Why Romania’s protests have failed to bring about real change

By Lisa Walters, on 20 September 2018

Dr Daniel Brett, Teaching Fellow in Social and Political Science, UCL SSEES

(This blog was originally posted on LSE’s Europe Blog on 19 September 2018.)

Romania has experienced large anti-government protests on multiple occasions in the last few years, most recently in August this year. Yet as Daniel Brett explains, the achievements of these protests have been modest and short-lived, with the country’s ruling Social Democratic Party still maintaining power. He highlights that while the protesters and opposition parties may be united in their opposition to corruption, they have radically different views on social and economic issues, hampering their ability to change the direction of Romanian politics.

Liberals against nationalism in Eastern Europe? It would have been a nice idea

By Sean L Hanley, on 25 July 2018

Photo: Tourbillon [CC BY-SA 3.0 ]

Some commentators say East Central Europe’s liberals made the fatal mistake of cutting themselves off from traditional nationalism. Seán Hanley and James Dawson disagree.

Ivan Krastev recently argued that East Central Europe’s liberals had made the error of taking an anti-nationalist stance from some point in the late 1990s. This, argued Krastev, occurred when the region’s liberals drew the lesson from the wars in the former Yugoslavia that all nationalism leads inevitably to bloodshed and violence.

By following the German example of avoiding public displays of flag-waving and treating nationalism as a creed that ‘dare not speak its name’, he claims, these liberals unwittingly forced moderate nationalists into the ‘illiberal camp’, opening the door for the illiberal backsliding that blights the region today.

This would be a compelling story – if it bore any resemblance to the actual behaviour of East Central European liberals in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

But it doesn’t. Anti-nationalism hasn’t been tried and failed in East Central Europe, it has never been tried.

In the 1990s, much as today, the most significant barrier to the realisation of an inclusive, pluralistic vision of liberal democracy was the taken-for-granted idea that the national state is the property of and instrument for titular national majorities. Both the EU and their liberal partners in Central and Eastern Europe knew this, yet both opted to accommodate ethnic nationalism at the time rather than oppose it. Read the rest of this entry »

Softly, Softly Belarus

By Lisa Walters, on 11 June 2018

Andrew Wilson, Professor in Ukrainian Studies

This speech was delivered at the European Parliament, ‘Belarus: The Voice of Civil Society’, 5 June 2018

Belarus is changing. It is changing in ways that help European engagement. But, just to be clear, the one area where change is minimal is probably where we want to see it the most, in the political sphere. The label ‘Last Dictatorship in Europe’ may be out-of-date, but Belarus is not about to become a democracy any time soon.

No, what is driving change is sovereignty. First is the logic of sovereignty, which has been operative for some time; but often belated or delayed by political factors, namely Belarus’s formerly close relationship with Russia. Second is the threat to sovereignty since the Ukraine crisis in 2014; though partly this can be traced back to the war in Georgia in 2008.

President Lukashenka’s primary motives are regime survival and personal survival. He is pushing changes for instrumental reasons. Nevertheless, these changes are significant across four main areas: cultural policy, foreign policy, security policy and economic policy. Change, as I said at the top, has been least noticeable in domestic politics. However, in order to achieve Belarus’s goals in the other areas, there is some change even there.

All of this is done slowly. But the cumulative change is great. And arguably, this may take Belarus just as far away from Russia as Ukraine in the long-run.

Poroshenko Seeks Reelection

By Lisa Walters, on 8 June 2018

Andrew Wilson, Professor in Ukrainian Studies

Ukraine is already in election year. Both the president and parliament chosen in the tumultuous year of 2014 are due to be reelected in 2019. The presidential election comes first, in March; the parliamentary elections are expected to follow in October. As always, there are rumours of some politicians plotting a different time or a different order. But, currently, the depressing prospect for the 2019 elections overall is that all of the major players will return. So none has an incentive to campaign for early elections. (Former Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk has seen his party’s support collapse, but most of his team will jump on to other parties ae ‘life rafts’).

Russia’s Global Legal Trajectories: International Law in Eurasia’s Past and Present

By Lisa Walters, on 29 May 2018

Review by Julia Klimova, PhD candidate at UCL SSEES.

On 16 and 17 of February 2018, School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES) at UCL hosted an international workshop on “Russia’s Global Legal Trajectories: International Law in Eurasia’s Past and Present”. Organized by Dr. Philippa Hetherington with generous support of the British Academy for Arts and Sciences and Pushkin House, the workshop was dedicated to the history of legal issues in Russia from the Russian Empire, Soviet Union and Russian Federation. The workshop lasted for two days and consisted of 6 panels and the total of 14 speakers. It united historians with legal scholars, which provided a rich basis for discussions of issues of legality at various points in Russian history.

Beyond Borders: Sexuality and Cold War: On Łukasz Szulc’s book ‘Transnational Homosexuals in Communist Poland: Cross-Borders Flows in Gay and Lesbian Magazines’.

By Lisa Walters, on 28 February 2018

Dr Ula Chowaniec (Impacts of Gender Discourse Series)

Transnational Homosexuals in Communist Poland: Cross-Borders Flaws in Gay and Lesbian Magazines. Pelgrave, London 2017.

The Myths, the Archives and the Impact of Community Makings

Łukasz Szulc’s Transnational Homosexuals in Communist Poland is not only about Poland and not only about Communism. It is a carefully executed study on the gay and lesbian movement in the so-called Eastern Bloc, it is a thought-provoking analysis of somehow mythical thinking of what is the “East,” and what kind of myths of the Central and Eastern Europe are particularly harmful, such as the myth of homogeneity; myth of the essence of the region; the teleological myth of good transition from communism into better kind of democracy and the right kind of ethics. Łukasz Szulc discussed all the just mentioned myths as based on one, more general myth of separation of the CEE countries from the West. Łukasz deconstructs those myths taking into account the stories of the emerging queer culture. This book is also an interesting debate on what “queer” means today and how it shapes our global identity and how those identities are used in geopolitical discourses, directly linked to the actual political decisions. The book actually starts with claiming that “we live in the age of ‘queer wars’”, where the issues of body politics, namely position on abortion, divorce and homosexuality divide the countries and people.

The First East European Mainstream Film About Lesbians History of Sexualities, Politics and Cinema under Communism in Eastern Europe

By Lisa Walters, on 28 February 2018

Dr Ula Chowaniec (Impacts of Gender Discourse Series)

The LGBT History Month, February is almost over, but it is never too late to talk about equality, justice and LGBT issues, especially in regions such as Eastern and Central Europe, where many issues, like same-sex marriage, are still to fight for. This text is based on my Lunch Hour Open Lecture, that I delivered at UCL on the 5th of December, 2017 (See below).

The Mauritian Miracle

By Lisa Walters, on 29 January 2018

By Dr Elena Nikolova, Lecturer in Economics, UCL SSEES

Both Mauritius and my hometown of Varna, Bulgaria are famous for their sandy beaches. Mauritius, for its five-star resorts on the Indian Ocean. Varna, for its breath-taking Black Sea coast. But Mauritius attracts travellers looking for luxury, while Varna (no less beautiful, by the way) – those looking for cheap sun.[1]

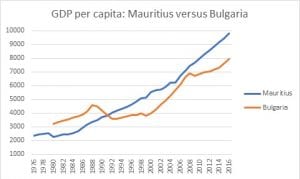

Mauritius is slightly richer than Bulgaria, but not by much. Bulgaria’s GDP per capita (in PPP terms, 2010 constant USD) in 2017 was $7, 967.70, while the corresponding figure for Mauritius is $9,822.0 (World Bank). The Mauritian government has set itself the goal of turning Mauritius in an inclusive, high-income country (with GDP per capita above $14,000) by 2030. If communist-era statistics are to be believed, Bulgaria was actually richer than Mauritius until 1990 or so. However, in recent years the gap between the two countries has widened further (Figure 1).

As of 2017, Mauritius is ranked as number 25 in the Doing Business Database, which measures the ease of doing business in a country based on indicators such as how easy it is to get electricity or resolve insolvency (as a comparison, France’s ranking is 31, behind Mauritius). By comparison, Bulgaria’s ranking is 50. Mauritius is also less corrupt than Bulgaria. Transparency International ranks Mauritius as the 50th least corrupt country in the world, while Bulgaria occupies 75th place (this comparison is based on data from 2016). And, Mauritius is a much happier place than Bulgaria: Mauritius is ranked as the 64th happiest country in the world, while Bulgaria’s ranking is 105 (out of 155 countries, 2017 World Happiness Report).

Figure 1:

Close

Close