Folk Psychology: more than nationalist pseudo-science?

By Sean L Hanley, on 23 September 2013

Egbert Klautke talks about his new book, which re-evaluates the historical discipline of ‘Folk Pyschology’ in Germany. It was, he argues, more than nationalist pseudo-science.

Egbert Klautke talks about his new book, which re-evaluates the historical discipline of ‘Folk Pyschology’ in Germany. It was, he argues, more than nationalist pseudo-science.

BB: How would you define ‘Folk Psychology’ and what drew you to the study of it?

Egbert Klautke: ‘Folk Psychology’ is an awkward translation of the German term Völkerpsychologie. Originally, it referred to attempts to study the psychological make-up of nations, and as such is a forerunner of today’s social psychology. However, in today’s common understanding, Völkerpsychologie equals national prejudice: it is seen as a pseudo-science not worth considering seriously.

My first book dealt with perceptions of the U.S.A. in Germany and France, and much of these views could be described as Völkerpsychologie: clichés and stereotypes about a foreign nation, which were of a surprisingly coherent nature. Back then, my rather naïve idea was that there must be a general theory behind these perceptions, and I embarked on a study of Völkerpsychologie.

BB: Did any perceptions on the subject change from the time you started your research to the time you completed the book?

EK: When I started my research, I shared the general view of Völkerpsychologie as a flawed attempt to present national stereotypes as academic research, and was suspicious of its nationalist agenda and racist undertones. I also considered it typically German. Having completed the book, I have a much more sympathetic view of ‘folk psychology,’ at least of the early attempts by [Moritz] Lazarus, [Heymann] Steinthal and [Wilhelm] Wundt. Despite its flaws and shortcomings, Völkerpsychologie was a serious and honourable attempt to introduce a social science to the university curriculum. As such, it influenced pioneers of the social sciences not only in Germany, but also around the world.

BB: What are some of the factors that led to the demise of this kind of psychology?

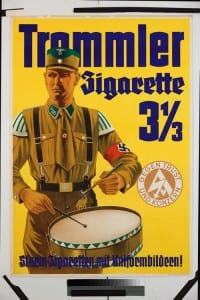

EK: Most importantly: the Third Reich. Even though the Nazis were not particularly interested in ‘folk psychology’ after 1945 this approach was quickly associated with Nazi theories and race ideologies. The genuine weaknesses of ‘folk psychology’ contributed to its demise, but it was mainly the assumption that Völkerpsychologie was part of Nazi thinking that contributed to this process. By the 1960s, the very term had become a taboo in the social sciences. (more…)

Close

Close