creative commons)

As Ethan Zuckerman noted in The Atlantic (14/08/2014) even though many groups and initiatives really didn’t want to go down that route, targeted advertising has become the default funding model for the internet, as people failed to find an alternative. A combination of developments such as big data and mining information from sources such as search engines and social network sites means that today it is possible for ads to be honed quite precisely to the interests of individuals as revealed by their online activity.

It is not at all surprising to find that English people who, as many of my blog posts have argued, are hugely concerned with privacy and keeping people away from their homes and intimate worlds, vociferously complain about the development of targeted advertising. The two most commonly quoted examples are Facebook and the supermarket chain Tesco. A typical complaint was ` Google will change your settings on your cursor, so that every time it goes back and tells them what you are using it for. Then they send you certain adverts….If you join Tescos, every time you go through the till it records everything you’ve brought. And suddenly they start sending you vouchers to buy meat… or this persons a drinker. Everything you do.’

In our project we anticipate cultural variation and it was interesting to read an article in the Financial Times recently (28/01/15) that suggested in China customers of WeChat felt personally insulted when they were not included in a targeted advert for BMW. This leaves us with at least two interesting possibilities. The first is that people say they resent the advertising but actually find them convenient and use them, which is why they continue to spread. Alternatively corporations tend to follow technological advances and do this simply `because they can’, even if in actuality these adverts did not in fact work. When I studied businesses (Miller, D. 1997 Capitalism: An Ethnographic Approach) I found that fear of what the competition might do was much more important than evidence for what customers actually do in understanding business practice around advertising. The academic work on the topic is still slight, and it is starting to look like targeted adverts in some combinations might actually be sending people away from companies rather than building their profits (e.g. Goldfarb, A., and C. Tucker. 2011 “Online Display Advertising: Targeting and Obtrusiveness.” Marketing Science 30.3 (2011): 389-404). In the meantime I have been faced with some of the most egregious examples of such advertising through my research with hospice patients. As one put it `I’ve joined the moving-on group now, since I’ve finished treatment, try and move on. Sometimes I get a lot of feeds and it does get a bit much. Don’t want it in your face all the time, keeps coming up, so I had to stop a lot of the feeds, otherwise every other thing was cancer cancer cancer and I’m not moving on. Think I’ll get rid of these off my Facebook.’

Close

Close