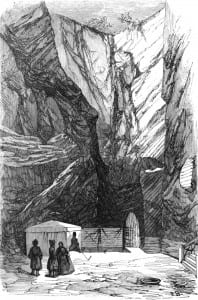

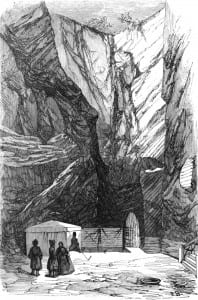

Le Proval a Piatigorsk.

Via Wikimedia Commons

In the final post before the SSEES Research Blog takes a short summer break, post-graduate student Benny Morgan reflects on the brief flowering of health tourism in southern Russia, and as a setting for Russian Romantic literature.

What the American temperance campaigner Diocletian Lewis (1823-1886) called the ‘mineral water mania’ of the mid-nineteenth century took a scientistic turn in the Russian Empire at around the same time as it did in Western Europe and the United States. In the 1860s the universities of Moscow and St. Petersburg examined a rash of medical dissertations on such topics as ‘The Effect on Blood Pressure of Baths and Showers at Different Temperatures’, describing in awed detail the results of douching experiments on rabbits and large dogs – and the language of the burgeoning hydropathic establishment trickled quickly into the promotional material of Russia’s self-proclaimed ‘watering places’.

By the century’s close, every southern town of note – Slaviansk, Borzhom, Piatigorsk – was producing brochures puffing the benefits of its waters, listing ailments treated and tabulating the testimonies of bathers and drinkers cured or ‘partially relieved’ of unpleasant symptoms. Yet spa therapy’s medicalization at mid-century also had the curious effect of sending the Russian watering place as a destination of fashion into apparently terminal decline. The empire’s Crimean and Caucasian resorts could compete neither infrastructurally nor rhetorically with the appeal of Baden-Baden, Wiesbaden and Vichy; dire comparative statistics – forty thousand visitors to Russian spas annually compared with half a million to German ones – drew hand-wringing about national ‘underdevelopment and lack of culture’ on the part of civic pamphleteers.

One marker of the commercial struggles of the Russian water-cure industry in the latter nineteenth century is the near-death of the southern spa theme in literature. Lidiya Veselitskaya’s Mimochka at the Waters (1891), a rare fin du siècle novel with a Russian health resort setting, makes fun of the westward trend in bathing culture by having its heroine ask, when a cure atKislovodsk is broached, ‘Aren’t there waters enough abroad?’ Foreign spas had monopolized the narrative as well as the therapeutic imagination.Despite their vivid ideological differences, both Dostoevsky and Turgenev look to Germany in their watering-place novels; the conspiratorial picture of resort culture given in The Gambler and Smoke (both 1867) offers perhaps the closest thing to a fictional consensus the two ever mustered. Tolstoy too, for all his creative investment in the Caucasus, takes the protagonists of his mature fiction to German spas in pastoral landscapes (see Family Happiness (1858) and Anna Karenina (1873-77)), not notionally domestic ones wedged into ravines.

Indeed, Chekhov’s minor-key masterpiece The Lady with the Little Dog (1899) draws for much of its melancholic atmosphere upon a sense that Yalta, another liquid mainstay of the Russian South, has become a place perpetually out of season: that the brightest heads have turned elsewhere. But for the critic with an interest in place and its ideological significance in fictions, a look back at the brief flowering of the southern cure has much to recommend it. The Romantic spa also offers itself as a point of departure for attempts to think through the attitudes that modern Russian literature has shaped and reflected with respect to cultures of health – and when tracing the ties that bind the realist spa text (Smoke), the bania tale in revolutionary skaz (Zoshchenko’s ‘The Bathhouse’ (1925)) and Brezhnev-era medical allegory (Solzhenitsyn’s Cancer Ward (1967)).

The Caucasian spa resort is a vital setting in Russian literature of the first decades of the nineteenth century. As Robert Reid has written, spa resorts in this period frequently serve as a microcosm of metropolitan social life. (more…)

Filed under Uncategorized

Tags: Aleksandr Bestuzhev-Marlinsky, Aleksandr Druzhinin, Aleksandr Shakhovsky, Caucasus, Chekhov, Dostoevsky, Lermontov, literature, Pushkin, Russia, Solzhenitsyn, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Zoshchenko

1 Comment »

Close

Close