Crystal Palace (F. C.): Chernyshevsky’s barmy army

By Sarah J Young, on 30 May 2013

Sarah J. Young finds a rich history of Russian connections to the Crystal Palace, the glass and iron building by Joseph Paxton for London’s 1851 Great Exhibition.

When one thinks of Russian connections to English football, it is most likely the owners and shareholders of certain premier league clubs that will to spring to mind, or the small number of Russians who have played for English clubs, including Roman Pavlyuchenko and Andrei Arshavin. But as Crystal Palace F. C. reaches the premiership following a tense play-off final against Watford, the status of the club as possibly the only one in the English league to be named after a building – its former nickname the Glaziers emphasizing the connection to the iconic structure, which still features on the club badge – provides a legacy of historical and literary Russian resonances that far outstrip the transient presence of mere players and owners, or indeed football itself.

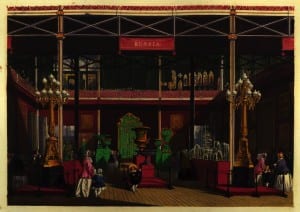

The Great Exhibition was intended, among other things, to bring together the industry of all nations for the promotion of peace and free trade (whilst, inevitably, demonstrating the superiority of Britain in all regards). The Russian exhibit drew attention owing to its late arrival, and was notable for the malachite products that stood out in a display mainly consisting of raw materials.

But in a climate of general xenophobia and fear of foreign revolutionaries who might visit the Exhibition – which took place three years after the 1848 wave of European revolutions – as well as intensifying Russophobia (the Crimean War was only two years away), it is perhaps not surprising that Russians themselves, as much as their manufactures, were seen to be on display. Among the exotic foreigners caricatured in descriptions and cartoons, the fearsome ‘Don Cossack’ always had his place alongside the Chinese mandarin and the African ‘savage’, reminding us how alien and un-European Russians seemed to the British imagination at that time. The notion of the palace as an international space may also have been behind the visit of Tsar Alexander II in 1874. As a later cigarette card commemorating the event indicates, the emphasis on this occasion was reconciliation and sameness – the Russians in the royal entourage pictured here are indistinguishable from the British guests – but the commentary on the reverse reminds us of that ‘other’, alien Russia, ending ominously: ‘The Tsar was assassinated by Nihilists on 13th March 1881.’

But if British views of Russians at the Great Exhibition simply reflected contemporary events and attitudes, within Russian literature the Crystal Palace assumed a particular significance, as it became a touchstone for debates about modernity, westernization and social transformation. (more…)

Close

Close