Lamp Black: Digital Humanities

By Ruth Siddall, on 26 August 2016

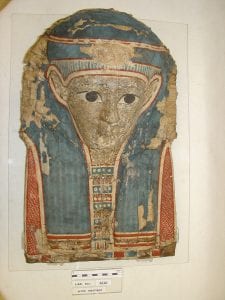

We are all familiar with the colourful coffins and mummy cases associated with Ancient Egypt. These artefacts can tell us much about the life and death of the person but unintentionally, they have even more to reveal about life in Ancient Egypt. Coffins were made in large numbers in specialist workshops. Some were expensive and intended for the elite of society and were made from fine materials by the finest craftspeople. Others were for the less well-off and often recycled material from other coffins and items of waste. Most coffins were made of painted wood, but many funerary masks and mummy cases were made from a composite material known as cartonnage. We can think of this as something akin to papier mâché, but made from layers of papyrus or linen, glued together with animal skin glue and a paste know as whiting, made from pulverised chalk mixed with glue.

Above: Cartonnage masks UC45851 & UC45847 from UCL’s Petrie Museum, made from layering and moulding papyri and whiting and then painted.

We often think of writing in Ancient Egypt being all about scribes employing masons to cut intricate hieroglyphs for monumental inscriptions on obelisks or temple pylons, however a huge amount of letters, lists, legal documents and so on were written in ink on papyrus, and these are less likely to have been preserved in the archaeological record. However some of these documents were recycled and used to make cartonnage and so were, by serendipity preserved. By reading them we could discover a wealth of detail about everyday life in Ancient Egypt … but we would have to destroy the mummy case first! We need a method of being able to read these invisible texts which is non-destructive.

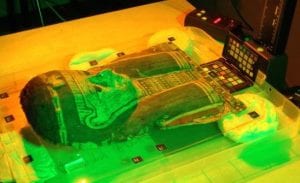

With modern imaging technology and processing it is looking like there is another way. I spoke to Dr Kathryn Piquette of UCL Centre for Digital Humanities; a cross-faculty research centre in the UCL Department of Information Studies. Kathryn, an Egyptologist who has a PhD in the development of writing and art, is perfectly placed to be one of the collaborators working on the project Deep Imaging Mummy Cases. This has been set up as a consortium between research institutions in the US and in Europe under the direction of Prof. Melissa Terras and Prof. Adam Gibson at UCL.

Kathryn’s work is all about trying to detect the ink hidden in layers of cartonnage as a first step towards evaluating the potential of multispectral imaging to visualise ink on papyri within cartonnage

Multispectral imaging uses light waves at wavelengths outside human vision, primarily in the infra red (IR) and ultraviolet (UV) spectrum, used in both reflectance and excitation mode. Whether you can see the ink or not depends on the light source and pigment used. Light can be filtered before it hits the camera’s sensor. A series or ‘stack’ of images are produced using different wavelengths and types of filters. The image stack can be analysed and tweaked using processing software to enhance the contrast of the writing inks against the papyrus. Different inks produce different levels of contrast.

Above: imaging cartonnage under different light sources

Carbon-based ink such as lamp black absorbs IR radiation. Therefore it is very obvious when viewed using IR light and has a good contrast with the papyrus substrate. Lamp black was the main type of ink ingredient used for writing on papyrus in Ancient Egypt. Red inks made from ochre or the arsenic sulphide mineral realgar were also used, and iron gall inks were introduced into Egypt from the northern Mediterranean during the Ptolemaic period (305 BC – 30 BC).

Kathryn is testing the power of multispectral imaging on papyrus using surrogates for cartonnage which she calls ‘phantoms’. These are made of layers of modern papyrus affixed together. Marks in ink are made on the surface, one layer, two layers and three layers down. The aim of the phantoms is to find out how deeply the wavelengths from different light sources penetrate the papyrus. Can the subsurface marks be revealed?

She is testing this method using replica lamp black ink, red iron oxide ink, iron gall ink and modern Winsor & Newton India Ink. Our very own Jo Volley, PI of The Pigment Timeline Project assisted Kathryn in making the iron gall ink from oak galls.

Kathryn tells me that these phantoms were surprisingly difficult and fiddly to make because papyrus sheets have the tendency to curl. To create a flat surface, with no air pockets between the layers of papyrus, she had alternate the direction of the sheets so facing fibres ran in opposite direction and then stitch the layers together using linen thread.

Above: Kathryn’s ‘phantoms’ for testing the imaging of different inks.

This is a pilot project. So far Kathryn has discovered that presence carbon ink can be observed down to the third layer but actual legibility may not be feasible beyond the second layer; iron gall and red ochre inks are less easy to detect. Other members of the team have tested the efficacy of Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and various X-ray techniques final assessment of results now underway.

It is hoped that a follow-on a project will enable further refinement of non-destructive techniques and development of protocols for imaging papyri in cartonnage as well as documentation of their internal structure.. These techniques are unlikely to become affordable and routine in the near future, but there is lots of scope to learn more about pigments and their properties under different light sources and to further refine this technique to enable us to access this hidden wealth of ancient writing.

Lamp Black is a form of carbon black. It is essentially soot and is composed of finely particulate amorphous carbon. The pigment is cheap and easy to make; all you need is a flame and a fuel source and a surface for the soot to accumulate on. This pigment must have been recognised from the earliest dates of human cognition. It has been recognised in paintings of all periods and all regions and was also widely used as a cosmetic and as a tattooing ink. Lamp Black has been the main ink used for writing and calligraphy in many cultures (although iron gall inks and sepia have also been used from the Roman Periods onwards). Nevertheless, Lamp Black was the main constituent of India Ink (but note that modern India Inks are made with a mixture of organic dyes).

Above: Aggregates of lamp black particles made by Ruth Siddall from a soya wax candle flame and observed under plane polarised light at x 1000 magnification.

The best lamp blacks are made from burning tree resins, pitch or tar, or burning the wood of resinous trees such as pine. Burned gum from Kauri pines was used to make tattooing inks by the New Zealand Maori. Pine resin or pine logs were used in China and Li Qiaoping describes a variety of complex kilns constructed for lamp black manufacture, whereby the chimneys were fitted with a vessel for collecting the soot, which was then removed and collected using a feather duster.

The universally accepted method of removing the lamp black from the surface seems to be by scraping it off with a feather. In addition to Li Qiaoping’s descriptions, Jacobean gentleman Henry Peacham wrote in his treatise ‘The Gentleman’s Exercise’ (1612; left) ‘The making of ordinary Lamp blacke. Take a torch or linke, and hold it under the bottome of a latten basen, and as it groweth to be furd and blacke within, strike it with a feather into some shell or other, and grinde it with gumme water.”

The universally accepted method of removing the lamp black from the surface seems to be by scraping it off with a feather. In addition to Li Qiaoping’s descriptions, Jacobean gentleman Henry Peacham wrote in his treatise ‘The Gentleman’s Exercise’ (1612; left) ‘The making of ordinary Lamp blacke. Take a torch or linke, and hold it under the bottome of a latten basen, and as it groweth to be furd and blacke within, strike it with a feather into some shell or other, and grinde it with gumme water.”

M. Watin writing at the end of the 18th Century suggests burning pitch in a closed shed with sheepskins hung from the rafters. The soot collects in the fleece and can then be shaken out. This sounds like a dirty job, but would have produced soot on an industrial scale. It should also be noted, that if you have access to a shed, you are well set to begin the manufacture of a wide range of pigments … lead white, verdigris, vermillion … but I digress.

To make ink, as we have learned from Peacham, the soot needs to be mixed with water and a gum so that it sticks to the writing surface. Such gums would have been gum Arabic (used as the medium in watercolour paints) as well as gum mastic, gum tragacanth and shellac; the latter a resin secreted by insects, the lac bug (Kerria lacca).

Some blacks are blacker than others; below is a screen print by Onya McCausland and Jo Volley of UCL’s Slade School of Fine Art called ‘Ivory Lamp Mars Bone Vine’ using different black pigments. With the exception of Mars Black which is an iron oxide, the others are all carbon blacks; soots or chars. ‘Blackness’ depends on factors including particle size and the degree of reflectivity/absorption of light. Ivory black has always had the reputation as the finest of black pigments, but lamp black is readily available, inexpensive and easy to make and is a fine, black ink.

References

Li Qiaoping, 1948, The Chemical Arts of Old China, Journal of Chemical Education, 215 pp.

Visit UCL’s Petrie Museum to see examples of Egyptian cartonnage mummy masks and cases.

Close

Close