FRINGE Centre blog series: ‘F’ for Fluidity

By tjmsubl, on 16 December 2015

At the launch of the FRINGE Centre on 3 December 2015, each of our core academics took possession of one letter within the FRINGE acronym, deploying the letter itself – its possible meanings and associations – as a point of departure for explaining how their own research (mis)fits within and (mis)interprets the broader FRINGE agenda. The letter F was Michał Murawski’s, whose research will result in the first core FRINGE project of the 2016-2017 academic year.

Formally, I think, the F in the FRINGE acronym stands for fluidity or flexibility. And, indeed, there is an unmistakable centrifugal sort of dynamic driving FRINGE: it’s all about the breaking down and casting asunder of disciplinary boundaries, as well as of imploding and reconfiguring tired old notions of which areas the world is divided into, and how these areas work. But F also stands for fluidity’s antonym, for firmness, for a terra firma – boundaries and borders are real: in order to break them down you need a solid, well-funded operating centre from which to launch your frontier-smashing insurgency. And I think this is what FRINGE tries to provide, a fortress for the fluxification, reconfiguration and setting on fire of frontiers. FRINGE is a fortress for fermenting, in other words, an agenda for what might be called Critical Area Studies.

Let me turn now to think about the significance of the word FRINGE itself. My own FRINGE research project is entitled “The Centre Cannot Hold? The Non-Deaths and Afterlives of the High Modernist City”. With its focus on centres rather than peripheries, this project is perhaps positioned somewhat at the fringes – or at the underside – of the FRINGE centre. The premise behind this project – which I’m carrying out together with the anthropologist Jonathan Bach of the New School in New York, and which will culminate in a conference and exhibition at the Calvert Gallery next June – is that, in some senses, and in the context of city planning at least – FRINGES are hegemonic today, and centres constitute the peripheries.

The idea of the city dominated by a soaring landmark of grand epicentre – whether a sacred temple, a secular monument or a Central Business district – was allegedly buried along with high modernity, sometime during the second half of the 20th century. The new urban age taking shape in its place – according to politicians, planners and scholars – will be humbler, more sustainable, polycentric and periphery-oriented: brownfield eco-cities instead of monumental axes or skyscraper forests; pop-up innovation hubs rather than palaces of culture; fleeting anti-statues in place of equestrian heroes and skyhigh monoliths. Or, as in the case of Moscow’s Zaryadye district, which I’m currently researching: a ‘wild urbanist’ park designed by a cutting-edge New York architectural practice, in the place of an unfinished Stalinist skyscraper and a demolished, Brezhnev-era mega-hotel.

Top-bottom: Dmitri Chechulin’s design for Zaryayde administrative building (1947); Chechulin’s Hotel Rossiya, which stood on the site between 1967 and 2006; Zaryadye Park, designed by Dillier, Scofido and Renfro, currently under construction and scheduled for completion in 2017 (images courtesy of Citymakers).

The world’s most influential planning theorists, economists and political scientists – from Jane Jacobs to Economics Nobel laureates Paul Krugman and Elinor Ostrom – have attested to and hastened the dismemberment of ‘inflexible’ and ‘authoritarian’ urban monocentricity. In its place, polycentricity (FRINGE-centricity?), equated with a more’ ‘democratic’ – more flexible – distribution of work, residence and government, has (arguably) consolidated itself as the hegemonic spatial from of late capitalist urbanism. This anti-centric political geometry coheres well with what Clifford Geertz has characterized as the long-standing ‘centrifugal impulse’ of disciplines such as anthropology. And indeed urban scholars today – not only anthropologists, but also those in neighbouring social science and humanities disciplines – are committed to rendering the ‘irreducibility’ of urban life, to analytically ‘de-centring’ the city. In effect, however, they have tended to shy away from affording descriptive prominence to urban epicentres.

But there is much evidence to suggest that epicentric spaces continue to radiate over the – mundane and extraordinary – everyday lives of cities and their inhabitants; and to act as pivotal points for processes with city-wide, regional, national and supra-national resonances. The ancient epicentres of Moscow, Mexico City, Mecca, Beijing, Jerusalem or Athens reign uncontested as terrains of sacred and symbolic concentration (even if, as in Mecca, their physical make-up has been radically altered). Many planned epicentric spaces from the 19th and 20th centuries – in Cairo, Kiev, Kharkiv, Istanbul or Brasilia – have been the sites for a dramatic burgeoning of urban protest during the past half-decade. Landmark structures and ensembles inherited by new regimes from old ones in cities like Bucharest, Berlin and Warsaw – where the unmaking of political economies and ideological cosmoses is manifested with accentuated clarity – serve as readymade ideal types for transitologists.

What is more, axial avenues and gargantuan landmarks are being raised today with no less flair and frequency than during the Haussmanian late-19th century and high- modernist mid-20th. Amid reconstituted Prussian castles, relocated Asian capitals, post-socialist sacred complexes, central African tech-hubs and Chinese eco-cities, myriad political geometries are at work: de-centralizing rhetoric mingles with despotic decisionmaking, axial symmetry with speculative financing.

The inevitability – and the desirability – of this centrifugal march towards the FRINGE city, is something, which our project would like to look critically at. We’d like to highlight the powerful role that broadly-conceived centrality and monumentality – in the political and economic as well as aesthetic sense – continue to play in the cities of today. The goal of my project, then, is to hijack the FRINGE Centre, to re-CENTRE the city.

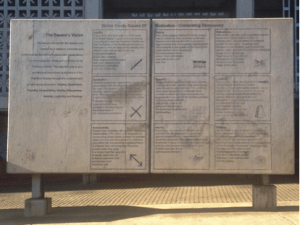

Centralities under Investigation (from top-bottom): Completed in 2014, the Abraj Al-Bait Towers envelop the Masjid al-Haram and Ka’aba in Makkah, Islam’s holiest site (completed in 2014). Photo credit: WikiMedia Commons; the Euro-Maidan protests during the winter of 2013-2014 were centred on Kiev’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti, the culminatory point of the Stalin-era architectural ensemble, which constitutes the social and symbolic core of the Ukrainian capital. Photo credit: spoilt.exile, via a Creative Commons license; The Radiating Palace: Nine Rays of Light in the Sky by Henryk Stażewski (1894-1988), curated by the Museum of Modern Art in the Świętokrzyski Park adjacent to Warsaw’s Stalin-era Palace of Culture and Science, in November 2009. In the words of one of the curators, this project ‘marked the territory’ for the new building and institution in the vicinity of the Palace. But ‘it was done slightly off centre, we didn’t want these rays marking the centrality of the Palace, this symbolism.’ Photograph by Jan Smaga, courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw; the monumental axis at the heart of Astana, the post-1991 capital of Kazakhstan, a neo-Baroque project masterplanned by Japanese metabolist architect Kisho Kurokawa, featuring megastructures designed by global starchitects (including no less than two separate pyramids designed by Norman Foster). Photo credit: Google Earth creative commons license; the Romanian People’s Salvation Cathedral in Bucharest, currently under construction within the site of the neo-Stalinist House of the Republic, whose construction was launched by Nicolae Caesescu in 1984. Photo credit: Miral.Mihai, licensed under a WikiMedia Creative Commons License; a plaque at the Walter Sisulu Square of Dedication in Kliptown, Johannesburg – a neo-modernist ceremonial ensemble built in 2005 to commemorate the 1955 signing of the anti-apartheid Freedom Charter – painstakingly explaining the politics of the complex geometrical symbolism built into the Square’s architectural fabric.

Michał Murawski is Mellon Post-Doctoral Fellow at UCL SSEES

Note: This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the SSEES Research blog, nor of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, nor of UCL.

Close

Close