Cricket, cinema, politics and religion are things that interest Tamils the most. This is not only reflected in their offline lives but can be witnessed online too, especially on Facebook. Now, where does football fit into all of this? Though football isn’t something that is entirely ignored, it really doesn’t scale up as cricket does. It is one game which is constantly encouraged in schools during the physical training hours next to cricket, but, it really doesn’t have the same following as cricket does. However, it is nonetheless more popular than hockey, which is India’s national sport.

Most men would tell you that they were exposed to football during their school days, but, as a sport the interest in it gets restricted to their school/college days, compared to their interest in cricket which is carried on to their adult life. However, the scenario is not all bad as there are people who do follow football feverishly and know each team’s statistics by heart, but, the numbers just don’t match cricket. Chennai, the nearest city to my fieldsite – Panchagrami – has a Manchester United clothing shop in a famous mall and people do shop there, some for its brand value and a few as fans.

The Ground Reality

So, how does the recent FIFA World Cup 2014, score in this scenario? While Brazil wakes up to football, it’s almost bed time in India. The live telecast of the World Cup starts only at around 9:30 PM which is almost past dinner time for most folks in Tamil Nadu, India. The first match at 9:30 PM isn’t too tough to follow, but the next slot is close to midnight and the slots thereafter most often takes a toll on people who work. They go back to work like zombies if they stay awake watching the entire series the night before. So, people following the live action of every single match is rare.

These night slots come at a disadvantage not only to fans but also to the hospitality industry. Star hotels, restaurants and bars do play the matches live, but most have a time constraint and normally don’t go over midnight. Though replays of matches do take place in the afternoon, football isn’t really treated as a great marketing option during weekdays, though weekends are slightly different. There is only one five-star hotel in Chennai which has taken football to be a serious way of marketing and attracting fans to dine in and has activities related to the sport 24/7. While a few others do consider this an attractive marketing option, most places haven’t really bothered too much with the idea. Bars and restaurants in Chennai (specifically those in star-rated hotels) play football on their television sets, however, most go on only till about midnight and close down, so catching the live telecast from Brazil in public places is difficult for most people here.

The other issue is with the concept of bars in Tamil Nadu. The bars here are of two different kinds, the first type is attached to the local government-run alcohol shops called TASMAC. But, most middle class men prefer not to frequent this bar and opt to take alcohol home. Further, there isn’t any facility here to watch football. The second kind of bars are those that are mostly present in star-rated hotels or exclusive bars/restaurants and can be pretty costly compared to the local government-owned alcohol shops. So, people frequenting them would normally be people travelling on business or upper middle class/rich folks. However, irrespective of the bar one frequents, if one decides to drive back home, with the stiffening of rules against drunk-driving, one is almost certain to get caught by the law and shell out loads of money (either as a fine or at least in terms of corruption to avoid a fine). Some clubs do offer football viewing during dinner for its members, while most often the television sets in gymnasiums play them as an option along with cinema songs.

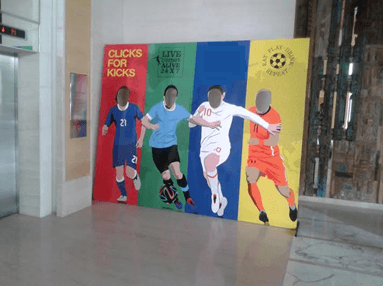

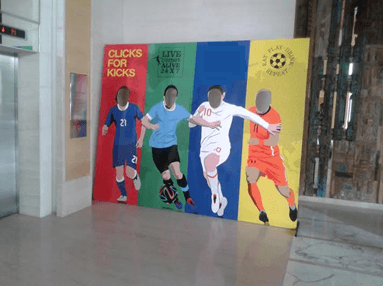

A World Cup 2014 arrangement at a star-rated hotel in Chennai:

The scenario in coffee shops is not too different. Though some do have replays of football matches instead of cinema songs, most prefer cinema songs to match replays. Most often one can catch some advertisement/sign or symbol related to the World Cup in the form of a commercial product. Coffee shops don’t spend money putting together advertisements or banners of the Football World cup, but willingly display beverages bearing the symbols of the World Cup.

For example, Coca Cola cans which have the World Cup advertisement on them.

The constant scene of people who watch windows of shops/showrooms with a television set playing a live stream of the cricket World Cup matches isn’t seen with the FIFA World Cup. Though, the time at which the matches are played might be one reason, the other would be that football just doesn’t interest people here as cricket does. Private viewings in homes do take place in Chennai. However, except for a few nights in the season, most stop watching past midnight during weekdays, due to work day schedules. The only store which has a dedicated football brand Manchester United also only plays matches of the team and not the FIFA World Cup, as a store associate expressed his concern of attracting too much of crowd, if the matches were shown in the store. However, the time of live relay of such matches was also something that did not work out in their favour.

The constant scene of people who watch windows of shops/showrooms with a television set playing a live stream of the cricket World Cup matches isn’t seen with the FIFA World Cup. Though, the time at which the matches are played might be one reason, the other would be that football just doesn’t interest people here as cricket does. Private viewings in homes do take place in Chennai. However, except for a few nights in the season, most stop watching past midnight during weekdays, due to work day schedules. The only store which has a dedicated football brand Manchester United also only plays matches of the team and not the FIFA World Cup, as a store associate expressed his concern of attracting too much of crowd, if the matches were shown in the store. However, the time of live relay of such matches was also something that did not work out in their favour.

One definitely cannot ignore the World Cup as there are vinyl hoardings and the media (print, radio and television) constantly relays news of the World Cup. Most often people seem to prefer watching news slots of the matches or just get the scores from the internet rather than watching it live. Discussions at offices or schools on football aren’t as frequent as they are regarding cricket.

One definitely cannot ignore the World Cup as there are vinyl hoardings and the media (print, radio and television) constantly relays news of the World Cup. Most often people seem to prefer watching news slots of the matches or just get the scores from the internet rather than watching it live. Discussions at offices or schools on football aren’t as frequent as they are regarding cricket.

The World Cup on Tamil Television news

However, it does have its own reflection on social media, and especially on Facebook. Private chats and groups on football do exist. Most often one needs to get invited to these groups, where discussions between Facebook friends happen. Being a part of such a group was clearly enlightening, as it gave the opportunity to witness conversations first hand. Members keep checking for scores online and run their own analysis of teams. They also share links of popular articles related to the teams they love or hate or just about the World Cup itself. Some even run voting options such as the one below

The Scene in Panchagrami

By contrast to the above scene in Chennai, Panchagrami, which lies in the outskirts of Chennai offers a completely different scenario. What hits one is that there are absolutely no vinyl hoardings of football. Further, there are no commercial enterprises that offer an overt advertisement related to football. The only place which has a public viewing of football matches is a star-rated hotel at Panchagrami, situated on a major highway. It offers football match viewing between 7 PM and 11:30 PM every day available only at the roof-top garden restaurant, opened newly at the hotel. However, the screen where the match is projected is pretty small and unclear.

Interviews with the restaurant staff revealed that when families dine in, they really don’t pay too much attention to the matches and most aren’t bothered about them. Some have even requested the staff to change channels (to play cinema songs) as the sport seemed boring to them. However, the staff were ready to admit that excitement picks up only when groups of young men come in to dine and specifically only when they consume alcohol. This normally seems to happen on weekends rather than weekdays. Every evening there are men who travel on business who dine in at the hotel and sit alone to watch the game, just until they finish dinner, most often out of boredom rather than an interest for the sport. The same was true of a coffee shop in the area too; they were content playing cinema songs rather than the World Cup as they felt that cinema songs were much better received by their customers. When probed deeper, they did say that a few customers mostly men, sometimes requested the staff to change channels for a few minutes to update themselves on news related to the football World Cup. Again, timing for catching live action of the World Cup just isn’t suitable for most people nor does it suit the business.

The corner tea shops are normally the spaces where communication of world news is witnessed through informal discussions. Frequenting some of these tea shops revealed that people did speak about cricket in the last week and never once mentioned Football. Informal chats with a few in these tea shops revealed that they just didn’t care about it and were content getting a glimpse of it from the local newspapers.

Most of my informants in the past week were posting pictures of their favourite cricket/cinema stars and political figures. They even Liked pages of their favourite stars, teams or political leaders. I haven’t found even a single posting on football. Even IT workers staying here weren’t really bothered putting up posts on Facebook about football. Interviewing my younger group of informants, revealed a few interesting findings on why they don’t post anything about football.

- None of their friends were interested in it.

- They wouldn’t get as many Likes if they post about football rather than cricket

- It doesn’t allow girls to Like/Comment on their posts – while they did say that the chances of women Liking/Commenting on a post related to cricket was more. In other words, they meant that football was more masculine and could keep away women from actively participating in their profile (through Commenting/Liking).

However, a few did say that they did receive WhatsApp messages from some of their work/college friends about football and most of these friends were from Chennai and some weren’t even native Tamils and hailed from West Bengal or Kerala where football is much more popular. So, while some reeled off statistics they had collected from their office colleagues and from newspapers, they did accept that the discussions on football weren’t as intense as cricket.

The online forums/discussion groups of upper middle class residential apartments also did not have any messages asking for people to join in a public viewing of the sport. However, talking to an International school in the area revealed that they had football coaching sessions over weekends. Attending a few sessions over the last couple of weekends showed that the fathers normally encouraged their sons who were attending coaching sessions to watch World Cup matches. There was a strong family (father-son) bonding that was visible through their discussions on Football on the practise ground. Some were constantly referring to a few You Tube videos of player interviews and techniques. But, other than a few matches they watched during weekends at home or at a Star hotel, most agreed that watching live action of the World Cup just didn’t suit their schedule or timing. However, they did catch up with the scores on the internet.

There were a few men who did agree that they used football as an excuse to go out drinking (alcohol) together as a group. But they just didn’t bother posting about it online, as they didn’t want their wives to know that they were out boozing in the pretext of watching Football.

Most of my male informants did agree that they had played football and liked the game, but it was soon very clear that playing a sport needn’t necessarily transition to following the sport.

Interviewing and constantly checking for updates on Facebook profiles of my informants about their interest in football revealed yet another dimension – women loved cricket more than they did football. None discussed football. Football, they said was very masculine and somehow it just didn’t suit them. However, they did accept that if they had grown up watching football as they did cricket, maybe they would have loved it and changed their favourites. But, it just doesn’t seem to be happening in the near future.

In conclusion, football still hasn’t diffused into the boundaries of Panchagrami as it has in Chennai. As the area transitions, there might be a greater number of Football fans in Panchagrami. Further, the timings do hinder those who might want to give it a try in Panchagrami. As the final match of the World Cup gets closer, maybe people would be much more interested and would start following the World cup. However, at least people catch a glimpse of it in newspapers or on television sets and do update themselves and the situation isn’t as bad as hockey – supposedly India’s national sport – of which people know much less than they know of football.

THE WORLD CUP ON SOCIAL MEDIA WORLDWIDE

This article is part of a special series of blog posts profiling how social media is affecting how ordinary people from communities across the planet experience the 2014 World Cup.

Filed under Anthropology, Business, Culture, Fieldsites, India

Tags: Brazil, Coca Cola, Coffee Shops, Football, India, Manchester United, Panchagrami, star-rated Hotels, World Cup

1 Comment »

Close

Close

The constant scene of people who watch windows of shops/showrooms with a television set playing a live stream of the cricket World Cup matches isn’t seen with the FIFA World Cup. Though, the time at which the matches are played might be one reason, the other would be that football just doesn’t interest people here as cricket does. Private viewings in homes do take place in Chennai. However, except for a few nights in the season, most stop watching past midnight during weekdays, due to work day schedules. The only store which has a dedicated football brand Manchester United also only plays matches of the team and not the FIFA World Cup, as a store associate expressed his concern of attracting too much of crowd, if the matches were shown in the store. However, the time of live relay of such matches was also something that did not work out in their favour.

The constant scene of people who watch windows of shops/showrooms with a television set playing a live stream of the cricket World Cup matches isn’t seen with the FIFA World Cup. Though, the time at which the matches are played might be one reason, the other would be that football just doesn’t interest people here as cricket does. Private viewings in homes do take place in Chennai. However, except for a few nights in the season, most stop watching past midnight during weekdays, due to work day schedules. The only store which has a dedicated football brand Manchester United also only plays matches of the team and not the FIFA World Cup, as a store associate expressed his concern of attracting too much of crowd, if the matches were shown in the store. However, the time of live relay of such matches was also something that did not work out in their favour. One definitely cannot ignore the World Cup as there are vinyl hoardings and the media (print, radio and television) constantly relays news of the World Cup. Most often people seem to prefer watching news slots of the matches or just get the scores from the internet rather than watching it live. Discussions at offices or schools on football aren’t as frequent as they are regarding cricket.

One definitely cannot ignore the World Cup as there are vinyl hoardings and the media (print, radio and television) constantly relays news of the World Cup. Most often people seem to prefer watching news slots of the matches or just get the scores from the internet rather than watching it live. Discussions at offices or schools on football aren’t as frequent as they are regarding cricket.

Apart from this small group of avid fans who are willing to stay up late into the night watching these games, for others only vaguely interested in football, social media becomes a key point through which World Cup information is disseminated nationwide. As mentioned in a previous blogpost,

Apart from this small group of avid fans who are willing to stay up late into the night watching these games, for others only vaguely interested in football, social media becomes a key point through which World Cup information is disseminated nationwide. As mentioned in a previous blogpost,