10 Questions

By ucqndko, on 5 December 2014

An interview in 10 Questions…

In this monthly feature, the Institute of Biomedical Engineering (IBME) interviews our researchers, academics, students, clinicians, affiliates and partners to find out a little more about who they are and what they do.

This month the IBME interviewed Dr Ben Hanson, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, UCL

1. What is your job title?

Senior Lecturer & Departmental Tutor

2. How long have you worked as a Senior Lecturer & Departmental Tutor?

Nine years as a Lecturer, appointed as Departmental Tutor last year.

3. What keywords would you pick to describe your work?

Biomechanics, signal processing.

4. What is your favourite thing about your work?

Solving problems, that’s what engineering is all about. It’s lovely to work in hospitals, and with inspiring people who make a real difference to people’s lives. We’re doing a great project at the moment showing scary movies to people with implanted pacemakers in an attempt to identify how stress affects the heart. [UCL News; Time Magazine]

5. What’s been your career highlight?

My first publication in a medical research journal, (Circulation, 2009). That took a lot of hard work and head-scratching, but my struggle to understand the workings of the heart and to make sense of some data we’d recorded turned out to be really useful in revealing how things worked at a fundamental level.

6. What is your favourite quote?

Miss Piggy: “Never eat more than you can lift” (a great image and, I guess, a lesson in biomechanics).

7. Who has been your greatest mentor and why?

My first PhD supervisor, Andy Plummer, who is such a nice human being as well as being an engineering genius: he demonstrated that the two are compatible.

8. What do you do in your spare time?

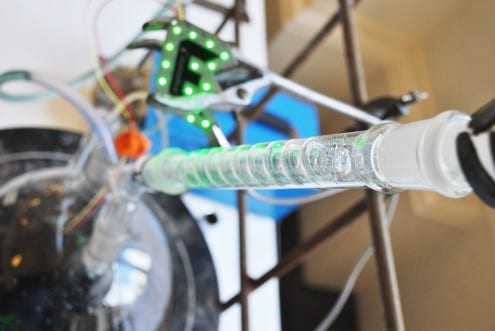

Eat! Often with friends & family, often something I’ve made: I am a chocoholic and like making chocolates. My research involves the biomechanics of eating and drinking for people who have difficulties, e.g. due to a stroke, surgery or dementia. I’m very motivated to find ways to control the mechanical properties of foods & drinks to make them easier to manage so that I can continue to enjoy my food when I’m old & frail.

9. What’s your favourite book at the moment?

I was laughing out loud at “The hundred-year-old man who climbed out of the window and disappeared”.

10. If you had a superpower, what would it be and why?

I love it when the clocks go back and you have an extra hour in the day so I would have an extra hour please, then I might get to do some of the things that unfortunately get squeezed out.

Dr Ben Hanson is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at University College London, with Affiliate status in the Division of Medicine. Dr Hanson researches biomedical applications of engineering, system-modelling and analysis.

Close

Close