Will Brexit affect growth prospects in the EU Members of Central and Eastern Europe?

By yjmsgi3, on 26 May 2016

Chiara Amini – Teaching Fellow in Economics and Business and Raphael Espinoza – Lecturer in Economics

UCL SSEES Centre for Comparative Studies of Emerging Economies

It is a common view that a UK exit from the European Union would cause significant damage to the UK and to the EU. The Treasury claims that Brexit would make Britain significantly poorer and could result in GDP contracting by as much as 6%. Such a significant impact would not be so surprising, given that trade and investment between the UK and Europe has grown significantly in the last 40 years. In 2014 a study by Ottaviano et al showed that Brexit trade losses would amount to 3.6% of UK GDP, as a result of an increase in taxes, quotas and regulatory legislation. What’s really striking is the fact that these losses have the potential of reaching 10% of GDP, if we consider the dynamic effect of trade on innovation and competition. Earlier this year, JPMorgan estimated that Brexit could reduce GDP growth by as much as 1% between 2016-17. At the same time the bank also warned that Brexit could decrease Eurozone GDP by 0.2-0.3%.

Policymakers in the EU countries of Central and Eastern Europe have been vocal in expressing their concerns about Brexit. The countries this specifically refers to are: The Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. Recently Poland’s President, Andrzej Duda, warned that Brexit could have dramatic consequences for the Polish economy. However, formal analyses estimating the impact of Brexit on the region number on the fingers of one hand. Erste Bank argues that direct economic consequences on the region would be relatively minor as UK trade amounts to only 3-6% of total trade. However, countries such as Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and Slovakia, that run trade surpluses with the UK, are predicted to be most affected. After looking at the macro data, we can argue that Central and Eastern Europe would not only be affected by Brexit directly via a fall in flows from the UK, in terms of migration and remittances, trade and financial flow, but also indirectly through its effect on the Eurozone. As economic shocks spread easily from one country to another, a phenomenon known as ‘financial contagion,’ the impact of Brexit on the Eurozone would further reduce inflows to Central and Eastern Europe.

Financial flows from the UK to Central and Eastern Europe appear moderate (see Figure 1). The median of UK financial flows to GDP is less than 1%. Trade flows (import and export) are much more important, and they represent around 2.5% of GDP in Central and Eastern Europe.

Figure 1– Median Flows UK- Central and Eastern Europe

However, taken together, UK trade and financial flows make up a sizeable share of the total flows to the region. The proportion of UK remittances to total remittances in Central and Eastern Europe is as high as 8%. As far as trade is concerned, this ratio is 4%. Inevitably, some countries in the region have even stronger links with the UK; for instance, in the Czech Republic, foreign direct investment from the UK constitutes 14% of its total foreign direct investment. Also in the Czech Republic, bank loans from the UK represent 2.5% of GDP. UK remittances also constitute an important part of total remittances sent to Latvia and Lithuania, over 20% of the total.

Moreover there has been a high degree of correlation in the economic growth between Central and Eastern Europe and the UK. This could be the result of financial contagion via other, third party countries. Alternatively, it could stem from both regions’ high integration with the two largest world economies, the US and the Eurozone. However, the correlation between growth in Central and Eastern Europe and the UK (at 0.56) is higher than that between the US and Central and Eastern Europe. (0.43, see Figure 2) Disentangling such correlations so as to understand how economic shocks are transmitted between countries has been done in a variety of models.

Figure 2 – Real GDP growth (Year-on-Year; source: OECD and IMF)

Our analysis shows that the UK is a significant source of financial contagion for Central and Eastern Europe. If, as a pessimistic example, estimated by PwC earlier this year, UK GDP fell by 5% as a consequence of Brexit, this would reduce GDP growth in Central and Eastern Europe by no less than 2.5%, as a consequence of third party financial contagion. Since the model is linear, if the fall in UK GDP was only 1%, the impact on Central and Eastern Europe would be only 0.5%.

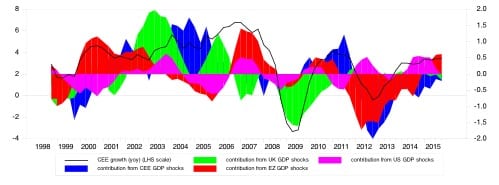

Historically, shocks to UK GDP have contributed around 20 % of the variance in growth in Central and Eastern Europe. In our research for this piece, we employed a well-known statistical methodology, Vector Auto Regression, to examine how growth in Central and Eastern Europe relates to the economic performance of the UK, US and Europe. The historical decomposition of growth in Central and Eastern Europe (Figure 3) attributes the good performance of Central and Eastern Europe in the first decade of this century to strong growth in the UK. This occurred at a time when growth in the Eurozone was disappointing.

Figure 3. Historical decomposition on GDP growth in Central and Eastern Europe (YoY)

We have come to the conclusion that, although it is uncertain what the short-term impact of Brexit on the UK will be, there are good reasons to think that it will have negative repercussions on Central and Eastern Europe.

Please note: Views expressed are those of the author(s) and not those of SSEES, UCL or SSEES Research Blog.

Close

Close