The Survey of London’s favourite festive photographs

By the Survey of London, on 21 December 2017

Thank you for taking the time to read the Survey of London’s blog posts over the last year. Here follows a selection of our favourite festive photographs from our past and current studies of the capital’s built environment. Happy Christmas and all good wishes for the New Year.

Oxford Street

The character of Oxford Street is defined above all by its shops, and Christmas is its busiest time of the year. In 2015 we asked Lucy Millson-Watkins to photograph the lights, sights and decorations of Christmas on Oxford Street. Here is a selection of the photographs that she took, first published online in a blog post which considered the festive season on Oxford Street and its enduring traditions.

Oxford Street at dusk, looking east. (© Survey of London, Lucy Millson-Watkins)

Christmas bauble decorations strung across Oxford Street in December 2015. (© Survey of London, Lucy Millson-Watkins)

Boots, with understated decoration. (© Survey of London, Lucy Millson-Watkins)

Whitechapel

Last December it was announced that the Whitechapel Bell Foundry would close in May 2017, and this year has witnessed its closure and the end of what has been a remarkable story. Business cards claim the bell foundry as ‘Britain’s oldest manufacturing company’ and ‘the world’s most famous bell foundry’ – the first not readily contradicted, the second unverifiable but plausible. The business, principally the making of church bells, had operated continuously in Whitechapel since at least the 1570s. It had been on its present site with the existing house and office buildings since the mid 1740s. Derek Kendall’s wintry photographs of the bell foundry in 2010 provide an insight into its historic buildings and the preservation of traditional craftsmanship until its closure. If you would like to read the Survey’s full account, please click here to find the draft text on the Survey’s ‘Histories of Whitechapel’ website.

Shopfront at the east end of 32–34 Whitechapel Road in 2010. (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Inner yard of the bell foundry, looking north-west in 2010. (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

Tuning shop in 2010. (© Historic England Archive, photographed by Derek Kendall)

University College London

There is a Survey of London monograph on University College London in the offing. UCL’s first architectural expression was the grand neoclassical building constructed in 1827–9 to designs by William Wilkins, its portico and dome a prominent statement. Only the central range of this scheme was completed, yet successive wing extensions have formed a dignified quadrangle in Gower Street.

The Corinthian portico and dome of the Wilkins Building is instantly recognizable and has been adopted by UCL as its logo. (© UCL Creative Media Services, Mary Hinkley)

View of the Wilkins Building from Gower Street, looking east. (© UCL Creative Media Services, Mary Hinkley)

Even the railings in front of the Cruciform Building, formerly University College Hospital, received a generous helping of snow in February 2009. Alfred and Paul Waterhouse’s triumphant red-brick and terracotta hospital was built on a cruciform plan in 1896–1906. (© UCL Creative Media Services, photographed in 2009 by Mary Hinkley)

Battersea

Clapham Common is one of London’s most-prized public spaces, notable for its wide-open character and the clear sense of definition and urbanity imposed by its boundaries. An essentially triangular and uniform area of some 220 acres, it has lost less ground to development than most metropolitan commons. Archery was a popular pastime in the eighteenth century, as were boxing and hopping matches, and occasional fairs which attracted larger gatherings. Today the common boasts a mixture of formal and informal planting, tree-lined roads, sports facilities, play areas, and broad open spaces. The ponds and the bandstand (1890) are notable remnants of improvements effected in the nineteenth century, when cricket, football, tennis, golf, horse riding, model yachting and bathing were all enjoyed on the common. If you would like to read the Survey’s full account of Clapham Common from the Battersea volumes (published in 2013), please click here to download the draft chapter on ‘Parks and Open Spaces’ from our website.

Clapham Common, the north-western panhandle under snow in 2013. St Barnabas’s Church on Clapham Common North Side is within view in the distance, its pitched roofs adorned by a dusting of snow. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Sledging on Clapham Common in 2013. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Clapham Common under snow in 2013, view towards Clapham Common North Side. (© Historic Englnad, Chris Redgrave)

South-East Marylebone

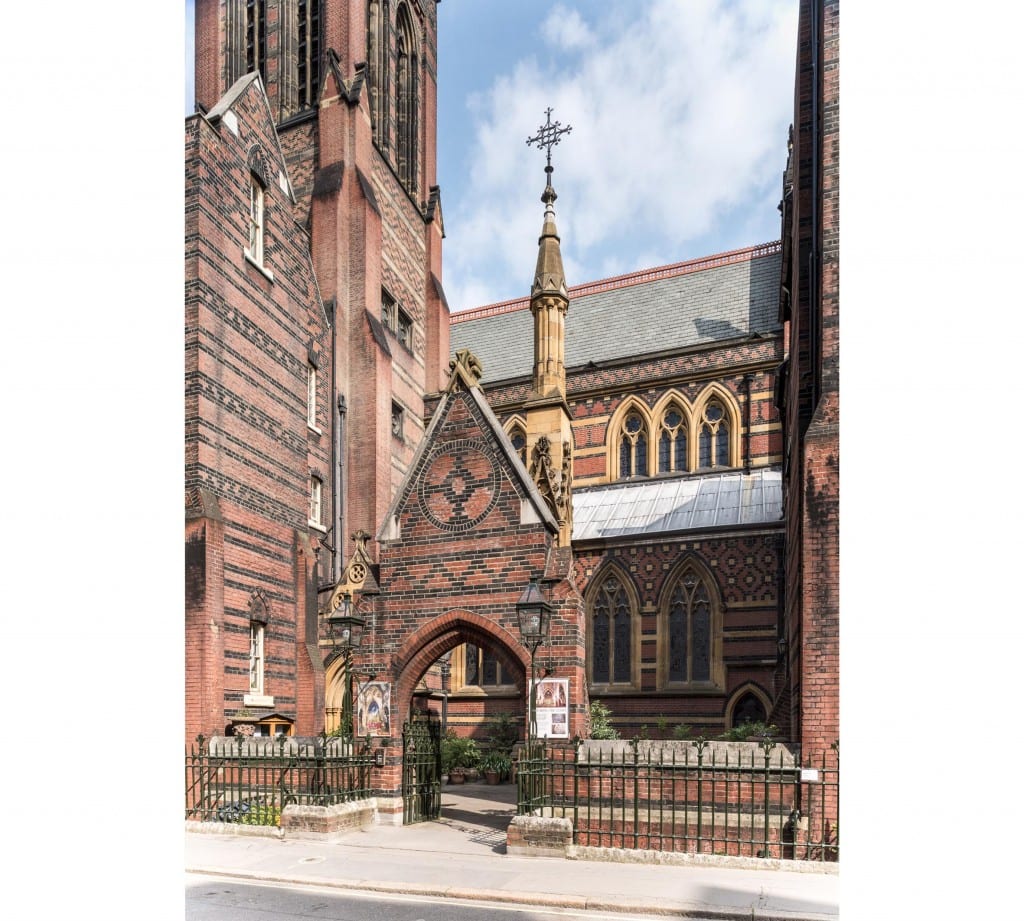

The brick church and lofty spire of All Saints, together with the twin clergy and parish buildings that front it towards Margaret Street, comprise a renowned monument to Victorian religion and architecture. Exuberant and compact, the group was built in 1850–2 by John Kelk to designs by William Butterfield, yet the interior of the church with its painted reredos by William Dyce was not completed and opened till 1859. Butterfield continued to embellish and alter All Saints throughout his lifetime, and it is always regarded as his masterpiece. Among decorative changes to the interior since his death, the foremost were those made by Ninian Comper between 1909 and 1916. Recent restorations have reinforced Butterfield’s original vision of strength, experimental colour and sublimity. A full account of this astonishing church has been published in the Survey’s volumes on South-East Marylebone, published in 2017. Please click here to read the account of All Saints’ Church in the Survey’s draft chapter on Margaret Street.

View of All Saints’ Church, Margaret Street from the west. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

North aisle, looking north-east. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Nativity scene on the wall of the north aisle. The tilework at All Saints was designed by Butterfield, painted by Alexander Gibbs and executed by Henry Poole & Sons in 1875–6. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Close

Close