Ukraine’s 2014: a belated 1989 or another failed 2004?

By Sean L Hanley, on 19 February 2014

Whatever their final outcome, the events in Ukraine seem likely to be of greater long-term import than the ‘Orange Revolution’ in 2004. But, asks Andrew Wilson, a long-term what?

Whatever their outcome, the events in Ukraine seem likely to be of greater long-term import than the ‘Orange Revolution’ in 2004. Ukrainians themselves are obviously debating their meaning and making comparisons with other momentous years in Ukrainian and general European history. But which year?

This is not about geopolitics: this isn’t 1939, some replay of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with two titans dividing up Eastern Europe. Russia thinks geopolitically, but the EU does not, and until fairly recently the US has been just a voice offstage. The whole point of the debacle at the Vilnius Summit was the clash between the completely different modus operandi of Russia and the EU.

There hasn’t been a proper post-Vilnius post-mortem yet (you can’t have a post-mortem till you identify the body). A technical rethink of the EU’s Eastern Partnership policy is inevitable. But the whole point is that it is too technical. As I said to the NYT, the EU took a baguette to a knife fight. The Eastern Partnership is an ‘enlargement-lite’ policy at the very moment when Russia is committed to some heavy lifting. If there is a ‘struggle over Ukraine’, as so much of the media is determined to frame it, it is clearly a very unequal struggle. Read the rest of this entry »

Slamming Sochi?

By Sean L Hanley, on 17 February 2014

Photo: kenyee BY-NC-ND 2.0

The international media’s predictable appetite for Olympic bad news stories has led to unduly negative coverage of the Sochi games, argues Valerie Pacer. However, the influence of Vladimir Putin and Russia’s ruling party still seems close at hand.

In the lead in to the Sochi Winter Olympics, much media attention has been focused on Russia’s controversial homosexual propaganda laws, environmental concerns, Russian corruption, and the composition of the national teams being sent to Sochi.

The week before the Opening Ceremony brought more negative coverage as journalists began to file Sochi-based reports. Neither has the Opening Ceremony escaped criticism. With all the coverage focusing on the negatives and less on the athletes and the events has the reporting been, as state-owned international cable channel Russia Today argued, a case of ‘see it, slam it’?

Some of the criticism has certainly been deserved, but has the coverage been overblown? As journalists began arriving in Sochi stories emerged of the non-existence of hotel lobbies, lack of door handles and uncovered manholes around the city.

But stories about the questionable colour of the tap water, although strange for Westerners, are not that unusual for a country where people who can afford it drink bottled water – and are more of a concern for Sochi residents than people who will be there for only a few weeks. The problems encountered show the difficulties of taking a city with limited modern infrastructure – and of building it into a modern Olympic calibre city in only seven years. Read the rest of this entry »

Bosnia’s protests: Made in Dayton

By Sean L Hanley, on 10 February 2014

While much media attention has focused on Ukraine, Bosnia-Herzegovina too is experiencing waves of mass protest against corruption and stagnation. The roots writes Eric Gordy lie in the unsustainable political system established at Dayton in 1995.

Conversation 1 was with the waiter in a large Sarajevo hotel, where we were generally a bit sheepish to be attending our conference (the deciding factor was that it was big enough for all of the participants, the down side was its odd business history and the fact that the main conference room was also where former Bosnian-Serb leader Radovan Karadžić liked to hold his soirees with the media). A colleague and I had heard that the employees of the hotel had not been paid for several months, so we asked. It was true, he told us.

Most of the employees had remained at the hotel through a series of ownerships and bankruptcies, and had often faced periods of reduced pay, no pay, or something in lieu of pay. So what were they working for? They wanted to keep the hotel going in the hope that one day it might become profitable again, and they wanted the employer to keep making contributions to the pension and medical care funds.

Conversation 2 was with a group of postgraduate students in Tuzla. Most of them had or were seeking work as schoolteachers. And they were only able to get short-term jobs. Why no permanent jobs in schools? Because available workplaces are distributed among the local political parties, who fill them with their members and put them on one-year contracts.

The effect of this is that no young person can get a job except through the services of a political party, and no young person can keep a job except by repeatedly demonstrating loyalty to the political party. You can probably imagine the wonderful effect this has on the development and teaching of independent, critical thinking in schools.

I could go on with vignettes. I have lots of them. But these sorts of scenes might be thought of as the background of the protests that began last week in Tuzla, developed into police violence by Thursday afternoon, and spread across Bosnia’s larger entity, the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina partly in the form of mob vandalism by Friday. Read the rest of this entry »

Unstable Platform? Poland’s ruling party struggles on

By Sean L Hanley, on 30 January 2014

Photo : PlatformaRP CC BY-ND 2.0

A series of on-going political crises in 2013 saw support for Poland’s centrist ruling party, Civic Platform, slump. Despite a number of initiatives to revive its fortunes, public hostility may have passed a tipping point argues Aleks Szczerbiak.

2013 was a year of on-going political crisis for Civic Platform (PO) party, he main governing party in Poland,. The approval ratings of both the Civic Platform-led government and prime minister and PO leader Donald Tus, slumped to their lowest levels since they came to office in 2007. A December 2013 poll by CBOS found that the number who declared themselves to be government supporters and were satisfied with Tusk as prime minister fell to 21% and 26% respectively – compared to 33% and 35% a year earlier.

Another December 2013 CBOS poll found that only 31% trusted Mr Tusk, a slump of 10% over the past year and just 1% higher than the number trusting Jarosław Kaczyński, leader of the right-wing Law and Justice party (PiS), the main opposition grouping. Civic Platform also suffered a series of local by-election defeats and has, since May, trailed Law and Justice by around 5-10% in the polls.

With the economy sluggish and unemployment remaining high, Poles have become increasingly gloomy about their future prospects. There has also been a growing sense of government drift with ministers appearing to spend too much of time on crisis management and failing to undertake long-term structural reforms. The Tusk government appeared to revert to the cautious policy of ‘small step’ reform that characterised its first term in office. This approach worked fairly well while the economy was strong but began to come unstuck when the tempo of growth slowed and unemployment increased.

Divisions and tensions within the ruling party both contributed to and were exacerbated by the sense of crisis. This reached its peak during the summer when Mr Tusk was challenged for his party leadership by Jarosław Gowin. Read the rest of this entry »

Will the West become the East?

By Sean L Hanley, on 23 January 2014

Photo: MPBecker BY-NC-ND 2.0

Politically speaking Western Europe is a far more anomalous region than Eastern Europe argues Seán Hanley. However, the ‘advanced democracies’ of the West may, soon catch-up with the fluid, elite-driven politics of the East he suggests.

“I included a dummy for Eastern Europe” the presenter said, explaining the statistical methodology in her paper.

You have, you see, to control for the unknowable, complex bundle of historical peculiarities that mark out one half of the continent’s democracies from the other and might skew your results.

“But not just a dummy for Western Europe?” my colleague and I mischievously wondered.

Silly question. of course. And we didn’t ask it. Most comparative political science research –West European democracies in the old (pre-2004) EU as their point of departure. Most political science theories and paradigms have been framed on the experience of established (or as they are sometimes termed ‘advanced’) democracies of Western Europe and the United States. Many political models, – of democracy, interest group politics or party organisation – are abstractions and distillations of the experience Western Europe.

The task of those studying Eastern and Central Europe typically been an exercise in model fitting, of noticing and measuring up the gaps – like a tailor trying to fix up a suit made for someone else with quick alterations. Eastern Europe – despite geographical and cultural proximity success of democratisation and liberal institution building – is not Western Europe.

The normative question lurking in the background is, of course, that of catch-up and convergence: when will Central and Eastern Europe become more like Western Europe? When would it consolidate ‘Western-style democracy’? Read the rest of this entry »

Discovering Dombrovsky

By Sarah J Young, on 17 January 2014

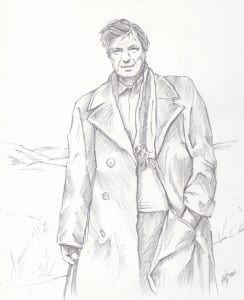

Yuri Dombrovsky by Gregory Lindsay-Smith.

© Gregory Lindsay-Smith.

Reproduced with permission of the artist.

Jekaterina Shulga reflects on the work of an extraordinary Soviet writer, Yuri Dombrovsky, and the limitations of formal literary analysis for dealing with such an unusual figure.

I remember the first time I read Yuri Dombrovsky’s novel The Keeper of Antiquities well. I was exploring writers to research for my thesis on trauma and narrative. Trauma seemed to be absent from this novel, but it had something else and I couldn’t put my finger on exactly what. And this is how Dombrovsky writes, always with a surplus, making us feel that there is forever more to it than meets the eye. That convinced me that he is one of the greatest Russian writers of the 20th century, but he has never achieved the attention or recognition he deserves. Although most Russian literature scholars will nod their heads and smile when you mention Dombrovsky, usually followed by “I really like The Keeper” or “he’s really interesting”, very few have researched or written about him. Most of what we know about Dombrovsky comes from a small number of sources and often it is based on anecdotal evidence. People want to talk about what he was like, not where he lived or what he did.

This is because Dombrovsky really was a fascinating character. He lived during the most repressive time in 20th-century Russia, and yet he remained rebellious, defiant and a lover of freedom. Born in 1909 in Moscow, he became interested in literature as a young boy, a passion would sustain him throughout his life, giving him the strength to fight for what he believed was right, even though it came at a great cost to himself. However, his righteousness was also infused with a large portion of rebelliousness and defiance. He often referred to himself as a gypsy and a hooligan. This is no Solzhenitsyn-like prophet.

In 1932, soon after starting his studies in literature he was arrested and exiled to Alma-Ata (now Almaty), where he lived until 1956. During his exile he worked at the remarkable Zenkov Cathedral, which had been turned into a museum, and taught literature and drama at various institutions. He was arrested a further three times, spent several years in the hard labour camps of Kolyma and elsewhere, and was released as an invalid. It took Dombrovsky many years to recover from these experiences, but he rarely writes about the Gulag. It is only in his poetry that we catch a glimpse of this dark period in his life. But even here there is a contrast between the terrifying subject of the camps and a light and cheerful rhythm and rhyme. Similarly, his fiction represents the darkest period of Stalin’s oppression in a surprisingly colourful and engaging manner.

His two major novels, The Keeper of Antiquities and The Faculty of Useless Knowledge, are both set in Alma-Ata and depict the life of a museum keeper working for the central Kazakhstan Museum in the Zenkov Cathedral. The novels are largely based on Dombrovsky’s life, yet they are fictional and blend his own experiences with his artistic expression. Dombrovsky suggested that some things are difficult to speak about oneself, so it seems that fiction allowed him to delve into his experiences in a deeper way. Read the rest of this entry »

Storming the Winter Palace

By Sarah J Young, on 20 December 2013

Storming the Winter Palace, a SSEES languages and culture photo competition on the theme of Russian and East European London, led students and staff to contemplate cultural resonances, contemporary identities and stereotypes – and language-learning opportunities! In the final post of the year on the SSEES Research Blog, Sarah Young introduces a selection of entries. Commentaries are by the photographers, unless otherwise stated.

Harbry Ellerby’s photograph of the Hungarian stall in Camden reminds Eszter Tarsoly that every encounter with Eastern European food in London invites us to reflect on cultural exchange, language, and translation:

The photographer took this shot in front of the Hungarian stall in Camden Town. The food on sale here, instead of the grilled sausages more usual on Polish and other East European stands, is lángos, a deep-fried flat bread whose dough is similar to that of pizza. It is traditionally seasoned with garlic and tejföl, a wide-spread diary product in Eastern Europe known in various guises in the region (e.g. Romanian smântână and Czech smetana) and most similar perhaps to soured-cream. How much a simple, hearty food – particularly recommended after a long, hearty night – can teach us about translation! The man’s silouette in front of the stall and the hanging flower baskets are revealing: the image, while entirely authentic, could have been taken only on a somewhat manicured market. This video clip of the song ’Lángos, tejföl’ by the band Kaukázus shows how lángos is enjoyed in Hungary.

Seeing a street sign commemorating one of the many Eastern European revolutionaries who lived in London during the nineteenth century, Eszter Tarsoly‘s thoughts turn to today’s immigrants:

In a quiet, respectable, yet exhilarating corner of Greenwich stretches a modest Cul-de-Sac called Kossuth Street, named after Hungary’s larger-than-life revolutionary hero, one of the driving forces behind the 1848-49 Revolution and War of Independence. Lajos Kossuth, after the demise of that Revolution, resided briefly in Britain, and legend has it that he stunned English-speaking audiences with his knowledge of English acquired in prison, or rather, with the kind of English he had acquired (only from written texts) in prison. We do not know exactly what Kossuth’s English was like. But not far from Kossuth Street, just across the Thames near Limehouse basin, there are entire blocks of flats inhabited almost exclusively by Kossuth’s contemporary compatriots, sharing overcrowded accommodation, having little hope – in the absence of knowing good English or who knows what other skills – to move on. A dead end…?

The reality of contemporary immigration from Eastern Europe is the subject of the first of two photographs by Ger Duijzings:

This image was taken during a cold night in February 2012 at just after 3 in the morning, at a bank branch opposite Victoria Station. Together with my research student Cezar Macarie I was doing a night walk around the area. Underneath a row of ‘fast, easy, and convenient’ cashpoints, in the glass protected bank area, a dozen or so Poles and Romanians are sleeping rough. As it is outside of official opening hours, the automatic door is kept open by a traffic cone. A Pole smoking a cigarette in front told us that he had been working in London for seven years, the first five years on a contract, but the last two working on-and-off.

Ger Duijzings’ second entry confronts insular British views of Europe and the question of what ‘Eastern Europe’ means in this country:

A quick snap shot taken at the end of November 2007 at Luton Airport which shows how outdoor advertising at UK airports targets low-budget travellers from East Europe. I had just returned from one of my frequent commutes to so-called ‘Eastern’ Europe which for some natives in the British isles apparently starts just across the North Sea. I took the photo from the inside of a bus waiting to take me into Central London. A lone individual is about to put his luggage into the belly of a bus: it may have been an East European guest worker or student, perhaps. The cold and grey image has the impersonal and slightly gloomy quality of what Marc Augé would call a ‘non-place’.

Stuck in transition?

By Sean L Hanley, on 20 December 2013

Photo: Photopehota CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Economic reform in Eastern Europe and the former USSR is stagnating suggests the latest Transition Report from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). However, as debates at a joint EBRD/UCL-SSEES launch event highlight, the responses needed may not be straightforward, reports Randolph Bruno.

The idea that some countries are Stuck in Transition – to take the title of the EBRD’s 2013 Transition Report – has resonated for some time in the literature. It is now it is time to take stock and ask whether transition is really over – at least for some countries.

The 2013 EBRD Transition report tries to address this by asking two main questions. Firstly, why has convergence slowed? The standard of living of the best performing countries in Eastern Europe is still around 60-70% of the average for rich Western European countries. Secondly, can economic institutions be improved if there are constraints on political reform– a question which could also be asked in a very similar fashion of Western European countries. As far as the first question is concerned, the data clearly shows an end to the productivity catch-up (moving closer to the EU average) observed at the turn of the millennium.

Why should this be the case? One possible answer is stalled political reform. The up-to- EBRD transition indicators in the Report show political reforms plateau-ing and this is worrying. The attitude of the citizens in transition states shifted in 2006-2010, basically dropping the consensus that the market economy is a good mechanism for allocating resources.

Reforms matter

However, the main element is the increase in the so called Total Factor Productivity – productivity derived from the increase in efficiency not accounted by factors of production such capital and labour. In other words, the injection of new capital or new labour has a very limited impact on productivity whereas new technology and innovation play a major role.

The EBRD downgrades of the top reformers’ rankings are concentrated in the EU countries and with the current policy convergence will slow. However, the other side of the coin is that if economic reforms are improved convergence will improve. On this point the EBRD Transition Report is very clear: keep going with reform –or re-start reform- and this can make a substantial difference. Still more worryingly, in some cases (for example in Belarus) reforms have been reversed. Read the rest of this entry »

Close

Close