Covid-19: The risk of a double hit to young people’s wellbeing

By IOE Editor, on 23 October 2020

By Dr. Jake Anders

The negative effects of the covid-19 pandemic and its associated restrictions on people’s wellbeing, especially young people’s wellbeing, have been widely highlighted since the onset of lockdowns in March. Unfortunately, there are reasons to believe that even when the direct effects of the pandemic come to an end, there is a continuing risk to young people’s wellbeing from the more long-lived effects of the associated economic downturn that is only just starting.

In a recent research study that John Jerrim, Phil Parker and I carried out, we explored the impact of the last recession (the 2008-09 global financial crisis) on the wellbeing of young people in the Australian context. Our research used data from four different cohorts of their Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth (LSAY), for young people born in 1981, 1984, 1987 and 1990.

Because young people’s wellbeing varies as they age, it’s not as simple as comparing the same cohort of young people’s wellbeing before and after the onset of an economic downturn. The difference that we observe might just be caused by those changes as young people get older. To address this issue, we attempted to isolate the effect of this event by comparing trends in reported wellbeing among overlapping cohorts of young people before, during and after this period. Since young people in these different cohorts experienced this event at different ages, we are able to verify that their wellbeing initially evolved in a similar manner, before comparing what happened as the economic challenge hit.

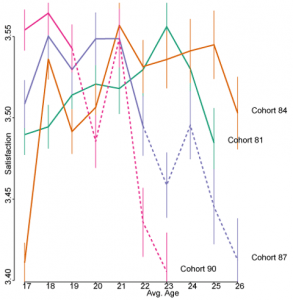

The basic idea of our results is evident from the following graph – although we also applied further statistical modelling to check the robustness of our findings in the paper.

You can follow the average reported level of each cohort’s wellbeing as separate lines reporting annually from when members of the cohort are 17, up to when they are 26. All the lines start out as solid lines – which indicates measures collected before the onset of the economic downturn – before becoming dashed lines after this event.

Because the cohorts were born in different years, the onset of the global financial crisis (and, hence, the change from solid to dashed line in our graph) happens at different ages. Only the cohorts born in 1987 and 1990 experience the onset of the global financial crisis between ages 17 and 26, so only these two lines change to being dashed. The cohorts born in 1981 and 1984 retain a solid line throughout.

The graph suggests that the cohorts born in 1987 and 1990 had similar (or slightly higher) levels of wellbeing as the older cohorts at younger ages. However, a substantial gap emerges between the wellbeing of the earlier and later cohorts, starting at age 19 for the 1990 cohort and age 22 for the 1987 cohort. This indicates that a negative impact on wellbeing was caused by the onset of the global financial crisis.

What are the lessons of this for the current situation? Unfortunately, it suggests that even if negative effects on young people’s wellbeing dissipate when restrictions are eased, the longer-term effects on well-being of the onset of the economic downturn are likely either to prolong these or add to them further. This further increases the importance of policymakers doing all they can to alleviate the negative effects of the pandemic on the economy, and in particular on the challenges that young people now seem likely to face in taking their first steps into the labour market.

The full article on which this blog post is based is freely available online: Parker, P., Jerrim, J., & Anders, J. (2016) What effect did the Global Financial Crisis have upon youth wellbeing? Evidence from four Australian cohorts. Developmental Psychology, 52 (4), 640-651.

Close

Close