Behind Putin’s Self-imposed Food Ban

By Borimir S Totev, on 7 April 2015

By Enrico Cattabiani

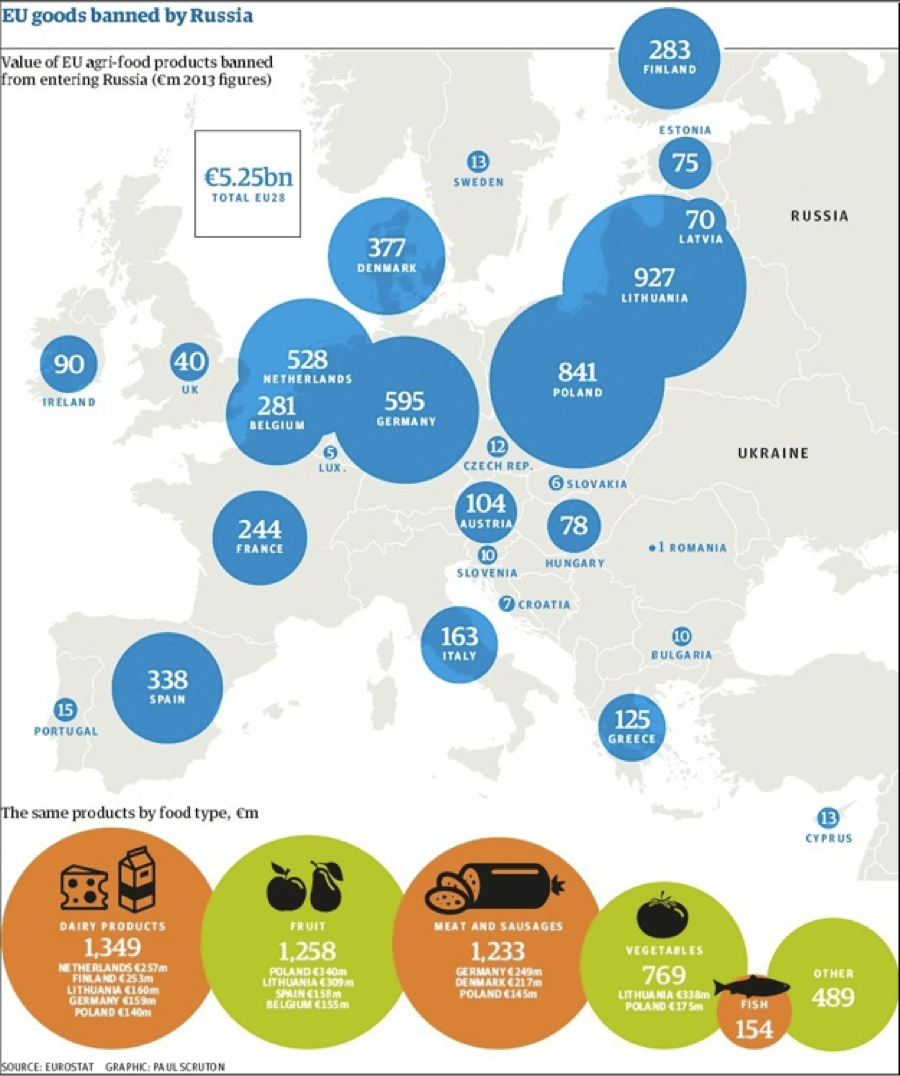

On August 4 last year, Vladimir Putin responded to the latest round of sanctions levied against his regime by imposing a ban on the import of food products from the EU, the US, and their supporters. The disruption of commerce was worth approximately $12 billion to the Russian economy, with secondary effects in the targeted countries, particularly the EU, causing unemployment within the agricultural sector, a slump in the price of the banned foods in domestic markets, and great losses for producers.

At the same time, Russia saw a dramatic rise in food prices, empty shelves in shops, restaurants obliged to change their menus and a revival of the old-fashioned black market, all as a consequence of the ban. Western media has been harshly critical of Putin’s policy, calling it a desperate and useless retaliation done simply for the hell of it. The ban, they argue, is a boomerang that will come back to hit Russia hardest.

There are two very good reasons why this might be true. First, sanctions are a political tool used to force a rival to alter its behavior. In this case, although affected parties in the West are pressing their governments to lift sanctions, damage to the wider European economies has been limited, and the voices of agricultural producers are not strong enough to force a change in policy.

Second, restrictions on trade are usually harmful for any economy, and Russia is no exception. Although it could eventually be beneficial for some sectors, scarcity of products and rising inflation have predictable and undesirable effects on a large segment of the population. Therefore, the ban on food appears to be ineffective in the first instance and counterproductive in the second one.

Why, then, has Putin opted for such an irrational policy? Didn’t he have any alternatives to imposing sanctions – and why food, rather than something else? Before asserting that the ban has been a total failure, however, we must analyze the situation from the Russian president’s perspective.

Why Putin needed to act

Two main political calculations pushed Putin to adopt sanctions. First, to be considered a superpower a country must act like a superpower, and that is certainly the status that Putin seeks for Russia. When the sanctions hit, Russia had to show its muscles and hit back. This is even more the case considering sanctions were imposed in response to Russia’s undeniable involvement in Crimea – which Putin has always denied.

The second reason is purely domestic and concerns the fact that many Russians, thanks to state-led propaganda, perceive the escalation of the Ukraine conflict as the result of Western interference in support of a fascist, anti-Russian coup. Putin’s approval rating rocketed up at the beginning of the turmoil in Crimea, and he has had to keep playing the part of the strongman to maintain credibility at home.

The logic of sanctions: trade-offs, elites, and money

The decision of whether to adopt a particular programme of sanctions is generally made with an eye on the damage, both economic and political, and consequent backlash that they are likely to provoke. In other words, political leaders choose sanctions regimes that maximize damage to its targets and minimize repercussions for their own state or power base.

If we accept that the most important goal of every leader is to remain in power, it follows that, in democratic countries, reducing the impact of sanctions on one’s own economy is essential. Indeed, popular support is necessary to be re-elected, and damaging consumers and businesses for political reasons would likely lead to electoral defeat. This logic has been called the ‘enforcement dilemma’ and expresses the trade-off for the political elite of imposing sanctions.

However, such logic works in a different way in non-democratic countries. Here, to remain in power an authoritarian leader must guarantee a constant flow of money to his inner circle, upon whom he relies for support. In this case, the trade-off is dictated by the need to avoid losses for the elites, disregarding the fallout for the population at large, unless widespread unrest or civil disobedience makes them impossible to ignore.

Such considerations partially explain why Western sanctions have targeted individuals and sectors related to Russian’s elites while Russia has targeted ground-level economic activities in the West.

As such, the repercussions on Western governments of their own sanctions have been manageable, since only a very small fraction of their economies, mostly oil and gas multinationals, have been prevented from trading with Russia. Likewise, Russia’s sanctions haven’t damaged crucial sectors related to the elites’ businesses, nor have they triggered protests or revolts. This may indicate that Putin opted for the solution that caused the least suffering from his own perspective, implying that he acted with absolute (authoritarian) pragmatism.

Behind the choice of banning food

Food is a replaceable good. Russia imports most of it from Western countries. Food is not linked to Putin’s friends’ interests. By bearing in mind these three considerations and by understanding the starting conditions of Russian’s economy, we can put ourselves in Putin’s shoes and understand why he chose to target food imports.

The fall in value of the ruble has led to more expensive imports for Russian firms and to a consequent worsening of the balance of payments. Cutting $12 billion of imports of a replaceable good could help curb Russian dependence on Western countries and slightly alleviate the ruble’s decline. This is not properly orthodox from an economic point of view, for the obvious reasons of rising inflation and widespread shortages, but in Putin’s logic, that $12 billion could also be reinvested and spent elsewhere, which is his declared goal. Where?

The first candidate is obviously the internal market, which can provide goods on the cheap. Second, and more important, are the other BRICS (Brazil, India, China and South Africa) and the countries of Central Asia, with whom a great number of new supply contracts have been signed in recent months. This has contributed to a diversification of Russia’s international trade patterns, which will have further consequences in the long run.

Yet, both the slow pace of transitioning to new suppliers and the inadequacy of local industry in meeting internal demand, as evidenced by the current shortages, demonstrates that not all that money has been spent. Part has been invested in industry, while some may simply have been diverted to other goods.

Losers and winners

Looking at the ban from a broader perspective, consumers, obviously, have been the main losers. Not only do they have access to a much lower quality of food, but they also face the daily uncertainty of sudden price increases. More dramatically, it could also be argued that Putin, conscious of his approval rating and of ordinary Russians’ paranoia about inflation, has played on their fears to trigger a ‘run on food’, letting consumption accelerate in a problematic macroeconomic environment.

This is plainly unsustainable in the long run, but a crucial point, which many critics seem to have forgotten, is that the food ban will – or at least, should – end in August this year. Food prices may gradually return to normal once trade patterns with Western economies are reestablished.

Yet, nothing will be as it was before. Russia’s internal market will have developed, maybe not enough to compete with the EU and the US, but certainly considerably. Many new supply relationships will have been established with countries in the rest of the world. Restaurants may not necessarily revert to their pre-ban menus: people’s tastes are impossible to predict, but who is to say that Russian consumers might not have acquired a taste for cheaper foreign cuisine (Chinese?). All these factors might keep the demand for Western products low.

From a broader geopolitical perspective, Russia’s dependency on Western countries will be further reduced, which is line with Putin’s goals. Moreover, the events in Crimea have accelerated a process that has seen emerging powers try to carve out a bigger role on the international stage by banding together, both in political and economic terms. The disruption of the food trade undoubtedly represents another front in this battle.

August is coming. Conclusions may then be drawn. We will see whether one year of the food ban will have been enough to signal a further step away from Western dependence. More importantly, we will be able to determine whether the suffering of Russia’s population in the short term will result in long-term gains for President Putin. If not, we will be free to criticize his decision to ban Parmesan cheese and other delicacies from Russians’ tables and to reflect on the consequences of a failed policy of economic brinkmanship.

Enrico Cattabiani is on the first year of the IMESS double-degree Masters programme at SSEES, studying Economics and International Relations. From next September, he will study at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, where he is planning to write a thesis addressing some of the questions left unanswered in this article.

Close

Close