South-East Marylebone Old and New

By the Survey of London, on 24 February 2017

In 2017 the Survey of London will publish two volumes (Nos 51 and 52) covering a large swathe of the parish of St Marylebone, an area comprising much of the West End north of Oxford Street, otherwise bounded by Marylebone High Street and the Marylebone Road, west and north, and Cleveland Street and Tottenham Court Road to the east. Like many of London’s place-names, Marylebone means different things to different people. To some it connotes the Marylebone Road and its penumbra, scarred by grinding traffic, to others the area adjacent to the two Marylebone Stations, main-line and underground, while those with a sense of civic history may call to mind a once-proud parish stretching from Oxford Street through St John’s Wood to the edge of Kilburn. By far the most famous association is with Lords, and the Marylebone Cricket Club founded in 1787. But the enduring image of Marylebone as a district is of the grid of alternating streets and mews, leavened by the occasional square, that picks up the West End’s uncertain structure beyond Oxford Street and shakes it into order and urbanity.

The aura of south-east Marylebone is various. Time-honoured medical connections have bequeathed cosmopolitanism and gravity to the central grid. Here patients for private clinics or guests at serviced apartments and hotels alight at the kerbside, chauffeurs linger on the qui vive for parking attendants, and pedestrians scurry rather than saunter, pressed forward by the rhythm of the streets. A mundane mews behind may be disrupted by a vision of nurses on tea-breaks clad in overall green, or a lorry backing in with oxygen canisters. Marylebone High Street and its boutiques draw their constituency of well-heeled shoppers and loafers. Yet Paddington Street Gardens and Marylebone Churchyard close by convey an air of ease, with old people reflective on benches or gaggles of schoolchildren on the grass. Lunchtime sprawlers in Cavendish Square are different – a mélange of shop assistants, office workers and tourists taking their breaks. On the fringes of Fitzrovia, the livelier portions of Great Titchfield Street and its surroundings exude conviviality, mixing pubs, small shops and cafés even now not all gentrified, patronized by the copious media businesses that have spread outwards from the BBC and taken over the premises of the dwindling garment trade.

Parts of south-east Marylebone have resisted change during the last century. The following photographs taken by Bedford Lemere & Co. at the turn of the nineteenth century are shown alongside recent photographs by Chris Redgrave.

Debenham and Freebody department store during construction, 27–37 Wigmore Street, in 1907 (Historic England Archive)

Former Debenham and Freebody department store, 27–37 Wigmore Street, in 2013 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The south side of Wigmore Street offers a sudden change in scale and monumentality with the silvery bulk of No. 33, built as headquarters for the drapery business of Debenham & Freebody in 1906–7. A public offer was made in 1907 to help pay for a grand reconstruction of the Wigmore Street premises, ‘rambling and incoherent’ after 90 years of piecemeal development. The London Scots architects William Wallace and James Glen Sivewright Gibson were chosen to design the new building. The frontage was conceived as symmetrical across the whole of the block, but because of the bank there is an extra bay at the west end, devoted originally to a discrete fur shop. A giant arcade runs across the ground and first floor, with plate-glass windows to what were originally single large shops either side of the entrance, their semi-circular tops lighting the first-floor showrooms. Three segmental pediments top three bays set slightly forward with paired giant-order Corinthian columns of grey-green Truro marble forming a vestigial screen to the third and fourth floors. Decoration is mostly channelled ‘stone’ work to the first floor, applied garlands, and two seated female figures within the central pediment, all executed in Doulton’s Carrara Ware. Crowning all is a columned lantern-turret on an octagonal plinth.

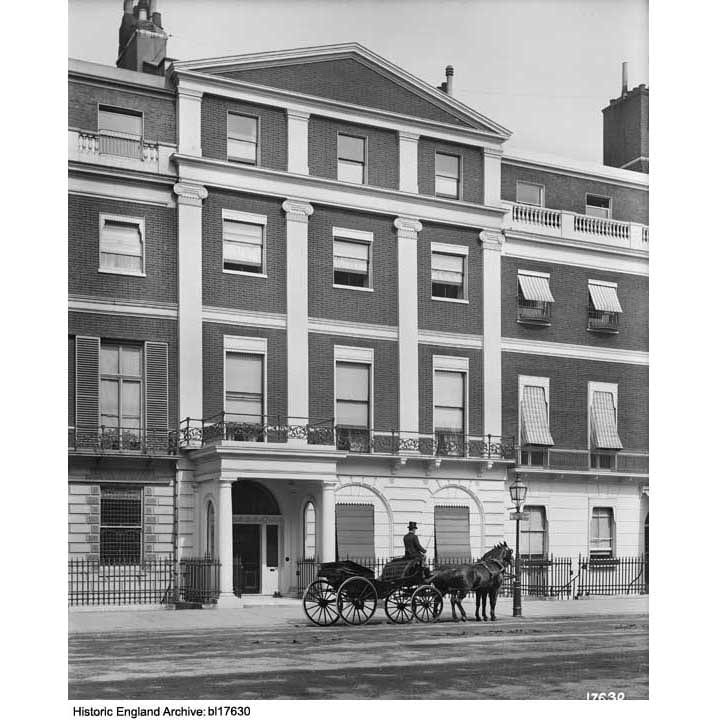

46 and 48 Portland Place in 1903 (Historic England Archive)

46 and 48 Portland Place in 2013 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Nos 34–60 is the best run of surviving Adam-period houses in Portland Place, still with its eye-catching stuccoed and pedimented central pair at Nos 46 and 48, with their ingenious mirrored angled entrance doors. It is here that one gets the strongest sense of the Adam brothers’ original palace-front design concept. Various alterations have changed the appearance of the middle pair at Nos 46 and 48, marring though not completely obliterating the powerful original composition. Its crowning balustrade has gone but for once, when the upper floor was extended around 1870, rather than building up the front wall as elsewhere in the street, the builders left the central pediment in situ, with an enlarged mansard roof and dormers rising behind. Like its partner opposite (No. 37, now demolished), this façade was faced entirely in stucco and decorated with a frieze, pilasters, roundels and characteristic Adam panels of griffins and urns of the same material. Unusually the rusticated ground floor has the windows flanking the entrance set within relieving arches. Particularly elegant is the shared entrance within a shallow apse under a segmental arch, with the two doorways set at an angle.

28 Portland Place in 1903 (Historic England Archive)

28 Portland Place in 2015 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

No. 28 Portland Place retains its Adam pediment and Ionic pilasters (though both were raised in the nineteenth century to accommodate an extra storey), as well as a later Doric entrance porch. Despite many changes it still exudes an aura of old-world elegance. Though it was sold by the Goslings to the Institute of Hygiene in 1928 and has been in institutional or corporate use ever since, No. 28 is still a first-rate example of a London society townhouse adapted and added to over time by one family. The interiors have survived well, of which the most notable is an exceptionally fine ballroom, comprising a suite of linked first-floor drawing rooms fitted out in an elaborate late-Victorian Adam Revival style, with an abundance of painted and gilded plaster decorations and a figurative front-room chimneypiece in the manner of Wyatt.

11 Harley Street in 1903 (Historic England Archive)

11 Harley Street in 2013 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

9 and 11 Harley Street are tall red-brick rebuildings, of 1891 and 1886 respectively, in similar styles, with plentiful stone dressings and pediments. No. 9 was designed by F. M. Elgood as a speculation for W. H. Warner (of Lofts and Warner, estate agents). Elgood was also involved in the design of No. 11, one of his earliest works in the area, whilst still in partnership with Alexander Payne (to whom he was articled) as Payne & Elgood. Their client was the physician and surgeon William Morrant Baker. The building was extended to the rear in 1906 for another doctor, the dermatologist J. M. H. McLeod. Stone figures on the gable were removed in 1937.

Bedford & Co. offices at 24 Wigmore Street in 1894, No. 22 to the right (Historic England Archive)

18–24 Wigmore Street in 2014 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Nos 18–22 Wigmore Street were built by Holloway Brothers in 1892–3 to the designs of Leonard Hunt, as showrooms and offices for the piano manufacturer John Brinsmead & Sons. The business, founded in 1837, moved to No. 18 (then 4) in 1863 and subsequently expanded into 20 and 22. The works moved from Charlotte Street to Kentish Town in 1870, and by 1893 produced around 3,000 pianos a year. Hunt’s building, expensively finished with mahogany panelling and leaded glass, was ‘one of the sights of fashionable London’. The ground floor was given over to display space, divided by a hallway with pavement lights illuminating basement showrooms, the upper floor comprising offices and chambers. In 1895 a recital room was added at the back of the basement, seating 130. Lit from two sides with leaded windows, it had mirrored columns and fully-tiled walls. Bedford & Company, surveyors, had offices next door at No. 24. Brinsmeads went out of business in 1922, but was re-established at 17 Cavendish Square in 1924. Lloyds Bank acquired the Wigmore Street building, creating a strong room within the former recital room, and subletting the western shop, which retains a 1928 neo-Georgian bronze shopfront fitted for the opticians Curry & Paxton. The upper floors were converted to flats in 1933.

34 Weymouth Street in 1910 (Historic England Archive)

34 Weymouth Street in 2014 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

On the other side of Upper Wimpole Street, of 1908 in a strong, shaped-gable style, is 34 Weymouth Street, by F. M. Elgood for the developer W. H. Warner. Here the gables have oculus windows with attractively sculpted stone surrounds and festoons beneath, the work of A. J. Thorpe, who was also responsible for the carved stone consoles to the door surround.

30–31 Wimpole Street in 1917 (Historic England Archive)

30–31 Wimpole Street (left) and 30a and 30b New Cavendish Street (right) in 2014 (Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Though treated as one architectural piece, this large and imposing Portland stone corner block of 1910–12, extending round the corner into New Cavendish Street, appears to have been a joint redevelopment and was built as four separate ‘houses’, each originally comprising doctors’ consulting rooms on the lower floors and residential accommodation above. The two properties facing Wimpole Street (originally numbered 30 & 31) were designed by F. M. Elgood, working for the developer Samuel Lithgow. But the two houses fronting New Cavendish Street (30a & 30b) were by Banister Fletcher & Sons, acting for Dr James Lennox Irwin Moore, who had consulting rooms at 30a – and it was these two ‘doctors’ houses’ that attracted attention in the architectural press. The style is a muscular free Jacobethan, with mullioned and transomed windows, and a stone balcony resting on decoratively carved console brackets, all topped off by pedimented gables with deep modillion eaves – offering a strong contrast to Wimpole House opposite, with its dressing of florid salmon-pink terracotta. The composition is stylistically dissimilar to most of the Edwardian buildings on the Howard de Walden estate (and is none the worse for that) but there are a few oddities about the design. For instance, above the deep modillion cornice on the New Cavendish Street elevation, instead of gables as elsewhere, broad dormers flank a flat-roofed pavilion with a concave façade in what appears to be Bath stone but is probably coloured render. In terms of their construction, the buildings made use of expanded-steel reinforced concrete, with interiors awash with oak panelling and polished oak to the floors and staircases.

In advance of the publication of Volumes 51 and 52 of the Survey of London, on South-East Marylebone, in 2017, the draft chapters have been made freely available online.

Close

Close