Cavendish Square 5: the Duke of Cumberland’s statue

By the Survey of London, on 19 August 2016

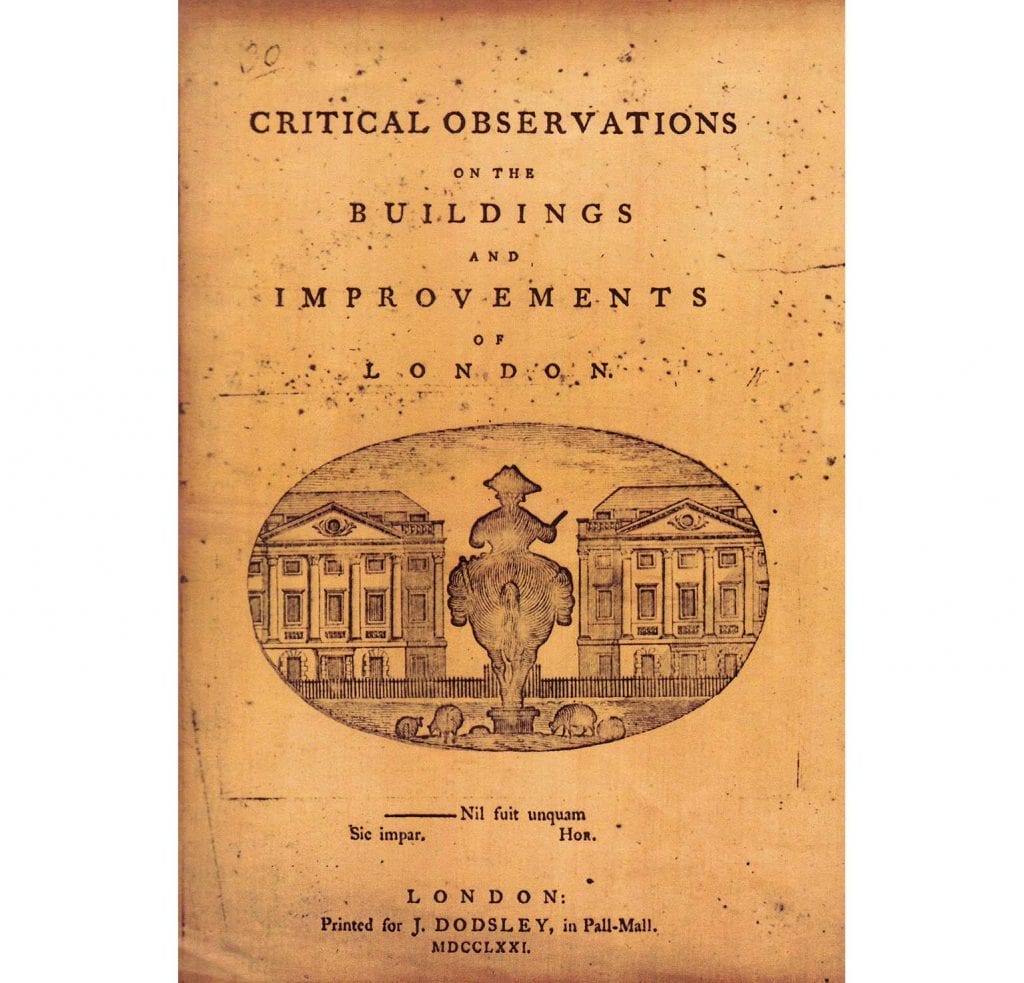

This is the fifth instalment in an occasional series of posts about Cavendish Square. John Stewart’s Critical Observations on the Buildings and Improvements of London (1771) said of Cavendish Square that ‘the apparent intention here was to excite pastoral ideas in the mind; and this is endeavoured to be effected by cooping up a few frightened sheep within a wooden pailing; which, were it not for their sooty fleeces and meagre carcases, would be more apt to give the idea of a butcher’s pen’. This was a satirical allusion to the square’s new statue of the Duke of Cumberland, the ‘Butcher of Culloden’, commander at that final and decisive defeat of the Jacobite rising in 1746. All the same, the square was indeed let to a butcher for grazing.

John Stewart’s Critical Observations, 1771.

The gilt lead equestrian statue of the Duke of Cumberland had been erected in 1770 at the cost of Lt. Gen. William Strode, who had fought under and befriended the Duke, and whose own memorial in Westminster Abbey records him as ‘a strenuous assertor of Civil and Religious Liberty’. At the time Strode lived on Harley Street, on the north-east corner with Queen Anne Street. The Duke’s sister Amelia, who had paid for a lead statue of George III for Berkeley Square in 1766, lived at the west end of the north side of Cavendish Square. Strode conceived what was London’s first outdoor statue of a soldier in 1769, the same year he was alleged to have withheld clothing from his soldiers, a charge of which he was acquitted at a court martial in 1772.

J. P. Malcolm’s engraving of 1808 (© City of Westminster Archives Centre).

The statue was by John Cheere, who had made another version of Cumberland for Dublin in 1746. The paunchy figure in modern dress faced north to the contemporary temple fronts of what are now 11–14 Cavendish Square (see earlier post). That the statue faced this way, presenting its rear to those who approached the square along the Hanover Square axis, may reflect where Princess Amelia and Strode lived. It also looked to Scotland. The statue was immediately ridiculed on aesthetic grounds; any politics in the gesture appear to have passed without published comment.

Meekyoung Shin’s soap statue, photographed in 2013.

Lacking admirers, the statue fell into dilapidation. In 1868 the 5th Duke of Portland took it down, ostensibly to be recast. It never was, perhaps simply melted down instead. Its Portland stone plinth survived, with Strode’s inscribed dedication. By 1916 this had been encircled by a roof on thin columns to create a summer house. That lasted into the 1970s.

Meekyoung Shin’s soap statue in 2014 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave).

In 2012 a replica of the lost statue was mounted on the plinth, made of soap on a steel armature by the Korean artist Meekyoung Shin as Written in Soap: A Plinth Project. She anticipated its gradual and scented erosion within a year, but its tenure was extended, her commentary on mutable monumentality complicated by endurance and popularity. An identical replica was installed at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Gwacheon, South Korea, in July 2013. The Cavendish Square statue was dismantled in 2016.

Meekyoung Shin’s soap statue in 2015 (above and below).

Close

Close