What’s the benefit of MOOCs?

By Matt Jenner, on 25 March 2014

Many institutions, and countries, the world over have subscribed to MOOC-mania. There are now millions of registered users, thousands of past and upcoming courses all available from hundreds of partners/providers. But why are they all active in this area? An initial motivator for early adopters was to gain momentum from the MOOC-train, it was a way of actively responding to a new ‘game-changer’ in education. The raising of institutional profiles and reputation might have been enough for some to get involved. As the MOOC landscape has become more crowded, pure marketing benefits may be diminishing. There still remains the fact that running a MOOC transpired to be more than a marketing device, instead a range of additional or ‘collateral’ benefits arose for institutions. Luckily this isn’t just for those who were actively creating courses, observers also gained benefits from the presence of MOOCs.

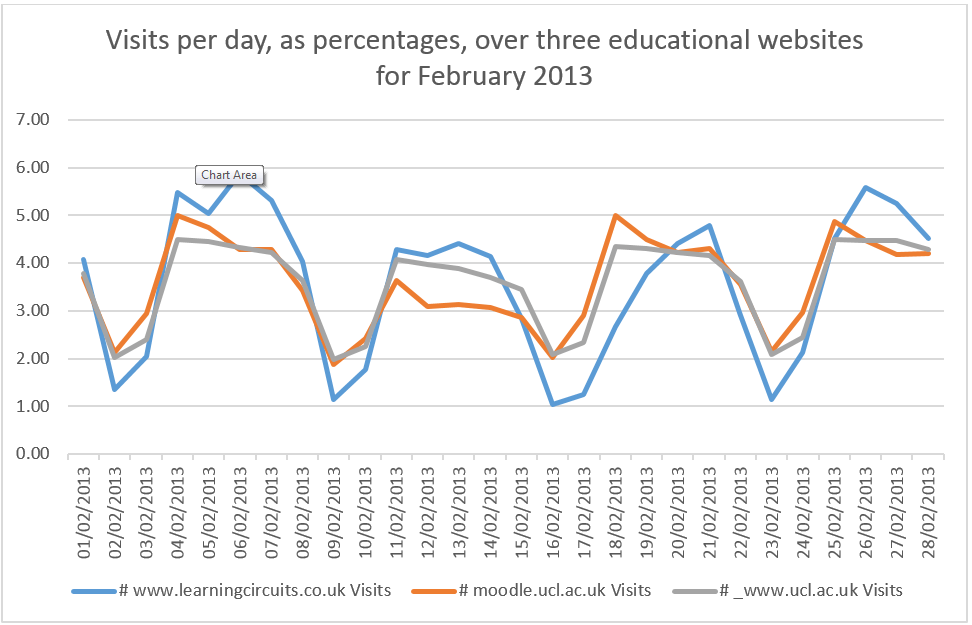

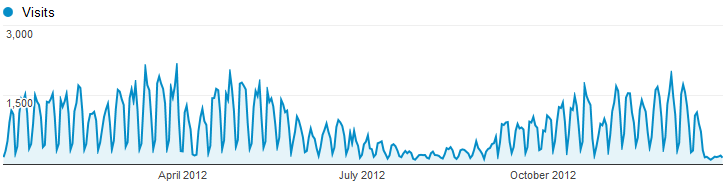

As the very large numbers of learners reported by early US MOOCs are unlikely to be repeated there also seems to be a trend towards more targeting of courses to e.g. specific professional or demographic groups. It’s also possible the traditional delivery format of courses has been undermined with MOOCs, as lurkers are in the majority, perhaps this is a sign of disengagement, or the classic early-warning signal that MOOC providers can read data left by lurkers to create new patterns for access to learning?

Either way, we’ve been keeping up with MOOCs and their associated benefits for institutions who provide them. The table below presents a summary of these benefits from being an active MOOC institution. Data was obtained from top-tier US and European HEIs and we are confident it is not the full picture.

We’ve also broken it into chunks for this blog post:

- Reputation

- Innovation

- Delivery

- Infrastructure

- Student outcomes

And each are provided with a one-liner to give some background or justification for how/why they made it into this selection.

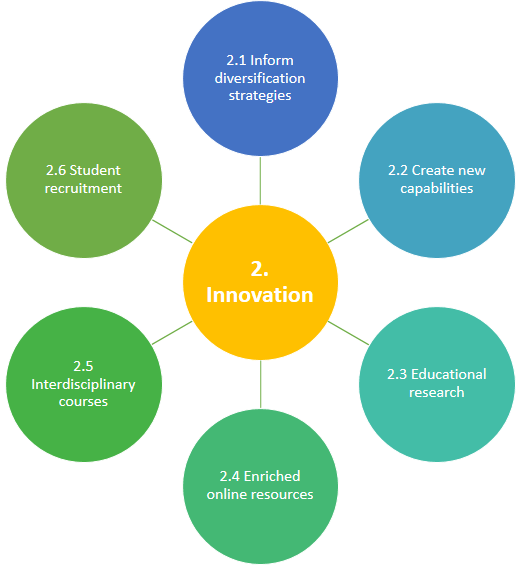

Reputation

1.1 Encouraging engagement

MOOCs don’t just put institution’s names into people’s heads, they actively encourage the staff and students of that institution to interact with the wider public, and visa-versa. Now you could argue the philosophy of a course, and the lack/quality of teacher-learner interaction in some courses but generally speaking, they provide a chance for a learner to engage with that institution/academic/subject/other learners. This is generally considered a good-thing in educational terms, engagement leads to interaction which can lead to some good learning.

1.2 Targeting alumni

Alumni can get involved with MOOCs, be it teaching in a course and leading a group with their experience, or simply remaining in touch with the institution by taking some free courses after they graduate. You could argue it’s a unique hook for some institutions as they may find Alumni contact more enriching if they can offer further opportunities to connect with their prior university via the medium of a MOOC. Those who have completed a MOOC, or ‘MOOC Alum’ may themselves return in the next occurrence to facilitate the course or migrate from Lurker to active learner (or the other way around).

1.3 Outreach

MOOCs provide a chance for institutions to reach out to a wider audience, potentially a group who may never have the chance to link with it in any other form. Disadvantaged groups, or those located half-way around the world are offered a chance, even if thinly veiled, to connect with otherwise unavailable institutions.

1.4 Marketing gains

Obviously this is still an attractive and possible benefit – that hundreds or thousands of people will see your brands and identity. Once registered learners arrive, there’s opportunities to turn them ‘into business’. Not necessarily direct cash, however, which has so far proven to not really materialise from MOOCs.

1.5 Media coverage

The hyped-up tsunami! Oh, the humanity! But really, the media seem to be fixated on MOOCs and have somewhat not really presented a great image of what was happening. Either way, if you’re in MOOC-world you’re likely to get some kind of coverage, ideally international media. There’s a downside; if you mess up, people hear about it. Luckily tomorrow’s hype will override this quite quickly. Call me a cynic if you like but this benefit is low down the list.

1.6 Modern approach

Not every institution in the world has adapted to online learning and many may be slightly behind the technological benchmarks set by others. Many argue that online learning environments such as Moodle are behind the times, or non-intuitive in how they work. Luckily, to some extent, these new platforms and approaches are offering a new lens in which to support education. They come with some teething issues, but these modern approaches are filtering into traditional approaches and hopefully are creating new in-roads in some new areas.

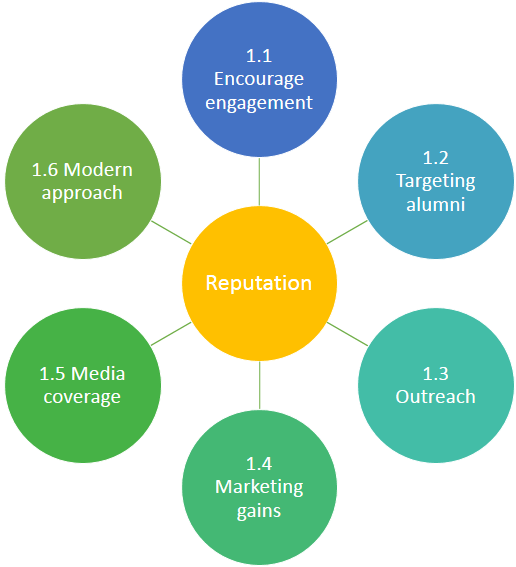

Innovation

Innovation within higher education allows experiments to reverberate back into traditional learning and teaching approaches

2.1 Inform diversification strategies

What? This is all about discovering new ways to do old things. One example is media creation: MOOCs can require a new way to think about an old problem; capture the academic (tip: use a net). Another example is student recruitment, where MOOCs provide a whole new platform for capturing the hearts and minds for potential students. Lastly, they can provide a space to experiment with teaching approaches, for example flipped lectures or the use of OERs. These might all sound normal to you, or implausible – but the general idea is ‘space to play’ and then opportunities to learn, for the institution.

2.2 Create new capabilities

How can you facilitate a discussion forum about learning with tens of thousands of people? We’re slowly working this out now, thanks to MOOCs. Or, how can we create high-quality media while retaining academic autonomy? There are some difficult questions for those who have run MOOCs, but thanks to their experiments, new models are emerging which others can learn from.

2.3 Educational research

This is one of the primary motivators for MOOC-ing for some universities, to create original research into how people learn. Linked to 4.3 – Creating meaning from analytics, this research is uncovering aspects about online learners that might have been harder to measure in smaller numbers.

2.4 Enriched online resources

Making high-quality content for a MOOC means it can be reused for other purposes. Most likely internally, for example raising the offering for blended learning, but also as OERs – where institutions can chose to give all their MOOC content away for free, forever. Creative Commons is playing well here, but some platforms are less friendly about OER. Hopefully time will change on this…

2.5 Interdisciplinary courses

Courses can always break beyond the traditional boundaries, but the level of interdisciplinary MOOCs is quite varied. Firstly students in one institution could use a MOOC as an alternative source of learning (or materials/community engagement). Or, courses themselves can quite openly mix up two subjects without the restrictions of how they may fit into a credit-bearing system of an institution. Lastly a course in one subject, but being open to anyone, may attract others who wish to audit or take part in the course, this mix of people can be a catalyst for some interesting experiments, mixing groups up, or asking for their views from within their own specific contexts.

2.6 Student recruitment

Perhaps not directly, although some have seen direct conversion from MOOC > paid courses they are in the minority. Learners could start using MOOCs as a place to see how that institution really works but we are uncertain they offer a true reflection of learning and teaching from that institution. Can they be used to tempt/lure potential enrolments? Maybe is the closest answer we have right now, but it’s a possible looming benefit.

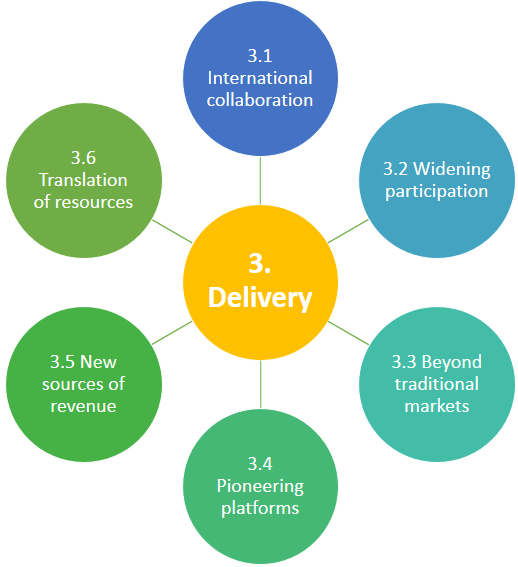

Delivery

3.1 International collaboration

Being online, MOOCs are available to a [mostly] global community. Some have been locked out of a few select countries due to export laws and related issues – but generally speaking MOOCs are international. Moving also into other languages, and not all being English in the first place, means the chances for international collaboration soon come into play. While currently limiting to discussion-heavy courses and some basic wiki’s it’s likely that this area may mature, and take advantage of linking up a large[ish] group of interested learners all in the same environment.

3.2 Widening participation

Not everyone can get into university, many don’t want to and some have too many other pressures (or barriers) to even start the application process. These reasons, among others, can be soothed with MOOCs. By enabling a ‘slide of life’ via the MOOC, they are opening up pockets of institutions to wider audiences. Still a space for growth and a possibility that monetization will be a blockers, but here’s hoping the majority remains open, free and available to the widest group possible. Vocational courses are another bug growth area for some.

3.3 Beyond traditional markets

UCL is a London university with global ambition, but we’re not going to build a campus in every country (probably). We can, however, consider how online environments enable us to expand digitally into new markets. And this isn’t a land grab either, it’s just a phrase that for us means we can connect to people otherwise physically inaccessible. In some areas, this is a huge development and opens doors that could never previously could be unlocked.

3.4 Pioneering platforms

Much like 1.6 Modern Approach – there are providers out there (you know their names) which are adding to the expanding selection of technological platforms for online learning. They all bring innovation to the table and have been built with large capital investments. This is generally a good thing, as their disruption may echo similar innovation in other areas too, i.e. Moodle. They are also looking to solve big issues, such as how do learning environments scale for big numbers of registered users. These technological stand-offs hold back some other platforms, as some are open source, the wider [tech] community may learn a thing or two.

3.5 New sources of revenue

Perhaps not directly as student enrolments, but MOOCs can generate money. The issue now is they tend to cost more to make than they’ll earn back, so it’s not a sustainable financial model right now. Paying a small fee to pass a course may increase in desirability for some, as it offers a chance to do professional or personal development at an otherwise unobtainable/unavailable institution. Many of the big providers recognise that CPD-esk MOOCs (or Small Private Online Courses – SPOCs) are another way to make some moulah. Luckily there are some other benefits to consider as otherwise MOOCs may not be a ‘thing’ already.

3.6 Translation of resource

International reach comes in-hand with multilingual support. One easy way forward for a course which is heavily based on media and peer-led activities is they translate well into other languages. The lack of Professor Famous doing anything hands-on with the learners, means his captures can be converted to another language with only minimal load. However, inter-cultural adaption of translated courses may not be so simple, and there’s a few more things to learn here before all courses are just translated into other languages and assumed they’ll work ‘out of the box’. But progress is being made, and these things shouldn’t just be for English speakers.

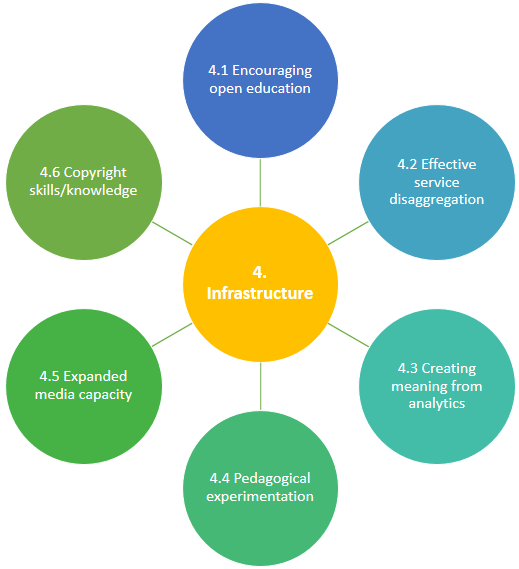

Infrastructure

4.1 Encouraging open education

The best, and most terrifying component – should it all be free and open? Perhaps one day we’ll look back and laugh when institutions were holding their cards close to their chest while others were running ‘Wikipedia-a-thons’ to release as much content as quickly as possible. In the end, it’ll all be out there. But it’s OK because content isn’t king! If it was, institutions would not exist. Education is slowly opening up, one piece of content here, one open course there, a digital learning object somewhere else. Opening up is a strength, it shows character and quality like no other.

4.2 Effective service disaggregation

One of those titles that sounds great, then you forget what it means. In short; the opportunities to unbundle some of the work. Presume you can’t make a MOOC platform, instead of worrying about it, you lean on an existing one. You get benefits too, an established community struggled with ‘that thing’ before you, the registered users flock to see a new upcoming course and the brand can help push you into new domains.

4.3 Creating meaning from analytics

Learning analytics is broadly described as using data collected from learners and using it to better inform their learning experience and/or to improve systems. So far it’s been a nice term, but with a muddy output. Some MOOC platforms have made a conscious effect to integrate the capturing and reporting of data as a priority. This means learner engagement, or activity, can be recorded and used to build models. Linking it to assessments starts to show links between activity and ‘results’. It’s a developing area, and each MOOC learner is a bit of a Guinea Pig running the wheel for a short time.

4.4 Pedagogical experimentation

MOOCs offer a low-ish arena to experiment in. Institutions who have run a few courses have learned a lot about approaches to teaching that can directly inform the next massive course, or bring it back into their traditional teaching. One example is the flipped lecture, which in some institutions is becoming quite normal, but for others it’s a real pedagogical innovation that’s stemmed from MOOCs. My view is these institutions make less use of online learning, and therefore they are leaping forward when going to flipped lectures. Blended learning has been a big offshoot for some US institutions, using their MOOC materials and approaches, back in their credit-bearing teaching.

4.5 Expanded media capacity

Few teaching staff are immediately comfortable with being captured on video, but they are a large component of many MOOCs. Institutions have had a chance to practice creating and presenting media to convey their subject to a wide and diverse group. Additional functionality such as interactive transcripts or playback speed have added further benefits to media delivery on these courses.

4.6 Copyright skills/knowledge

Can you image the shock when that 5 year old PowerPoint with many noncredited images from ‘not sure, Google?’ was not allowed to go online? Open, publicly accessible content is reducing the perhaps flagrant use of other people’s work as masquerading it as one’s own. Another positive tick.

Student outcomes

5.1 Digital literacies

A hot topic on UCL’s agenda, among others, is that of digital literacies – and it’s not just for our learners. The notion that someone, perhaps a young person, is digitally equipped by default is a dangerous and alienating assumption to hold. MOOCs offer a chance for individuals to learn more about the digital form for learning and teaching, it may be becoming more comfortable posting in a discussion forum – or being on live video to a group of thousands of people. Either way, MOOCs may provide some additional benefits for some in this area.

5.2 International experience and globalisation

How does a learner get to understand what the true make-up of the world beholds? Perhaps one answer is to encourage them to interact via a massive online open course. Just open discussion forums alone, wrapped around a particular topic such as Health or Law, could open up new international perspectives for an individual they may have never had before. Potential inter-cultural exchanges could bring real value to such courses, and it’s possible that this remains a growth area for many.

5.3 International communities

Certainly related to 5.2 is the idea of linking up communities from across the globe in the context of a MOOC. There are many types of communities than can spawn from, or join into, a MOOC. Communities of Practice include a collection of people who share a niche interest or professional domain, one that to bring them together physically would be a real challenge. By gathering online, they can share their views on a particular topic and potentially expand their understanding by sharing all they know with others. It could also be more of a social community, where those who share a similar interest can simply join in and be a part of something. Once again, this may be an area of real promise – one to not overlook.

5.4 Mixing internal and external cohorts

How could you get your students to understand the wider issues without bringing it directly to the classroom? One way might be to subscribe them into a MOOC. Previous courses have had their enrolled (credit-bearing) students leading discussions, moderating content, creating learning materials and overseeing MOOCs with thousands of registered learners. This kind of interaction could lead to some progressive pedagogical models of learners teaching learners, creating unique opportunities and developing personal qualities along the way.

5.5 Accreditation and [micro] credentialing

Certificates and badges spring to life in MOOCs. Badges can be awarded for participation and provide a catalyst for further exploration of a theme or learning tool, for example Bronze, Silver and Gold badges for contributions to discussion forums, or marking assignments. They can even be used to ‘gamify’ the learning, used as markers or rewards as the learner’s progress. Certificates are a little more boring, but sometimes people want to have evidence for their learning, and these can do that – they may also make a little money.

5.6 Cross/co-curricular opportunities

Much like 2.5 Interdisciplinary courses – MOOCs provide opportunities for a more casual or flexible approach to learning. One could sign up for a series of MOOCs, pick the bits they like the most and ditch the rest – no-one will question your approach. If anything, platforms will arrive to support it and develop personalised learning journeys for you. This is one example, and as we’re near the end, I presume you get the idea.

Conclusion?

MOOCS are not about making money, getting thousands of learners gawping through your wrought iron gates or dreaming of Professor Famous giving them a high grade. Instead we’ve began to uncover the raft of added value, bonus material or ‘known unknowns’ as some might say. The collective weighing of these should cast a huge shadow of ‘money in = money out’ and instead show that they’re another tool in an expanding and richer toolkit for learning and teaching. It remains a good idea to run a MOOC, or ten, and if you can design your approach to try and benefit from some other bits along the way, then I hope you’ll get a richer and more valued experience from it.

I am also confident we missed a load more out, so if you have some more – or want to argue a point, please go ahead in the comments or on #moocbenefits

Close

Close

Six months ago I blogged about

Six months ago I blogged about