Montagu House, Portman Square: the story of a lost Georgian town palace

By Survey of London, on 17 September 2021

This blog post was written for the Survey of London by Rory Lamb, a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh, who researched the history of Montagu House for the Survey this summer, during a two-month work placement funded by the Scottish Graduate School for Arts & Humanities Doctoral Internship Programme. Rory’s research will contribute towards the Survey’s study of South-West Marylebone, scheduled for publication as volume 56 in the Survey’s ongoing series of area volumes. (Volumes 54 & 55, on Whitechapel, are the next volumes to be published, in June 2022.)

Until the mid-1950s, the site of the Nobu Hotel and Portman Towers at the north-west corner of Portman Square in Marylebone was occupied by Montagu House, a freestanding townhouse set in one of London’s largest private gardens. Latterly the town residence of the Portman Estate’s landlords, the Viscounts Portman, it was for a century occupied by the descendants of Mrs Elizabeth Montagu, the celebrated eighteenth-century writer and hostess for whom it was executed between 1775 and 1791. In Private Palaces of London (1908), Edwin Beresford Chancellor summed up her significance for the building:

Perhaps hardly another important mansion in London is so closely identified with a single individual as is the great house in Portman Square with its first owner. This is due to two reasons, one of which is the close and almost tender interest taken by Mrs Montagu in its construction and decoration; and the other the renown of the lady herself.

Mrs Montagu was the author of a famous essay on Shakespeare and a leading member of the Bluestockings, a group of men and women who met to discuss literature and philosophy at her London houses and those of her friends. Gambling and politics were banned from Mrs Montagu’s gatherings, which usually took the form of a sumptuous breakfast, tea or dinner followed by group conversations on intellectual subjects. From the 1750s her salon at No 23 Hill Street in Mayfair was attended by the likes of Edmund Burke and Sir Joshua Reynolds and sought out by literary visitors to London from abroad. When her husband, Edward, died in 1775, Mrs Montagu inherited a large fortune and set about constructing a new house in Marylebone which would offer an expanded capacity and a more magnificent setting for her hosting. For her architect she turned to James ‘Athenian’ Stuart (not Robert Adam as has sometimes been claimed), whom Mrs Montagu had previously employed at Hill Street and whom she had assisted in publishing the Antiquities of Athens in the 1760s.

Elizabeth Montagu (née Robinson) by John Raphael Smith after Joshua Reynolds, 1776 (© National Portrait Gallery, London [reference: NPG D13746], shared without changes under a CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 license).

Montagu House, illustrated by T. H. Shepherd, 1851 (from Mrs Montagu, ‘Queen of the Blues’: Her Letters and Friendships from 1762 to 1800, Vol. 2, edited by Reginald Blunt [Boston and New York, 1923], p.110).

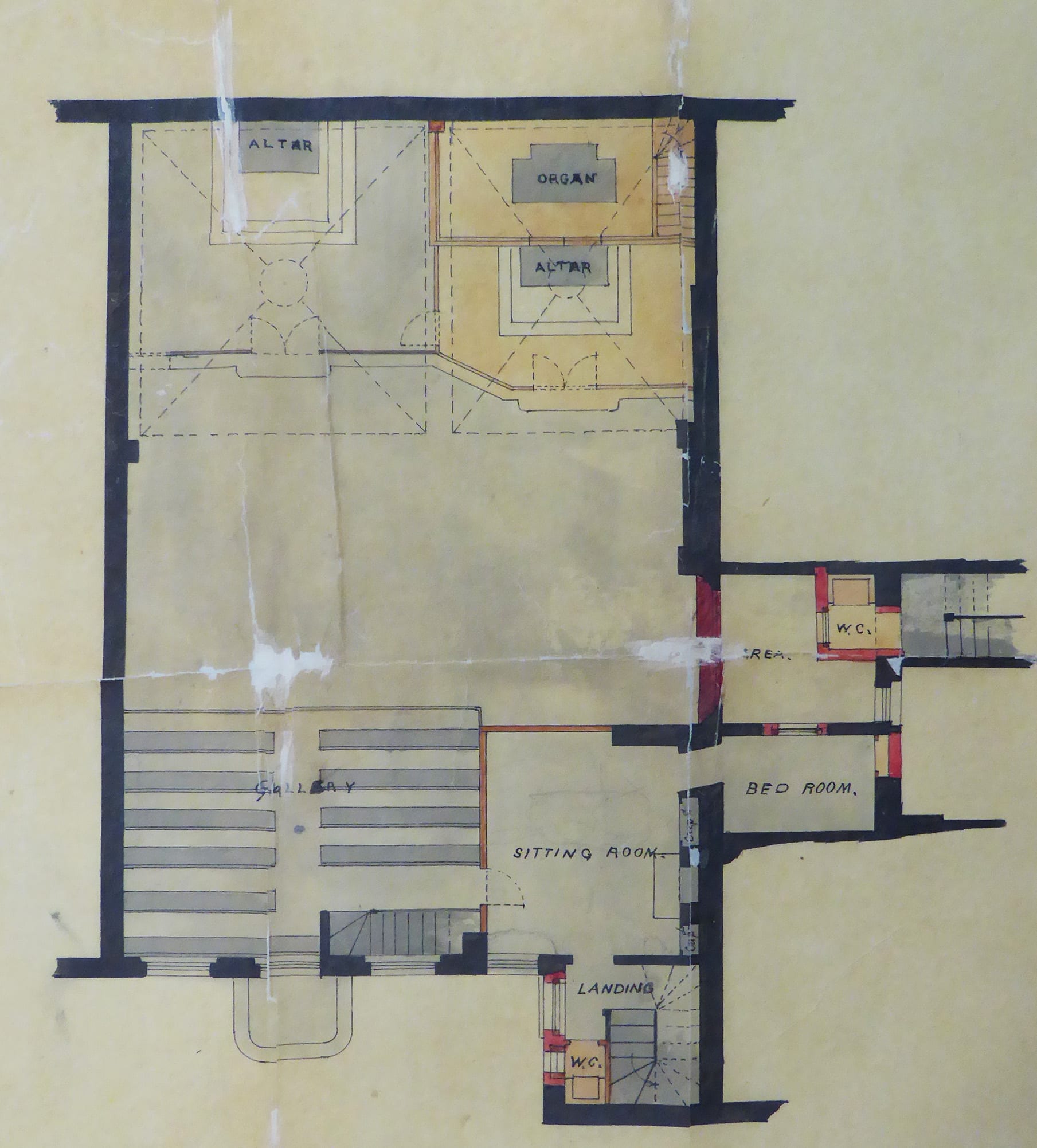

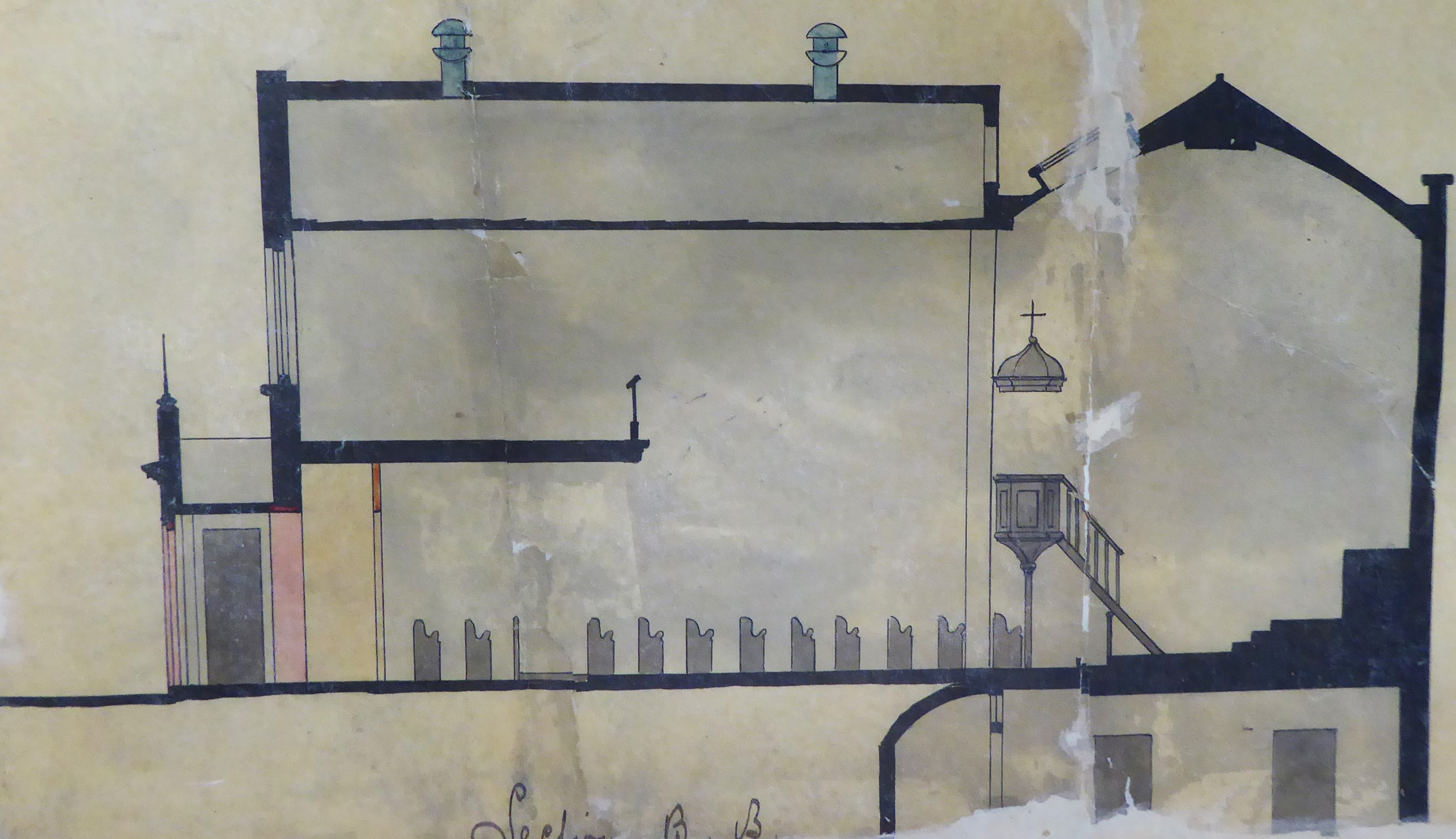

The interiors of the principal apartment were decorated over the next four years before Mrs Montagu was able to take up residence in December 1781. These comprised a ground-floor staircase hall rising to a circuit of four reception rooms: an antechamber, dining room, morning room (giving access into Montagu’s private apartment) and gallery. The antechamber was decorated in the Pompeiian style by Biagio Rebecca and Giovanni Battista Cipriani akin to the painted room of Spencer House, and the gallery featured paintings on Shakespearean subjects as the backdrop for Montagu’s literary gatherings. The ceilings offered delicate geometric and floral patterning in the hall and dining room, with more elaborate coffered coving in the morning room and an elliptical vault of interlocking fans and scrollwork with paintings by Angelica Kauffman in the gallery. ‘All the celebrated artists in England of the present times have done something towards embellishing my house’, wrote Mrs Montagu to Lord Kames in December 1781, ‘but its best grace is simplicity’. A small suite of three rooms had also been fitted up on the ground floor beneath Mrs Montagu’s bedroom for her friend Leonard Smelt, tutor to two of George III’s sons, and his wife during their visits to London. From 1780 Smelt had co-ordinated ticketed public visits to the new reception rooms in the final stages of their completion. Despite the craftsmen’s concerns that visitors would damage the paint and gilding, Mrs Montagu insisted tickets should be widely distributed so as to show off her new house to the whole of London society.

The dining room, 1904 (from A Later Pepys: the correspondence of Sir William Weller Pepys etc., Vol. 2, edited by Alice C. C. Gaussen [London, 1904], p.279).

The morning room in 1894 (Historic England Archive, Bedford Lemere Collection, BL12699).

However, Stuart himself, and his unsatisfactory assistant, James Gandon, seem to have been dismissed some time in 1780-1, Stuart’s drunkenness and incompetence with the workmen sitting at odds with Mrs Montagu views of decorous behaviour and the close eye she kept on budget and efficiency in her affairs. He was replaced as architect by Joseph Bonomi, assisted by her head carpenter, Charles Evans. When Mrs Montagu moved in most of the ground-floor rooms and the great room of the first floor remained incomplete and work on these resumed between 1789 and 1791. During this period the first-floor morning room was transformed into her feather-room, celebrated in verse by William Cowper, with timber panels hung with tapestries of exotic feathers collected by Mrs Montagu’s friends over the preceding decade. The focus of the new work, however, was the decoration of the great room to a handsome Neoclassical design by Bonomi. This was a much richer interior than Stuart’s earlier rooms, dominated by fourteen scagliola Corinthian pilasters, with profuse gilding, marble chimneypiece and window architraves, and a segmental ceiling of elaborate plasterwork. Montagu intended the luxurious decoration as a ploy to rival worldlier London hosts with a set piece of similar magnificence that would attract younger members of society to her polite parties and away from more debauched venues elsewhere. Bonomi’s grand interior was opened in great state by members of the royal family and celebrated in the St James’s Chronicle. Although the intellectual heyday of the Bluestockings was seen to have been at Hill Street, Mrs Montagu’s entertainments continued at Portman Square to increased scale and grandeur until her death in 1800, with breakfasts and teas attended by several hundred people.

The great room in 1894 (Historic England Archive, Bedford Lemere Collection, BL12693).

The semi-rural location of the house originally attracted Mrs Montagu, with an urban front to Portman Square but a rear elevation giving views from the first-floor dining room over fields to the Hampstead Hills. By the time of her death in 1800 much of this open character still remained but as Marylebone spread north and obscured the view a considerable green space was preserved by the Montagu House garden, expanded in 1789 but originally laid out by Mrs Montagu’s friend George Harcourt, 2nd Earl of Harcourt, whose flower gardens at Nuneham Courtenay in Oxfordshire she had admired. These also had an intellectual bent, Harcourt’s garden designs being inspired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s ideas of philosophical contemplation in nature. However, the gardens of Montagu House were best remembered for playing host to Mrs Montagu’s annual chimneysweeps’ dinner, held on May Day from 1789 in the forecourt to the square. The meal was open to all of London’s sweeps who were served roast beef and plum pudding by her footmen on trestle tables and became something of an annual society spectacle.

Montagu House and gardens with the new stable block in 1895 (Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland).

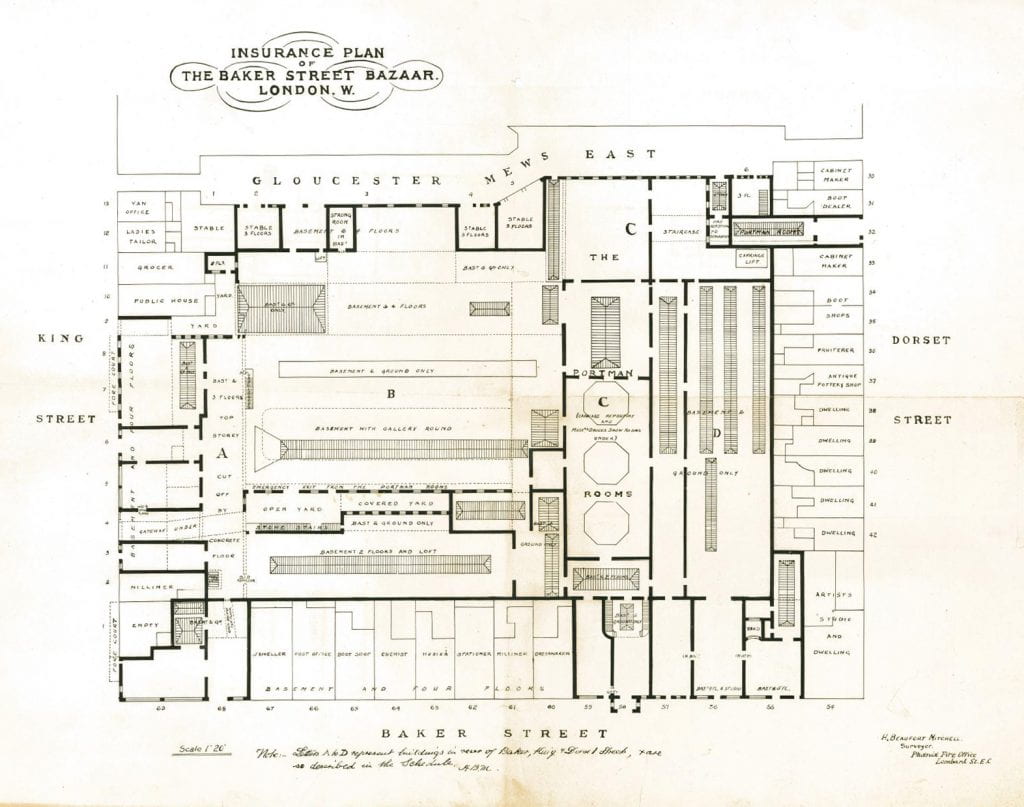

Montagu House remained in Elizabeth Montagu’s family until 1872, when Selby’s original 99-year leases reverted to the Portman family. It was then occupied by Mrs Montagu’s adopted heir and nephew, Matthew Robinson Montagu (latterly 4th Baron Rokeby), and his children, concluding with his younger son General Henry Montagu, 6th Baron Rokeby. In 1872 the general, a veteran of Waterloo now resigned to a wheel-chair due to gout and old age, was forced to vacate the family home for a house in Stratford Place. He was replaced by William Henry Berkeley Portman, MP, who had been living on the south side of Portman Square for several years. Before succeeding as 2nd Viscount Portman in 1888, Portman had already made considerable changes to Montagu House, possibly under the direction of the incumbent RIBA president, Thomas Henry Wyatt, who was commissioned for survey drawings in 1872. The Ionic doorway was extended into a large porte cochere of Portland Stone and matching bracketed balconies added to the first floor Serlian windows. An attic story with additional bedrooms and pedimented dormer windows was added to the garden front, and an early lift system was inserted into the void of the service stair. Portman also cut back the now mature gardens and gave over a large area of ground on the north side for a new courtyard stable block opening on to George Street.

Exterior view of 22 Portman Square, photographed in 1894 (Historic England Archive, Bedford Lemere Collection, BL12691).

The Portman family continued in occupation of the house until the Second World War, when it was gutted by an incendiary bomb during an air raid in 1941. It stood as an empty shell for about a decade before being demolished in the early 1950s along with the undamaged stable block. One of the last surviving features of Montagu House was a set of Stuart’s gate piers, which were relocated to Kenwood House in Hampstead. The site was briefly used for a car park before the construction of the present hotel and flats. Although the grand mansion has been lost, Mrs Montagu’s name is preserved in Montagu Street, west of the block on which the house stood, while her earlier house at Hill Street (now No. 31) was rediscovered in 2003 with intact interiors by Stuart and Robert Adam. Since then, the Bluestockings have been a popular subject for scholarship, Mrs Montagu remaining a central figure, with the result that her significance as an architectural patron is now better recognised alongside her intellectual achievements.

Close

Close