Nazi storm-troopers’ cigarettes

By Sarah J Young, on 11 September 2013

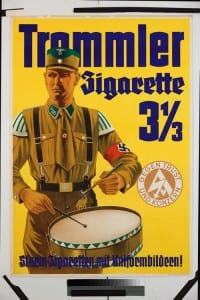

Marketing the Storm troopers’

cigarettes (Image reproduced

by kind permission of the Münchner

Stadtmuseum, P C 13/70)

Cigarette marketing in the inter-war period opens up a new angle on Nazi history, finds Daniel Siemens.

Smoking cigarettes became a mass phenomenon during and shortly after World War I. No longer associated exclusively with oriental luxury, smoking nevertheless marked differences – of regional provenance, social class and also of political orientation. In 1926, the cigarette pack was successfully introduced in Germany.

This innovation not only resulted in a boost sales, it also allowed for a new form of marketing. The rectangular boxes proved to be an ideal place for graphic illustrations that helped to identify specific cigarette brands. The marketing of some brands soon reacted to the actual political, social or economic situation. Between 1930 and 1932, in a period of rapidly rising unemployment figures in Germany, these advertisements sometimes used drastic images of emergencies, such as a traffic accident or a shipwreck. It suggested that the smoker of these particular brands reacted serenely and composedly in the face of such situations – coolness desperately sought after by millions of Germans confronted with personal economic ruin, often accompanied by family ruptures.

The late 1920s were the ‘Kampfzeit [time of struggle] of the cigarette market’ – not a direct allusion to Nazi terminology, but a contemporary wording used by the market players. Technological invention and the breakthrough of modern marketing techniques in Weimar Germany forced the cigarette companies into fierce competition. It was precisely in this period, in 1929, that a certain Arthur Dressler approached the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) and its Sturmabteilung (Storm Troopers, the SA) with his plans for a new cigarette factory in Dresden. The Saxon capital had been one of the centres of the cigarette industry in Germany since the late 19th century.

The late 1920s were a remarkable time for a start-up enterprise in this already largely saturated industry, all the more so as Dressler lacked the considerable means necessary for such an investment. But Dressler, an NSDAP Party member, had an interesting idea: he suggested producing a home brand SA cigarette. If the SA would be willing to pressurize their men into consuming his new brand exclusively, he promised the militia a reward of about 15 to 20 Pfennig for every 1000 cigarettes sold. The SA leadership in Munich approved the plan, and with the help of a successful Dresden businessman the ‘Cigarettenfabrik Dressler Kommanditgesellschaft’, better known under the name of her major brand ‘Sturm’, was established.

There was indeed money to be made by the storm troopers’ smoking habits. Already in 1930, Dressler is said to have paid monthly contributions to SA chief of staff Ernst Röhm and some regional SA leaders. The success story continued in subsequent years, as the findings of Thomas Grosche, a young historian from Dresden, reveal with striking clarity: according to the balances for 1932, the company generated a turnover of more than 36 million reichsmark. Most of the money was reinvested for the acquisition of new buildings and factories, and a considerable sum was spent on publicity in magazines and newspapers, by the company-owned loudspeaker van and even for hiring advertisement planes. However, the owners as well as the SA made a considerable profit in 1932, and an even greater one in 1933.

This financial success story was not only achieved because of a smart business model. It was also – as so often with the SA – built on violence. This violence was directed against the regular SA men as well as business rivals. With the start of the Sturm factory, storm troopers were not simply targeted in the relevant Nazi media with encouragements to buy only the new cigarettes. The SA leaders even formally forbade them to buy different brands. To make sure their orders were obeyed, they engaged in bag searches and imposed fines in case of storm troopers’ disobedience.

The only consumer choice sanctioned by the Party was among the different brands offered by the Sturm company: the well-to-do storm trooper could buy the relatively expensive ‘Neue Front’ [New Front] or some slightly cheaper cigarettes sold under the name ‘Sturm’ [storm]. Most SA men, however, preferred the cheapest brands available: ‘Alarm’, ‘Balilla’ and ‘Trommler’. The latter brand was by far the most successful: in 1932, Trommler sales contributed more than 80 per cent of the company’s volume of sales, and in the following year, 95 per cent. These figures aptly mirrored the economic and social crisis in Germany.

Dressler speculated that by agitating against his rivals, he would be able to conserve advertisement costs that usually accounted for a great share of the cigarette industries’ turnover. When the Nazis came to power, in 1933, storm troopers closely associated with the Sturm company organised boycott actions against competing cigarette producers. Such actions also increasingly affected Philipp F. Reemtsma, the head of Germany’s biggest cigarette corporation, in Hamburg. Storm troopers now repeatedly attacked cigarette dealers who sold Reemtsma products, smashed shop windows and even physically attacked those who worked in such places, thus giving the term ‘Kampfzeit of the cigarette market’ an even more literal meaning.

However, such violence quickly backfired. Reemtsma was not willing to let the Brownshirts ruin his business. The fact that the Nazis had initiated proceedings against him because of alleged corruption furthermore demanded immediate action. Between August 1933 and January 1934, Reemtsma repeatedly discussed his and his company’s problems with Hermann Göring who, as Minister of the Interior for Prussia, was in an ideal situation to exercise power over the SA. Göring’s ‘goodwill’ was available, albeit not cheap: Reemtsma had to donate the very high amount of three million reichsmark, officially for the preservation of German forests and their wildlife stock as well as for state theatres in Germany. In return, Göring made sure that the criminal investigations against Reemtsma, the anti-Reemtsma publicity in the Nazi press and the SA boycott actions stopped. This spelt doom for the Sturm company, which was also negatively affected by the SA’s fall from power after the Night of the Long Knives in the summer of 1934. No longer protected by the Nazi party, it filed for bankruptcy in 1935.

Daniel Siemens is DAAD Francis L. Carsten Lecturer in Modern German History at UCL-SSEES. His work covers 19th and 20th-century Europe and the United States, with a particular emphasis on the interwar years. He is the author of several books, most recently: The Making of a Nazi Hero. The Murder and Myth of Horst Wessel (I.B. Tauris: London, 2013).

The article above is a sketch of a more detailed analysis to be included in his next monograph, which will be a complete history of the National Socialist Storm troopers (SA), scheduled for publication with Yale University Press in the not too distant future. For more information on Daniel’s publications click here or here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the SSEES Research blog, nor of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, nor of UCL.

One Response to “Nazi storm-troopers’ cigarettes”

- 1

Close

Close

[…] and big business in interwar Germany over at the UCL SSEES Research Blog, where his post about Nazi storm-troopers’ cigarettes discussed the rise and fall of Arthur Dressler’s ‘Sturm’ company, which made a handsome […]