The Davenant Centre, 179–181 Whitechapel Road: part one

By the Survey of London, on 2 March 2018

An undemonstrative road-side building of 1818 and a showy but concealed rear addition of 1895 are all that is left standing in Whitechapel to represent a significant educational history. This spans more than three centuries and a site that extended from Whitechapel Road to Davenant Street and Old Montague Street. Until 2017 this history was sustained by a youth centre that perpetuated the name Davenant. Its closure in 2017 leaves the future of the two listed buildings uncertain. The history of the Davenant School in Whitechapel will be presented here in a two-part blog post.

First Davenant School

Ralph Davenant was the Rector of Whitechapel from 1668 who oversaw the rebuilding of the parish church of St Mary Matfelon in the 1670s. He was a fellow of Trinity Hall, Cambridge, and a descendant of Bishop John Davenant, a moderate Calvinist who had represented the English church at the synod of Dort in 1618; he was also a cousin to the historian Thomas Fuller. Planning for a school for the poor children of Whitechapel began in earnest in 1680, possibly following up an idea conceived by Davenant’s predecessor and father-in-law John Johnson. Johnson’s daughters, Mary Davenant (Ralph’s wife) and Sarah Gullifer, endowed two of three shares of an estate in Essex (Sandon, near Great Baddow) to be overseen by a newly formed body of trustees to maintain the school. When Davenant died in 1681 his will directed that £200 he was owed go directly to the building of the school, and that his goods be sold after his wife’s death to raise money to see the plan through.

Mary Davenant lived on and the trustees struggled at first to find a site. However, the easterly stretches of Whitechapel Road were not fully built up in the 1680s and the parish held a large plot on the north side to the east of present-day Davenant Street for almshouses and a burial ground. The easternmost part of this land, a frontage of 50ft, was given up for the school in 1686 and building work ensued. Endowments proved insufficient and in 1701 an anonymous benefactor gave £1000 to clothe as well as educate the children at the ‘School House of Whitechappel Town’s End’. In 1705 the Rev. Richard Welton invested this money in Thames-side land at East Tilbury.

The first Davenant School of the 1680s. (From Robert Wilkinson’s Londina Illustrata, 1819)

The school building of the 1680s was a brick range with a seven-bay front, a single full storey with pairs of hipped dormers in a hipped roof flanking a pedimental centrepiece, all set behind a forecourt garden and enclosing brick wall. The main room on the west side was for the teaching of forty boys, that on the east for thirty girls, above were living spaces for the master and mistress. A single central doorway gave on to an open passage through to a garden at the back, the schoolrooms evidently entered from the sides of this passage. An aedicular niche above the main entrance rising up to the open pediment is said to have stood empty until the late eighteenth century, awaiting a figure of Davenant for which funds never stretched. Samuel Hawkins, the school’s Treasurer, then acquired and saw to the painting of a scrapped wooden statue of a figure in clerical dress to make up the deficit. There were further benefactions and by the 1790s the premises, already enlarged westwards after 1767, had been extended at the back.

In early 1806 the Trustees decided to double the number of children and a shed and ‘dust-bin’ behind the school were converted to form an additional schoolroom. Anticipating the increased attendance, one of the Trustees, William Davis (1767–1854), the co-proprietor of a sugarhouse on Rupert Street who was to found the Gower’s Walk ‘school of industry’ in 1807–8, saw to it that the Rev. Andrew Bell was invited to Whitechapel to introduce his monitorial (Madras) system of education which had as yet made limited impact. Bell attended the school daily in September 1806 and with Davis’s fervent support and the employment of a trained assistant (Louis Warren, age 13), and then of a schoolmaster (a Mr Gover), both from Bell’s base in Swanage, they successfully established a showpiece in Whitechapel for wider evangelisation of the benefits of Bell’s monitorial system. This gained influential Anglican support and led in late 1811 to the foundation of the National Society for the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in England and Wales. The episode has caused the Davenant School to be hailed as the cradle of England’s ‘National’ schools.

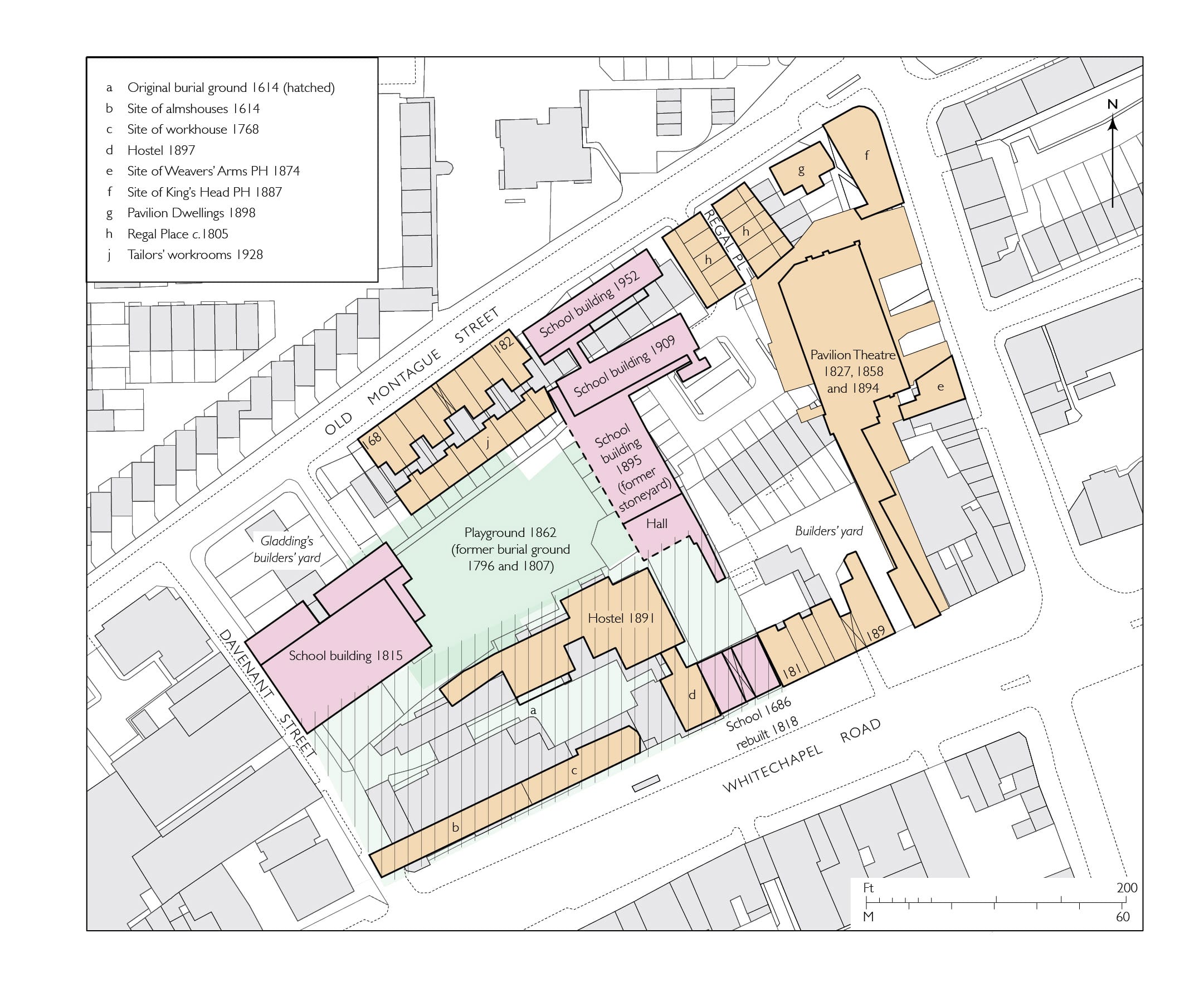

Block plan showing Davenant and related school buildings and principal nearby sites as in 1953 (buildings of 2016 in grey), drawing by Helen Jones for the Survey of London. Please click on the picture for a larger view.

St Mary Street School

There followed in September 1812 the formation of the Whitechapel Society for the Education of the Poor, as a branch of the National Society. Daniel Mathias, Whitechapel’s Rector since 1807, headed this initiative towards educating more of Whitechapel’s poor children. A survey of the parish had uncovered 5,161 children under the age of seven and 3,204 above that age. Of the latter, 991 attended the thirty-two schools already in the parish, leaving 2,213 uneducated. Few parents attended church, providing an additional motive for the evangelical Society. A scheme coalesced for the establishment of a new school with a hall large enough for 1,000 to be taught on Bell’s (National Society) principles; it would also be used for religious service on Sundays. The first thought was to procure an adaptable building, but by early 1813 there were plans to build on land to the north of the 1680s school and a lease was agreed. In the event the Society decided to use this land to extend the parish’s burial ground eastwards and to build the school on the west part of the burial ground to face the recently formed St Mary (now Davenant) Street. The Vestry gave up the land and the Bishop of London approved the project in the summer of 1813. However, funds were wanting; despite a grant of £300 from the National Society, the building fund was more than £1,000 short of its target of £2,500. The Duke of Cambridge laid a foundation stone on 12 October 1813 in an opulent ceremony said to have been attended by thousands; that brought in £677 11 6 in donations. Completed in 1815, the building was among the earliest purpose-built National schools. It was also, as Nikolaus Pevsner had it in an unconscious recognition of the intended secondary use, ‘like a chapel’. [1]

Davenant (formerly St Mary) Street in 1973, showing the National School of 1813-15. (Photograph by Dan Cruickshank at Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives)

Its architect remains unknown, though for circumstantial reasons Samuel Page is a candidate, as will be explained. It was a single-storey stock-brick barn of about 80ft by 120ft. Its round-headed window openings, some very tall, had cast-iron Gothic tracery. There were porches at both ends and a western clock turret. The main square room to the west was for the teaching of 600 boys, with a half-sized room beyond for 400 girls, all convertible into a single space. Two rows of square timber posts helped support a vast queen-post truss timber roof. There was a hot-air heating system, devised and paid for by Davis with John Craven, another Goodman’s Fields sugar-baker. Tom Flood Cutbush (the son-in-law of Luke Flood, see below) procured an organ, which he played himself, also arranging performances of oratorios in the 1820s.

In 1844–5 the Rev. William Weldon Champneys oversaw reconfiguration of the east end, the girls’ room reduced, raised and given a railed balcony to create space below for an infants’ school, with living rooms for the master and mistress. Other subdivision for classrooms in the western corners followed in 1868–9 with G. H. Simmonds as architect.

Ordnance Survey map, 1873, showing the Davenant and St Mary Street schools.

The west porch was lost when St Mary Street was widened in 1881–2. George Lansbury, an alumnus around 1870, recalled ‘what a school-building! No classrooms, one huge room with classes in each corner and one in the middle.’ [2] The east part of the burial ground, disused from 1853, was taken for a playground from 1862. This was shared with the Davenant School as well as the Whitechapel Union, for which a disinfecting house was inserted in the ground’s north-east corner at the south end of Eagle Place in 1871. This workhouse shed gained notoriety as the mortuary to which some of the victims of ‘Jack the Ripper’ were taken in 1888. It was thereafter replaced. The National School was also known as the Whitechapel Society’s School, St Mary’s School or St Mary Street School. In 1874, 360 children were presented for examinations, a decade later 443. It had less cachet than the Davenant School, which, to Lansbury, was for ‘“charity sprats” – girls and boys dressed in ridiculous uniforms’. [3] After administrative changes there were adaptations in 1889–90, including the addition of a caretaker’s house to the north. The school continued under London County Council maintenance as Davenant Elementary Schools, its roll gradually declining from 784 in 1900 to 300 in 1938. It closed in 1939. After post-war use as a second-hand clothing warehouse and despite calls for its preservation, the building was demolished in 1975.

St Mary Street School in course of demolition in 1975. (Photograph by Michael Apted, courtesy of Historic England Archive)

Davenant School rebuilt

Rebuilding of the original schools of the 1680s by the Charity School Trustees followed hard on the heels of the opening of the National School. Larger premises were wanted to accommodate 100 boys and 100 girls, again for the application of Bell’s system. The funding of this project had been given a start by Samuel Hawkins, who had donated £600 in 1808 for building a new school, and a coachbuilder called Lewis (possibly Thomas Lewis, a coach-master of 45 Leman Street), who gave £500 in 1817. Mathias was still the Rector and the Treasurer for the trustees was Luke Flood (1738–1818), a painter, corn chandler and corrupt magistrate and commissioner of sewers who had premises on Whitechapel Road (on the site of No. 57). Flood left £1,000 to the school when he died in February 1818; this was the most munificent of the period’s gifts. Flood’s son-in-law was the architect Samuel Page who had been acting as a surveyor for the parish since at least 1807. Around 1813 Page was also involved in securing an improved endowment for the school. It seems likely that he was charged with designing the school building; it is a characteristically sub-Soanian work. He was probably working with Thomas Barnes, the local bricklayer and house-builder, another trustee and commissioner of sewers who contributed £100 to the fund in 1818. Major Rohde, a Leman Street sugar refiner, was also a trustee. Another was William Davis, who succeeded Flood as Treasurer. The foundation stone was laid in June 1818 by the Duke of York; completion evidently followed quickly.

The Davenant School’s front building of 1818, photographed as the Davenant Centre in 2017, by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

The two-storey and basement five-bay yellow stock-brick building, roughly square on plan, was laid out to align with the workhouse. It originally had steps up to a raised ground floor at its central entrance arch, with a deeper railed area in front of the basement, and a dedicatory stone plaque in a blind arch above the entrance. There was a central staircase and a single classroom to each side on each of the main storeys. In the 1860s, after outbuildings to the west were given up, two blocks were built in the yard for boys, the front range being given over to girls. The plaque had been taken down before major changes in the mid 1890s that were part of a thorough reformation (of which more in the second post). The steps and the staircase were removed with the railings pushed back for a ground floor at pavement level for improved access to new buildings behind – a return to the open passage arrangement of the 1680s. The tympanum of the entrance arch gained a foliate terracotta panel (lost around 1980) and the legend above was changed from DAVENANT-SCHOOL to THE FOUNDATION SCHOOL in 1896, retaining WHITECHAPEL SCHOOL on the central blocking-course parapet above. The schoolrooms were converted in the 1890s to be a chemical laboratory and two workshops, a lecture room, library and dining room, with caretaker’s quarters.

To be continued.

Do you have any memories of the Davenant School? The Survey of London has launched a collaborative website titled ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ and welcomes contributions. Please visit: https://surveyoflondon.org/map/feature/452/detail/#story.

References

1 – Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: London except the Cities of London and Westminster, 1952, p. 426.

2 – As quoted in Roland Reynolds, The History of the Davenant Foundation Grammar School, 1966, p.51.

3 – Ibid.

Close

Close