The town I have called El Mirador is the gateway to one of the most remote regions in Trinidad. Just ten minutes from the town centre, you are surrounded by bush, farming land and fishing villages. Most of the year, it’s a quiet sleepy place. The town is hub; just as many people work outside of the town as the amount of people that work in the town, in local businesses or in the public sector. As an area that developed in the second half of the twentieth century, it also has more of a mixed population than other parts of Trinidad. Like many country towns around the world, normative views are fairly conservative. Political opinion is split fairly equally between the largely East Indian-supported party the UNC and the mostly African-supported party, PNM.

In a usually un-extraordinary place, the town comes alive around events; religious holidays, Christmas and Carnival. Shop fronts transform, local up-market bars and eateries hold themed nights and the World Cup is an additional reason to do what Trinidadians know best: have a good time.

In the first ten days of the World Cup, which ended with a national long weekend of the Corpus Christi and Labour Day public holidays, I watched matches in three family homes, one restaurant and two bars in the town. Facebook is the dominant social media in El Mirador and out of the 250 Facebook friends I have accumulated as part of the Global Social Media Impact Study, 13 posted about the World Cup regularly, as it unfolded. These informants were aged between 17 and 23. For informants in their late 20s and above, the World Cup didn’t seem to impact on how they post. An additional 26 people were tagged in posts and through conversations with informants and, to use the local term: through ‘macoing’ (looking into other people’s business) profiles on Facebook, those tagged watched a game or two in a group with the person who tagged them. I took note of 53 posts and all together, there were more than 100 comments, usually banter, commentary, jokes or discussion, 17 memes and 4 videos. 3 of the local bars I followed advertised World Cup screenings and 3 chain businesses had World Cup promotions.

Advertisements by local bars on Facebook

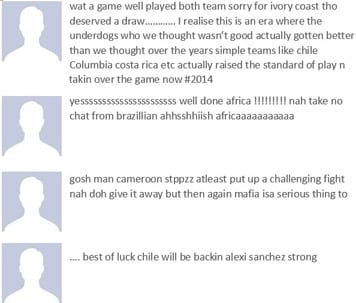

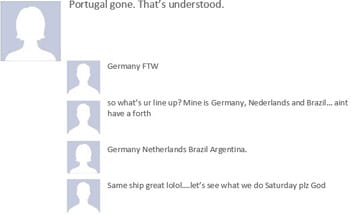

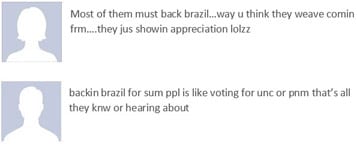

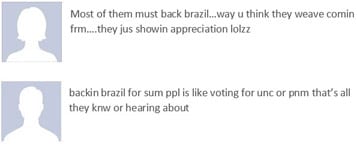

After the first week, commentary died down a little and since Trinidad isn’t competing this year, the favourite teams appear to be Latin American countries (Brazil, Argentina and Chile) and African competitors (Cote D’Ivoire and Cameroon)

Facebook posts supporting South American and African teams

If we follow Tomlinson’s idea that how people view global sports can be better understood if we understand a site’s economic and political dimensions (2006: 2), Trinidad’s history and geographical location can explain the popularity of these teams. There is absolutely no interest or support for the English and US teams but I would only be speculating the reasons why at this point.

When I look closer at the comments and memes, the social media trend in El Mirador in respect to the World Cup becomes clearer, the event is appreciated as a spectacle. The temporary nature of the event attracts attention and fascination, which is probably why even though the competition is getting more intense at it draws towards the finals, the attention on social media is waning. lthough the second week may have just dipped in posts and will increase again towards the finals. How Trinidadians experience temporality and transience has been explored in quite a lot of depth (Birth, 2007, 1999, Miller, 1994) as well as the spectacular, which culminates at the time of Carnival (Ho, 2000). The build up to the event is often enjoyed as much as the event itself, as we see for example with pre-Carnival parties (‘fetes’) which start after Christmas and end the weekend before Carnival Monday. The widest advertising for those is not on mainstream media, but through Facebook events with open invitations.

The nature of posts reflect Trinidadian social life characterised banter and hanging out. The matches are something to comment on and talk about with no particular reason than just to enjoy socialising.

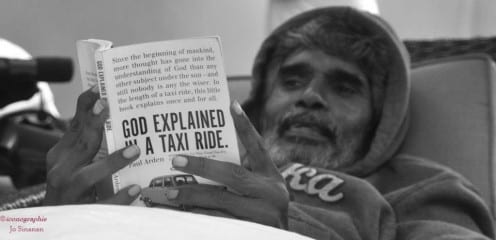

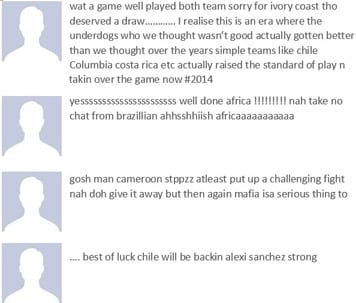

World Cup banter on Facebook

Memes appeal to humour and skill and precision of sportsmanship is appreciated in its moment, as a spectacle.

Some of the funny memes circulated on Facebook

Commentary and posts are funny, good natured or used to start a conversation with others, although there was an odd racially-based or post with more political commentary.

World Cup posts with racial and political humour

Clockwise from top: World cup screening in a local bar, a couple enjoy the game in a restaurant, a proud Messi supporter, an outdoor World Cup ‘lime’, Hindu prayers with a match in the background

On weekends in particular, the ‘lime’ (a Trinidadian term for hanging out) moves from social media and watching matches at home, to watching them with others in their homes or in public bars or restaurants.

In the upcoming weeks we will see if commenting on the World Cup on social media will decline or intensify as the competition heats up. It will then be school holidays and judging from the long weekend where there were less World Cup posts, Trinidadians in El Mirador may leave World Cup sociality on social media to being out more and enjoying the World Cup in the company of others.

References

Birth, Kevin K. Bacchanalian sentiments: Musical experiences and political counterpoints in Trinidad. Duke University Press, 2007.

Birth, Kevin. “Any Time is Trinidad Time”: Social Meanings and Temporal Consciousness. University Press of Florida, 1999.

Ho, Christine GT. “Popular culture and the aesthetization of politics: Hegemonic struggle and postcolonial nationalism in Trinidad carnival.” Transforming Anthropology 9.1 (2000): 3-18.

Miller, Daniel. Modernity, an ethnographic approach. Berg Publishers, 1994.

Tomlinson, Alan, and Christopher Young, eds. National identity and global sports events: Culture, politics, and spectacle in the Olympics and the football World Cup. SUNY Press, 2006.

THE WORLD CUP ON SOCIAL MEDIA WORLDWIDE

This article is part of a special series of blog posts profiling how social media is affecting how ordinary people from communities across the planet experience the 2014 World Cup.

Filed under Culture, Trinidad

Tags: banter, event, Football, lime, memes, nationalism, political commentary, soccer, spectacle, temporality, time, World Cup

3 Comments »

Close

Close