Despite numerous campaigns over many years, getting more students to study physics after GCSE remains a huge challenge. The proportion of students in the UK taking physics at A level is noticeably lower than those studying other sciences. This low uptake of physics, particularly by girls, has implications not only for the national economy, but for equity, especially as it can be a valuable route to prestigious, well-paid careers.

The latest research from ASPIRES 2 explores why students do or do not continue with physics by focusing on students who could have chosen physics, but opted for other sciences instead.

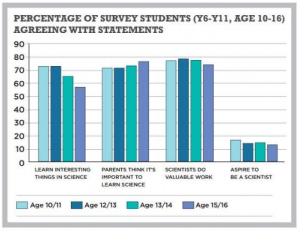

ASPIRES 2 is a 10-year longitudinal study, tracking children’s science and career aspirations from ages 10–19. This briefing focuses on data collected when students were in Year 11 (ages 15/16), a key year for students in England as they make decisions about their next steps, including which subjects to pursue at A level. Over 13,445 Year 11 students were surveyed and we also carried out interviews with a smaller number of students and parents, all previously tracked through ASPIRES.

Students were then classified into those who were planning to study A level physics and those who were intending to study biology and chemistry but not physics.

Who Chooses Physics?

The profiles of the science students who did and did not plan to take physics were very similar, especially in terms of ethnicity, cultural capital, family science background and attainment.

Overall, both groups were more likely to be Asian or Middle Eastern and have higher levels of cultural capital, compared with those not planning to study science. They were also likely to be in the top set for science and have family members working in science.

The biggest difference between the groups was gender. Of the students surveyed who were intending to study A levels, 42% were male and 58% were female. However, among physics students, 65% were male and 35% were female. Put differently, 36% of boys were planning to study A level Physics but only 14% of girls were planning to do so, a highly significant difference.

Reasons for A Level Choices

In both the survey and interviews, students were asked about their reasons for their A level choices.

All A level science students chose usefulness, enjoyment and ‘to help me get into university’ as their top reasons. However, we identified the following key areas of difference:

Physics students were significantly more likely to report enjoyment of physics as a primary reason for choosing the subject, compared to their non-physics counterparts.

Maths and physics – I just chose them cos I enjoy those subjects… Because most sort of degrees or whatever just require maths and physics. (Bob, physics A level student)

- The abstract nature of physics

While both groups of students regarded the subject as abstract (‘things you can’t experience or see’), this abstractness was actually part of the appeal for some physics choosers, whereas it was not so appealing to non-physics students.

With theoretical physics you can go like really complicated and just, like, you know, mind-blowing. (Davina, physics A level student)

Both groups of students were aware of the link between maths and physics but they differed in the extent to which they liked and felt good at maths. 76% of physics students agreed that maths is one of their best subjects, whilst this was the case for only 22% of non-physics students.

73% of non-physics students described the subject as the area of science they found most difficult, compared to 22% of physics students.

Students differed in the extent to which they saw physics as being necessary for future aspirations. For example, 12 of the 13 students interviewed who wanted to study A level physics expressed aspirations that were linked to physics, with over half interested in engineering.

In contrast, 86% of surveyed students who wanted to study biology or chemistry expressed an interest in being a doctor/working in medicine, for which physics was not seen as necessary, as this student elucidated:

Physics isn’t actually quite needed for forensic [science]… but chemistry, biology and English is needed. (Vanessa, non-physics student)

It appears that students wanting to study A level physics find the subject personally relevant to their future careers, rather than just valuable or useful in a broader sense.

For students wanting to study A level physics, high attainment and the ‘hard’, exceptional nature of the subject fitted well with their identity, making them well suited for a subject with a difficult, distinctive (‘mind-blowing’) image.

What Now?

Our findings emphasise just how deep-seated the issue of equitable physics participation is. Simply ‘making physics more interesting’ or emphasising its relevance to everyday life is not enough, especially to increase uptake by students from underrepresented groups.

More work must be done to address the perceptions and choices influenced by the shared image of physics.

We call for the opening up of physics. For example, in the UK, there are disproportionate grade requirements for entry into physics. This restricts who is allowed to choose physics and reinforces the idea of physics as ‘hard’, so students are more likely to see the subject as ‘not for me’.

The syllabus should be re-examined and restructured to be more attainable and relevant for a wider range of students.

We also propose changes to the way science—and physics in particular—is taught in the classroom. Our sister project Enterprising Science has developed the Science Capital Teaching Approach, which aims to make student engagement and participation in science more equitable. This approach includes broadening what is recognised and valued in the science classroom, drawing on students’ own experiences and contributions.

Ultimately, big changes are needed, not tweaks, if we are going to shift the inequitable and declining uptake of physics.

This blog is a summary of the following open access article: DeWitt, J., Archer, L. & Moote. (2018). 15/16-Year-Old Students’ Reasons for Choosing and Not Choosing Physics at A Level. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education. doi: 10.1007/s10763-018-9900-4.

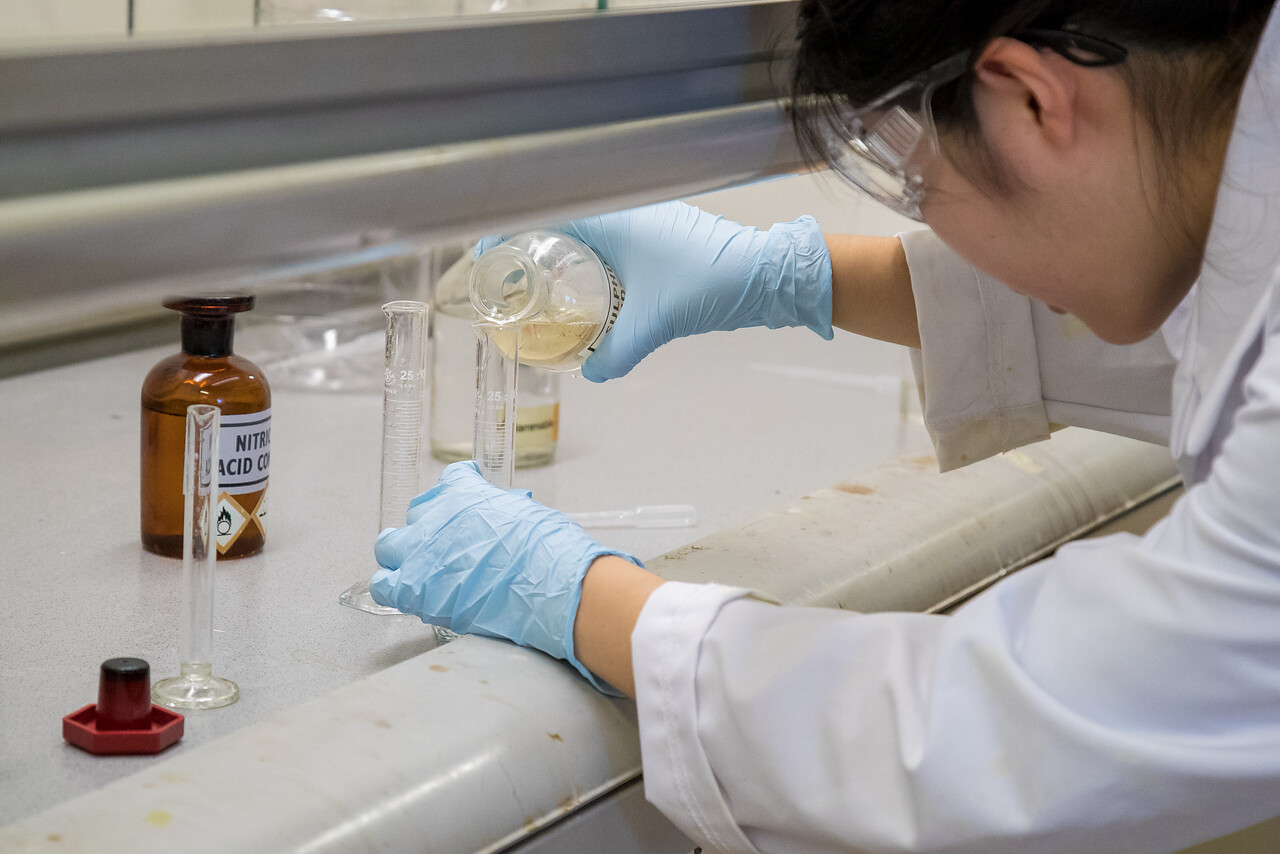

Photo: Mary Hinkley, © UCL digital media

Close

Close