Discovering Dombrovsky

By Sarah J Young, on 17 January 2014

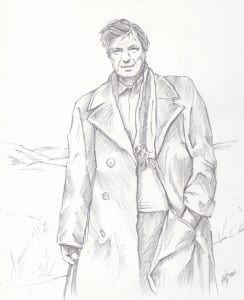

Yuri Dombrovsky by Gregory Lindsay-Smith.

© Gregory Lindsay-Smith.

Reproduced with permission of the artist.

Jekaterina Shulga reflects on the work of an extraordinary Soviet writer, Yuri Dombrovsky, and the limitations of formal literary analysis for dealing with such an unusual figure.

I remember the first time I read Yuri Dombrovsky’s novel The Keeper of Antiquities well. I was exploring writers to research for my thesis on trauma and narrative. Trauma seemed to be absent from this novel, but it had something else and I couldn’t put my finger on exactly what. And this is how Dombrovsky writes, always with a surplus, making us feel that there is forever more to it than meets the eye. That convinced me that he is one of the greatest Russian writers of the 20th century, but he has never achieved the attention or recognition he deserves. Although most Russian literature scholars will nod their heads and smile when you mention Dombrovsky, usually followed by “I really like The Keeper” or “he’s really interesting”, very few have researched or written about him. Most of what we know about Dombrovsky comes from a small number of sources and often it is based on anecdotal evidence. People want to talk about what he was like, not where he lived or what he did.

This is because Dombrovsky really was a fascinating character. He lived during the most repressive time in 20th-century Russia, and yet he remained rebellious, defiant and a lover of freedom. Born in 1909 in Moscow, he became interested in literature as a young boy, a passion would sustain him throughout his life, giving him the strength to fight for what he believed was right, even though it came at a great cost to himself. However, his righteousness was also infused with a large portion of rebelliousness and defiance. He often referred to himself as a gypsy and a hooligan. This is no Solzhenitsyn-like prophet.

In 1932, soon after starting his studies in literature he was arrested and exiled to Alma-Ata (now Almaty), where he lived until 1956. During his exile he worked at the remarkable Zenkov Cathedral, which had been turned into a museum, and taught literature and drama at various institutions. He was arrested a further three times, spent several years in the hard labour camps of Kolyma and elsewhere, and was released as an invalid. It took Dombrovsky many years to recover from these experiences, but he rarely writes about the Gulag. It is only in his poetry that we catch a glimpse of this dark period in his life. But even here there is a contrast between the terrifying subject of the camps and a light and cheerful rhythm and rhyme. Similarly, his fiction represents the darkest period of Stalin’s oppression in a surprisingly colourful and engaging manner.

His two major novels, The Keeper of Antiquities and The Faculty of Useless Knowledge, are both set in Alma-Ata and depict the life of a museum keeper working for the central Kazakhstan Museum in the Zenkov Cathedral. The novels are largely based on Dombrovsky’s life, yet they are fictional and blend his own experiences with his artistic expression. Dombrovsky suggested that some things are difficult to speak about oneself, so it seems that fiction allowed him to delve into his experiences in a deeper way. (more…)

Close

Close