‘The papers had been taken from Room 8 and lodged on the floor of the room at the east of the Slade. I remember looking at them in dismay, making a drawing of the heap of boxes, discarded portable typewriter and [a] sculptured head never collected by a student. Their shelves had been removed from the Office, most of the books and pamphlets had gone to the College Library, and personal records were under the main stairs …

There were also collections of photographs, personal depositions, but no artwork at all. I began to ask for material from old students to augment the holdings. Shelving was bought and an order made among the disintegrating boxes. I asked Ian [Tregarthen Jenkin] to come to see. Did my order in any way replicate his former, working order? He took a quick look, smiled; said ‘You’re doing a great job!’, and left. At that point I realised that an archivist is there to make decisions: no one else much minds what happens, apart from obtaining a quick answer to their question.’ (Stephen Chaplin, Slade Archive Reader, UCL Special Collections MS ADD 400, p. 14)

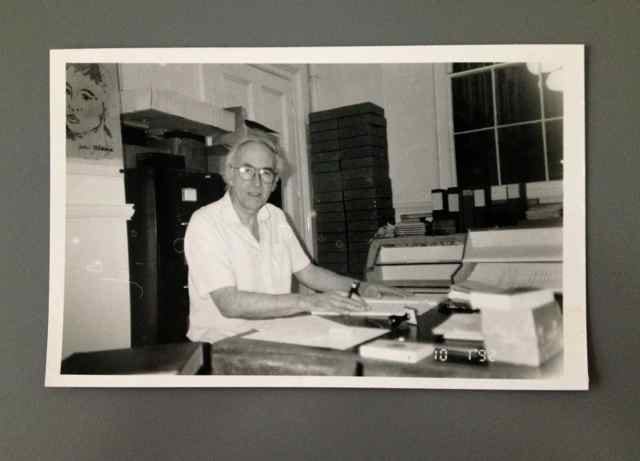

From 1990-97, scholar and former Slade student Stephen Chaplin undertook an ambitious project to rescue the Slade archives. Chaplin began to catalogue and re-house the collection of documents, photographs and objects, which up to that point had been dispersed in unsorted boxes in back corners of offices, studio spaces and family archives. On the advice of Jean Spencer, then Tutor to the Students & Slade Secretary, he also set out to ‘computerise’ these archive records – though the limitations of the early electronic catalogue systems would prove to cause as many challenges as solutions.

As a retired art historian and Slade alumnus (1952-55), Chaplin also used oral history as a way of capturing the everyday experiences of those at the Slade. He conducted audio interviews and sought contributions to the archive from alumni and their families in the form of letters, memoirs, photographs and other documentation. He faithfully answered scholars’ research queries and noted and logged the who, what, where and when of as much Slade history as he could gather. During these years, he kept a personal diary to document his observations of ‘the daily life of the school as seen though the marginal vision of an archivist’.

With funding from the Leverhulme Trust and ongoing support from UCL Library and UCL Art Museum (then known as the Strang Print Room), Chaplin’s work provided an invaluable foundation on which to build a framework for the Slade’s growing archive. But technological challenges and finite resources limited his ambitions. The computer system crashed at a key moment and some of the index was lost. It was too early for the internet to be of much help in drawing the networks of connections between living and written history, and the mass of information gathered could not be encompassed in publishable form without significant editorial support. Chaplin’s contribution rests in large part as an unpublished manuscript and archive index that he called ‘the Slade Archive Reader’, now housed in UCL Special Collections [MS ADD 400]. The document provides an invaluable overview of the archive, functioning as both a finding aid and a summary of the first century of the school’s history.

Close

Close