Facebook as a window: managing online appearance

By Razvan Nicolescu, on 31 July 2015

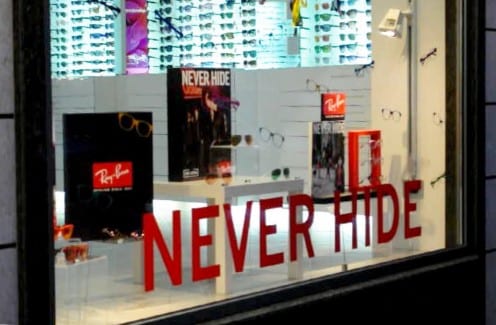

Shop window in Grano (Photograph by Razvan Nicolescu)

A particularly common way that many people in the Italian field site thought about Facebook was by comparing it to a shop window (vetrina in Italian). Some did not exactly like the fact that, like a window, ‘everybody can see your personal stuff.’ In contrast, others used this new kind of visibility as an opportunity to actively promote different aspects of their interests. Out of this latter category, teenagers and some local entrepreneurs were by far the most active in this way, followed by artisans, artists, and a few local politicians.

In my forthcoming book, I explain how much of this region’s history explains why people are very concerned with the way social visibility reflects their social status. For example, families have always demonstrated their core moral values by keeping a clean and tidy house. Equally, most women spend considerable time beautifying themselves, selecting their clothes, making sure their outfits are neat and that their family is equally well dressed before they are willing to leave their own home. Dressing reflects the social and economic status people believe they have, even though their actual economic position could be somewhat different (for example, because of the massive unemployment in the region).

So how is this reflected on Facebook? Just as people put all this time and effort into their offline appearance, now many are extremely careful in curating their Facebook page. They do so by being extremely careful in selecting and editing the photos they upload, showing their support for online friends with comments and ‘Likes’ and in general trying to make sure their appearance on Facebook is consistent with how others would see them ‘offline.’ Facebook is considered a very public platform, and therefore people are very considered in how they post.

Among other things, the role if Facebook here is to actually make sure that there are no major differences between how people appear to others ‘offline’ and ‘online,’ for example, by offering adjustments or justifications when this may seem to some that this is not the case. Recently, a friend of mine in the field site had to post a long message on his own timeline to reply to an accusation from one of his online friends (which remained unnamed) who accused him of not being a proper ecologist. This remark was triggered by some of my friend’s recent postings in which he vaguely displayed some sort of sympathy for mass consumption practices.

Similarly, people are increasing aware that when they dress to go out, some of their friends might take a photo of them and upload it on Facebook. Therefore, that particular photo will have an implication beyond the transience of the particular event they have attended to.

In all these cases, the consequence is that Facebook works as a window that opens up a view both towards an exterior appearance of the individual which also reflects on the social norms existing in the local community, and the interior of moral values or domestic family. For both, people follow clear guides to the type and level of visibility they are expected to reach.

Job opportunity: Can you help the world discover our findings?

By Tom McDonald, on 30 July 2015

Can you help us build our dissemination materials? (Photo by MF)

As part of our project’s ambitious dissemination plans we are currently seeking to recruit a content manager to assist our research team in creating a new website (named ‘Why We Post’), an online course and a series of social media channels to share our research findings with a broad and global audience.

In addition the person holding this post would assist in the organisation of the project including copy editing English, co-ordinating translations, research analysis and in promoting the project to the media and within education.

This is an incredible opportunity to join our team and be part of an exciting project aiming to change the way anthropological research is presented and shared.

Full information on the position is available via the UCL Jobs website. The closing date for applications is 12 August 2015.

Using storytelling to build online courses

By Tom McDonald, on 21 July 2015

The project team filming a video for our online course

Recently we have been filming a new online course on the anthropology of social media that will be available on a major online platform.

Putting together such an online course has been a real challenge. I am sure this would be the case for any such course, however it is especially so in the case of the our own offering, which will draw heavily on this research project.

Our initial attempts made us realise how difficult it is to combine findings from our nine different field sites and nine different researchers into a single coherent experience for learners.

The concept of learning through storytelling has been quite useful in this connection, helping us to think through how the individual points we hope to teach link together and build on each other throughout the course. In turn, this has helped us to decide which bits of our incredible range of discoveries and insights should be included or excluded.

Why do young men from lower socio-economic classes prefer shopping online?

By Shriram Venkatraman, on 3 July 2015

Photo by Shriram Venkatraman

Most of us on social media have noticed the static advertisements that are displayed on the side panels or the advertisements that intrude upon the videos we watch on Youtube. While some choose to ignore them some view them as an irritating factor that impinges on their personal space/time, and while some see them as distracting to say the least, for others they may be informative. The views are as myriad as the advertisements themselves, and are relative to the social context of the viewer.

However, this post is not about the different kinds of advertisements that get displayed on social media, nor is it about any kind of advertising strategy. My aim is simply to illustrate a finding, namely how advertisements on social media can transform the norms of consumption and shopping for the lower socio-economic classes in some societies by acting as a gateway to online shopping.

Let’s explore the case of how advertisements on Facebook have driven young men from the lower socio- economic classes in Panchagrami, South India, to explore the world of online shopping, and thus escape from subtle discrimination and embarrassment they sometimes face in shopping malls.

The young men of lower socio-economic classes in my field site have a fascination with online shopping. Though, most of them are school dropouts, one investment in particular that appeals to them is a smart phone with a 3G data pack. Access to Facebook or WhatsApp isn’t too far for these youth, as this becomes a natural extension of a 3G connection.

Other than socializing on Facebook, another significant aspect of their activity on Facebook is clicking on the different advertisements, specifically those which display colourful clothes, shoes or hi-tech phones. While at the beginning most did not know how to buy from these e-shopping sites, they didn’t have to look far to find informal tutors to advise them. Most of these tutors were educated IT employees who hailed from the same area and were childhood friends of theirs.

While it may seem as though their shopping on these portals is just a natural extension of them being on the internet or on social media, this turn to online shopping has much deeper facets that require attention.

Why Online Shopping?

While most online shopping still requires plastic money (credit/debit card), the Indian e-shopping portals offer a cash payment model known as ‘cash on delivery’ which perfectly fits the cash economy that dominates this demographic. They don’t have credit cards and some don’t even have a bank account. This model lets them choose and buy products online, then pay in cash only when they receive the products at their doorstep. This service gives them access to things from t-shirts to trousers to slippers etc. through these portals, without the hassle of owning a credit card.

Using e-shopping portals gives them an opportunity to experience better service and feel important. This was of particular importance because of the way they were treated by salesmen in malls who would look down at them when they asked too many questions, or if they asked for choices before they had made a selection. They also felt that, because of their skin colour, salesmen assumed that they could use their power and expertise to force products that they would never have chosen.

They very often said that they felt helpless and like fools when they walked out of a store. They also often felt too intimidated and embarrassed to visit upscale showrooms, and often felt out of place. The salesmen often just assumed that they weren’t worth his or her time because they didn’t see them as a potential sale. So, when they would ask questions, the salesman would obfuscate rather than waste their time.

However, this didn’t happen on e-shopping portals. It patiently showcased anything they wanted or even aspired for. Even though they had enough cash, a salesman always got irritated with them, but e-shopping portals didn’t.

Further, anything you asked for came to your doorstep rather than having to go out looking for it. In addition to convenience, this service has allowed them to showcase their power and status in ways that they previously could not.

The availability of cheaper products on these portals also allows them to consume products specifically intending to give them as gifts to their kins. This gift giving through buying things online automatically builds status among their social circles as well.

However, when it came to buying electronics, like smart phones, they preferred a showroom environment so that they could feel the phone before investing in it. They still used the e-shopping portals to compare models, before going to a showroom. Let’s suppose they want a Sony or HTC phone, first they go to the e-shopping portal and compare the visual features, then ask their IT friends to help them with the features, then they compare prices and look for other models and the associated visuals and features, then, finally, go to Youtube to watch videos of how the phone works. They go back to evaluate the number of stars (gold stars) the phone has received on the e-shopping portal. Finally, they decide on the model they want and go to a showroom in Chennai to get the phone.

Given that they are now equipped with knowledge regarding their intended product for purchase, they are more confident when it comes to shopping in mall showrooms and don’t feel intimidated with either the ambience or the salesmen. They often felt that they knew more than the salesmen after this process of acquiring knowledge about the phone through social media.

In other words the collective social knowledge that social media offers, transforms their shopping experience itself, from just being a passive buyer to an assertive consumer, who wouldn’t be put down so easily.

Such experiences have led them to click on more advertisements, as they realize that it was these advertisements that actually offered them a window to a new shopping experience.

Learning to write English

By Daniel Miller, on 30 June 2015

Image courtesy of Sharon and Nikki McCutcheon (Creative Commons)

Our research team is made up of nine anthropologists, of whom less than half are native English speakers (two from England and one from the US), so one might not be blamed for imagining that the problem suggested by the title of this post relates to the other six researchers. Actually this is not the case. In fact this is an issue which relates to each and every member of the research team.

The problem is this – we are currently filming our MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) and creating the website for Why We Post which is the title we will use for publishing our research results. These are intended for audiences, very few of whom we anticipate will be anthropologists. Therefore we want to ensure that all our findings are accessible to people who are, by any definition, not academic. This means that the language must be entirely colloquial and in the form of everyday speech. When you are trained as an academic, it is very hard to refrain from using words in a manner that takes meaning from one’s own academic experience. It is not just that we need to avoid words that were invented as jargon, such as positionality and precarity, but also terms that are used in everyday speech but take on new forms of meaning in an academic context, such as subaltern or even critical.

I actually don’t think I am able to write anymore (though I find I can speak) with this kind of English that everyone outside of academia uses pretty much all the time. Something about the act of writing automatically shifts my use of words back into academic usage. So we have decided to employ Laura Pountney, who recently wrote the text book on anthropology for schools and specialises in explaining anthropology for English school children and and further education as well as writing textbooks on sociology level, to go through all our written texts and check them for accessibility.

I don’t believe this constitutes `dumbing down.’ After all, novelists often express complex and profound discussion and dilemmas using ordinary English to great effect, so we ought to be able to do the same thing. It is possible we have swung the pendulum too far. I noticed that we had a script which translated homogeneity and heterogeneity as sameness and difference, these are colloquial words and could get tedious for educated readers.

On the other hand, all of the text used on these sites will be translated into six languages. This is despite the fact that many of the audiences we hope to reach also use English as a second language, such as regions of India and Africa. From the beginning of the project, our commitment has been to have our findings fully accessible to the people in the regions where we conducted fieldwork. I have felt for some years that the debate on Open Access is partial if the focus is only on cost rather than genuine accessibility to people who, so far, we have excluded through the use of intimidating and obfuscating language. So perhaps we should aim to err on the side of greater accessibility. Having said this, the issue really is very much about trying to strike a balance.

Fortunately, I think the actual material we are presenting is fascinating and whatever is lost by simplifying language will be gained by the richness of what is being described. Since I am also starting to receive requests from schools to speak, for example about the work I did on social media and school banter, this is also a skill I think I need to develop and is perhaps something that all anthropologists should be encouraged to develop, especially the ones who assume, like myself, that we already know English.

Personal and public aesthetics: What I learned from my own visceral reactions in the field

By ucsanha, on 25 June 2015

Photo by Nell Hayes

At first, I couldn’t quite put my finger on it, but over the first several months in my fieldsite in northern Chile I began to realize that one of the reasons I never quite felt totally at home was that the aesthetics of the place never quite fit with my own sense of aesthetics. By aesthetics, I mean the effort and thought that people put into the way things look. In my fieldsite, a city of 100,000 inhabitants, I noticed this in public parks and municipal buildings, in both the inside and outside of homes, and in the way people dressed. It was not only an intellectual exercise, but a visceral feeling. If I wore the clothes that I was used to wearing, perhaps a dress or a fitted button down shirt, I felt as if everyone was staring at me because I was dressed with too much care. Perhaps they were right. There wasn’t really anywhere to go looking smart. The only bar in the city had cement floors, cinderblock walls, and heavy metal bands playing live every weekend.

Over time I thought more about the sense of aesthetics in Alto Hospicio, and realized that while I had considered it entirely utilitarian at first, there was something more particular about it. The aesthetic was very much a part of the accessibility and normativity that prevailed in the city. The predominant aesthetic was not nonexistent, nor did it always privilege form above function or the “choice of the necessary” as Bourdieu calls the working class aesthetic. While many people clearly could afford to redecorate their homes or buy expensive clothing from the department stores in the nearby port city, their aesthetic choices leaned toward an appearance that was not too assuming. They didn’t flaunt or show off in any way. It was an aesthetic that was presented as if it were not one, because aspiring to a particular aesthetic would be performing something; a certain kind of pretension. Yet the aesthetic relies on deliberate choices to not be pretentious or striking; to be modest; to be unassuming. This aesthetic then not only predominated in the material world, but also online. Unlike in Brazil, where young people would never post a selfie in front of an unfinished wall, this was precisely the type of place youth in northern Chile might pose. While in Brazil this would associate the person with backwardness that contradicts the type of upward mobility they hope to present, in northern Chile this type of backdrop would add a sense of authenticity to the person and their unassuming lifestyle.

So, in the end, what began as a visceral feeling of discomfort in the field site, actually led to a very important insight. As I told academic friends many times during my fieldwork, “This place is a great site for research, but not at all a great site for living.” Fortunately, even some of the “not at all great” parts of about living in northern Chile helped my research more than I realized at first.

Reference

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Richard Nice, trans. New York: Routledge (1984), pp 41, 372, 376.

It’s not just about Chinese migrant workers

By Xin Yuan Wang, on 22 June 2015

Chinese female migrant workers working in a local reflective vest workshop. Photo by Xinyuan Wang

A question always strikes me as I write up ethnography and prepare for talks based on my 15 months of fieldwork among Chinese factory workers in southeastern China: what will people learn from Chinese migrant workers’ use of social media? Of course these stories may sound ‘exotic’, but I will see it as a total failure if they are nothing more than novel and exotic in peoples’ eyes.

Ethnography in a way is a storytelling of others’ lives. This technique is also widely used in novel writing, film making, and all forms of the narrative of ‘otherness’. Recently a film came out called Still Alice, a touching film telling the story of an extremely intelligent female linguistic, Alice, in her 50s who suffers from Alzheimer’s. In the film Alice is not only gradually losing all of the professional knowledge she acquired after many years of education and research, but also all the memories of her life, of being a mother, a wife, a woman, even a human being. My colleagues and friends who watched the film shared the same thought, how lucky we are to still have those memories which, from time to time, we take for granted. And some of them, including myself, even became a bit panicked when we would forget something all of the sudden – OMG, is that an early sign of Alzheimer’s?! Whether being grateful, thoughtful, or even panicked, all of these reactions come from the fact that we are placing ourselves in the story and imagining ourselves living her life. Empathy is the word we use to describe these experiences that bridge other’s stories and our own.

And ‘empathy’ is key for the ethnographer. I still recall the days when I felt desperate about the state of my filedwork, that I had nothing to do but watch ‘stupid’ videos on people’s smartphones with the factory workers or just stare at people’s repetitive movements on the assembly line for hours. All the boredom drove me bananas and I howled to Danny that I couldn’t bear such a dreadful life anymore. What Danny said not only calmed me down but also woke me up: “Don’t forget, if you have enough, you can easily walk out in the near future, but for them, it’s their whole life.”

The most unforgettable thing I learned from my fieldwork was not the material I took away for my research, but the personal experience of being able to live those migrant workers’ lives. Through this experience I developed an empathetic respect for other people’s lives and motivations which, in turn, has allowed me to reflect upon, and be grateful for, my own life. However, not everybody has the ‘luxury’ to experience others’ lives like ethnographers do. This further highlights the importance of our research, that we have the opportunity to bring an empathetic understanding of ‘others’ to the public when they read or listen to our research.

People constantly gain knowledge of themselves through understanding others: how we are different from the others, how we are similar to the others, why we are different or similar, these inquiries help us to depict the outline of the ‘self’. This is the main reason for the importance of learning other’s stories, because they allow us to gain perspective on our own lives, to think and feel differently. A good novel or a good film achieves this, so why not ethnography? One could argue that ethnography can do this even better, given its holistic knowledge of the given population and society.

The empathy and thought evoked from an anthropological study of ‘others’ can be very powerful, one of the most famous cases comes from Margaret Mead’s fieldwork in Samoa. Mead’s book Coming of Age in Samoa has sparked years of ongoing and intense debate on various issues such as society, community, social norms, and gender. For example, Mead described how gender is constructed by the local community, in this case one totally different from American society, and argued that masculine and feminine characteristics are based mostly on cultural conditioning. This argument actually influenced the 1960s ‘sexual revolution’ when people in the West started to rethink gender.That’s the real strength of ethnography.

This bares a question for all anthropologists, in what way is your research relevant to an audience who may not necessarily be interested in the specific group or society that is the focus of your research? The knowledge drawn from fieldwork should not be parochial. As we can see in Mead’s case, ethnography about a group of people which seems to bear very limited relevance to people in the West is capable of inspiring people by evoking reflection of the ‘self’, culture, and society.

In some of my talks, as well as at the end of the ethnography I am writing, I always try to remind people that it is not just about Chinese rural migrants. Yes, they are the human faces behind ‘Made in China’, they are said to be part of the biggest migration in human history. However, it is more than that. For example, understanding the ways migrant workers experience social media as the place where real daily life takes place in the context of their appalling offline situation pushes us to think about the complex relationship between online and offline, which is one of the core issues about social media use worldwide. The fantasy images on the social media profiles of Chinese rural migrants may look totally bizarre to you, but the logic of applying imagination to guide, explain, fulfill or strike a balance in daily life is as old as human history – dreams, sexual fantasy, folktale, religion…you name it. So a study of how people play out their fantasies about life with the help of social media and how such experiences impacts people’s lives may not just be relevant in that given population and society. It is not just about Chinese rural migrants, it’s about understanding them as well as gaining understanding of ourselves.

Social media and new rewards in learning

By Elisabetta Costa, on 19 June 2015

Photo by Elisabetta Costa

Education has become an important topic of investigation in our comparative research. Last May we also explored and presented our findings in a workshop held at UCL. In Mardin, similarly to field-sites in rural China and Brazil, parents and kids tend to see social media as a dangerous threat to formal education. The education system in Turkey is built around examination preparation, and examination results can chart the course of a person’s life. In this context social media is deemed by students and parents as responsible for worsening exam results, as it takes time away from books. For this reason students preparing for important examinations often close their Facebook or Twitter accounts for a few weeks or months. Whereas social media seems not to be beneficial to the preparation of multiple choices exams, in other situations it emerged to be quite helpful in the learning process.

This is the case for University students attending the English preparatory class at Mardin Artuklu University. Instructors of English highlighted a general lack of motivation among students, who were more interested in passing the exam than learning the language. Also, students used mnemonic approaches that led them to memorise grammar rules, rather than actively engage with the new language. In this context, social media has contributed to creating new motivations and rewards where the formal education system has failed. Students, indeed, were practicing English on social media in four different ways:

- Male students used Facebook to secretly flirt and communicate with foreign women.

- Students often wrote quotations or uploaded their status in English, they wanted to be seen by teachers, friends and peers as proficient English speakers.

- Students joined English language political groups dealing with the Kurdish issues.

- Students listened to English songs on YouTube.

Love, fame, politics and music became four new rewards which drove students to learn a foreign language. In a formal education system where the main concern of the students is the acquisition of a diploma, social media has created new rewards that positively influence learning motivations.

How did we choose our field sites?

By Tom McDonald, on 18 June 2015

Our project field site locations

A question we are often asked is how we selected our field sites for the project. Why these nine sites? Why are there no sites from Africa, or the ex-Soviet block or South East Asia?

We call this a global study, meaning that we include sites from all around the world, but clearly that does not mean it is a comprehensive study.

There was an initial desire to include the biggest populations and emergent economies such as Brazil, China and India. We never intended to work in North America simply because that area is already hugely overrepresented in the study of social media.

Beyond that, however, much of the selection had to depend on whether there were suitable people available to carry out this research. The initial proposal included a study in Africa but the person designated was not available. We could only employ people trained in anthropology who could also make a commitment to live in these field sites for 15 months and in a very specific timeframe. So logistics was a significant factor in determining the specific nine sites.

Another important factor is funding. Through the generosity of a government-funded research centre in Santiago and the Wenner-Gren foundation, we were able to include two additional team members beyond the original ERC funding, providing the project with one study in Chile and a second study in China.

That being said, this project has always been particularly open and collective in nature. We have gained much from learning about social media use in other parts of the world not covered by our study, and see collaboration as naturally extending beyond our own research team. As part of these efforts, we have also developed a project directory where academic researchers from any institution are able to list their own on-going research on social media in different global contexts.

What’s our conclusion? Introducing ‘scalable sociality’

By Daniel Miller, on 16 June 2015

Scalable Sociality

Right now we are finishing the last of our eleven volumes from this project, a book which will be called How the World Changed Social Media. Not surprisingly, people are starting to ask about our conclusions. There are of course many of these, and the website will also showcase these ‘discoveries’, but as anthropologists our primary concern is to determine the consequences of social media (or what used to be called social networking sites) for our own core concern which is sociality – the study of how people associate with each other.

We have concluded that the key to understanding this question is through what we will call ‘scalable sociality.’ Prior to social media, we mainly had private and public media.

Social networking sites started with platforms such as Friendster, QZone and then Facebook as a kind of broadcasting to a defined group rather than to the general public, in a sense scaling downwards from public broadcast.

By contrast some of the recent social media such as WhatsApp and WeChat are taking private communications such as telephones and messaging services that were mainly one-to-one and scaling upwards. Often these now also form groups, though generally smaller ones. Also these are generally not a single person’s network. All members of the group can post equally to all the others.

If we imagine two parameters – one consisting of the scale from private to public and the other from the smallest group of two up to the biggest group of public broadcast – then as new platforms are continually being invented they encourage the filling of niches and gaps along these two scales. As a result, we can now have greater choice over the degree of privacy or size of group we may wish to communicate with or interact with. This is what we mean by scalable sociality.

However this is just an abstract possibility. What people actually do is always a result of local norms and factors. In each society where we conducted fieldwork, we saw entirely different configurations of these scales as suits that area.

In our South Indian site these mainly reflect traditional groups such as caste and family. In our factory China site an entirely new society of floating workers create largely new norms of group interactivity including their first experience of true privacy. While in our rural Chinese site the main difference is that it is possible to now include strangers on the one hand and to extend various social ‘circles’ on the other. In our English site people specialise in the exact calibration of sociality that is neither too close, nor too distant.

Nonetheless, all of these are variants that can be understood as exploiting this new potential given by social media for an unprecedented scalable sociality.

Close

Close