EdTech: Can technology create a better future for education?

By Diana K H Y Lee, on 23 November 2015

Educational institutions are undergoing a deep-rooted reform. The sad truth is, that in modern society, they have a reputation of being a necessary burden; a monolithic industry, slow and difficult to change but absolutely vital for one’s growth and career.

Conversely, technology is now held on a pedestal as the key to innovation and “disruption” of ineffective habits and “enabler” of “viral” growth. I put these words in quotes because they’re used so often now, together with the word “technology”, that they have become buzzwords in our every day lives.

Contemporary technology and applied technology companies are built on this key idea to “Make something people want”, whereas the key foundations of education at university level are being questioned and challenged by advances in our society. This leads to the question:

Can technology create a better future for education? And consequently, is the current offering of educational technology fit for purpose?

Last Tuesday, a live panel debate was held on campus to bring academics, educational technology leaders and students together to discuss this very question. Chaired by Maren Deepwell, Chief Executive of the Association for Learning Technology, the group discussed difficulties faced in currently implemented education technology, previous solutions to some of these problems, and a proposal for action to increase the benefits and impact of educational technology in academia.

Happening now @ucl #UCLEdTech – Is today’s educational technology fit for purpose? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pRxIUEz64tI #edtech pic.twitter.com/9sAgj7kwhj

The debate uncovered some uncomfortable truths, and a wide range of problems that education is facing in general, that educational technology still hasn’t solved. It also (in case you were thinking this is going to be a really grim blog post), uncovered some potentially ingenious solutions, and actionable takeaways that every one of us in the academic community can adopt right now.

The entire debate can be viewed here, so I shall focus on parts of the discussion that stood out (#TL;DW).

The key problems highlighted led to deeper digging by the panel, and here is a rough mapping of the general direction of the discussion, and the main differences, arguments and conclusions:

Technology leaders, students and academics, each had differing views of the purpose of educational technology

Dave White, Head of Technology Enhanced Learning, University of the Arts, rightly established the difference between thinking about teaching as a pure science, and argued, in effect, that it is an art as well:

“For me, teaching isn’t a problem to solve, it’s a practice that we’re constantly negotiating. So sometimes i think the tensions around whether EdTech is fit for purpose or not, is that there are groups of people that will solve or paper over a problem. When in actual fact, teaching and learning is constantly evolving; it’s negotiating, its a discourse. And these two kinds of philosophies don’t necessarily go together.” – Dave White

Current UCL students, Sareh Heidari and Daniel Copleston, expressed the feeling of not being understood or catered to by current educational technology tools (i.e. Moodle), “I’m not quite sure if EdTech knows what its purpose is“. Diana Laurillard, Chair of Learning with Digital Technology at the London Knowledge Lab, UCL Institute of Education stressed the importance of technology and academia coming together to invest in and create the right technological tools for education, a truth that underpinned most of the discussion.

Technology leaders expressed their views on this process of definition with the characteristic problem-solving method: What is the problem? How can we solve it?

- Rajay Naik, CEO of Keypath, essentially stated his company’s mission – “agility, flexibility and plurality of choice for all students wherever they are around the planet“.

- John Baker, CEO of D2L, explained their research-based “mission metrics” in defining what he thought the purpose of EdTech was: University growth, Learning outcomes, Driving better retention / completion / graduation / continuation rates, Student satisfaction, Student engagement, and Productivity / saving time

- Paul Balough, CEO of LearnForward, emphasised the importance of having real-time “NASA-level” technology that doesn’t fail on educators when they most need it as the key purpose of the educational technology they are working on.

I managed to have a chat with the VP of Sales, EMEA of D2L and Paul before the panel started, and we shared the sentiment that although educational technology has done a lot, there is still a long road ahead. This sentiment seemed like one that was shared by the panel and the audience as the debate unfolded, despite championing individual technologies.

“Education is an individual client industry.” – Diana Laurillard, and the Concepts of Collaborative Learning & Teaching

“(cont’d) We are taking individual students to be someone they are not sure even how good they can be, and we have to help them in that process. That’s a difficult thing to do.

So part of what we need to do is to learn from them, and the teaching process is as much a learning process as it is engaging in students and telling them about the big ideas.”

Diana opened the next section of the panel by outlining a huge challenge that educational technology has not solved – the lack of an infrastructure for collaborative learning, because, as she explained in a later part of the discussion “that is what we’re trying to teach our students.“

The question of whether collaboration is actually already happening in the face-to-face context, and the fact that it is not, was rightly pointed out by Dave White. “The higher education sector is not as interested in collaboration as we claim we are… technology is acting as a mirror on how we are.“

He later gave a great example of this, and a hard truth about higher education institutions, during a section of the debate concerning successes in educational technology:

“The biggest success that often we don’t discuss directly is: Because of the web, anybody can publish.

Which is one of the reasons why (publishers’) closed publishing model looks so bizzare. For me, the biggest educational successes are wiki, youtube, blogging, discussion on twitter at the moment, etc.

This is something we need to take advantage of in our institutions, because generally speaking, higher education treats the web as if it was just an inconveniently chaotic library. We need to start saying, ‘Anyone can publish’!” – Dave White

Resistance to new technology & “Is there something profound about education that we’re not driving forward when we’re thinking about technology?” – Rajay Naik

This is very closely related to the previous point, as there was a general admission on the panel that we do have some very good tools, but because they’re not fully maximised, we are unable to grow and “make technology work for us“.

Andrea Sella, Professor of Inorganic Chemistry at UCL, pointed out the importance of the right infrastructure for collaborative teaching. He bravely said that the systems we currently use are “difficult to manage content and deploy it on slightly different contexts.” These hurdles far outweigh the value of teaching to academics in their schedules. He argued that “valuing teaching and learning is something we need to do more of“, using words like “learn-bait” and “stealth methods” to describe the ways he advocates for e-learning with his students and fellow staff.

He and Dave White agreed that it wasn’t just staff, but also students who may not want to learn or may not be comfortable with new technology. As a student at UCL myself, and of Mathematics and Computer Science nonetheless, I see the same system that Andrea talks about and I’m inclined to argue that these are design and UX problems. Let’s face it, Moodle really isn’t that great…

One of my close friends is the President of the Technology Society here at UCL, and he always likes to tell me (especially when designing our website) – “Design (or make/explain) it like I’m 5!”

Is the resistance to new technology due to the poor design of current systems? (e.g. Andrea explained how he had to find out what functionalities Moodle offered on his own because it wasn’t straightforward?) or because of a deeper problem, that the higher education community is not as collaborative as we make it out to be?

One of the technology leaders, John of D2L, also shared an anecdote of a previous success with an educator who used a “research-based methodology” (by “research-based”, he means metrics-driven) to educate her students, keep track of their individual performances, and ultimately fulfil the goal of scaling up whilst maintaining a personal touch to her teaching. Thus proving that maybe it’s the combination of and educators approach to teaching, and well-built technology that enables quality teaching en masse.

The terms interoperability, open-source, and open APIs soon came up, and the techie in me instantly lit up. One of my favourite services, Slack, is precisely my favourite because of its cross-platform capabilities and open APIs. John had mentioned how they designed their LMS (Learning Management System) with accessibility, and equality of access in mind. So after hearing about Brightspace, and seeing this pretty awesome case study and demo of it being used effectively in Singapore Management University – I’m asking myself, “Why do we still use Moodle and Portico?”

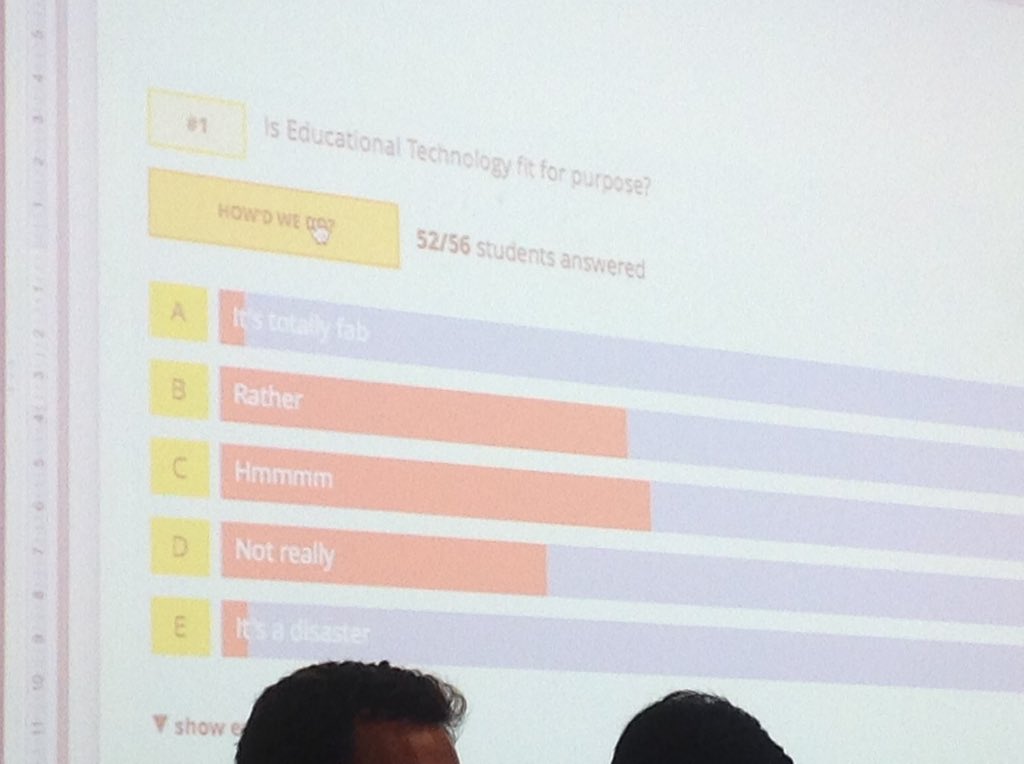

And the result is mmmmm #ucledtech pic.twitter.com/xQ4GlG7Om8

Ultimately, the responsibility comes back to us.

“We have the huge ambition here at UCL to teach our students to become researchers.

This is the key thing, they’ve got to understand what it means to do research. Whatever job they’re going to, they’ve got to understand team working, they’ve got to understand how to work in a professional context where they probably need to learn how to collaborate.

So we’ve got to embrace that in part of the way that we teach.” – Diana Laurillard

The academics concluded that dialogue is needed to produce things that help educators observe and understand how students the way students are thinking, and that funding needs to go into investing in the development and contribution to educational technology by the academic community itself, “It’s got to be up to the academic community to find a way to take this forward.“

Diana also recommended that the world of teaching become more like the “world of scholarship and research“, where “you wouldn’t launch into new innovation without reading what has been done” and we need to “collectively build the knowledge of how to do this.”

“For every pound that is spent on the physical estate, would like to see a certain percentage on digital estate.

If we were to visualise our digital estate in our universities, would they look like the shiny new buildings that our universities are making, or would they look like kind of the ones we would want to forget about?” – Dave White

Students, Sareh and Dan, agreed and wanted to see more engagement between the academic community and EdTech companies, such as short, regular, and productive meetings to take things forward.

EdTech leaders were proactive about the necessity of a better feedback loop; Paul expressed how he “would like to see teachers and professors getting involved in development cycles of software early on, at the very beginning.” Andrea agreed, by concluding that “teachers are just as much learners in this process”, and wanted to be able to “find the time to try things and work with developers.“

The panel was finally concluded with this poignant quote from Diana:

“We must take responsibility for (taking educational technology forward), and who else would we give that responsibility to actually?

As self-respecting academics, I’d jolly well think that we should be owning what it takes to make good use of this technology, and find ways in which every single one in academic profession to make some small contribution to just taking things forward a bit, then infrastructure to share and exchange and build on each others’ work.

As we’ve had for a hundred years in research, why can’t we begin to get that in teaching? And then we might begin to move forward.

The overall consensus was thus that educational technology has had many successes, but it is not where we want or need it to be, yet. All parties involved, academics, technologists and students must play their parts in contributing to the creation of technological tools for our collective goal – “connected, personalised, research-based modes of education.”

As we answered many questions, we uncovered even more. The one that stands out the most is:

It’s not a new idea that education is about teaching a method or style of thinking. Can technology change or enable that in a scalable way?

Perhaps this is one to discover the answers to at #LearnHack, the “hackathon to revolutionise learning at UCL”.

Close

Close