Morland’s Blue; UCL Arena Centre

By Ruth Siddall, on 19 March 2017

Senior teaching fellow in UCL’s Arena Centre for Research-based Education, Nick Grindle, started academic life as a Art Historian. Nick has been with The Arena Centre (formerly CALT) since 2011 and has responsibility for educational development within UCL’s Social and Historical Sciences and Arts and Humanities Faculties. However, UCL being the wonderful place it is, Nick still has opportunities to teach and conduct research within UCL Art History, the department where he studied for both his undergraduate and PhD degrees. One of his main interests is in the 18th Century English painter, George Morland and he has recently curated an exhibition of this artist’s works at the Stanley and Audrey Burton Gallery, at the University of Leeds. In our Pigment Timeline Questionnaire, Nick responded on behalf of CALT, stating his general interest in colour theory and pigments and mentioned an especial interest in the palettes of 18th Century British painters. Initially I was concerned that we may be returning to the murkier ends of the spectrum for this blog, envisioning browns and dull greens. But Nick has contributed some more cheerful colour via the subject of his research, Morland.

George Morland (1763-1804) spent most of his short life in Fitzrovia and Camden. He was apprenticed to his father, who gave him ‘a very complete colour box’ (Collins, 1806). From the late 1780s he was a popular society painter and got rich quick as a consequence. He fuelled a fast lifestyle with colossal debts, and died in poverty aged forty-one. Nevertheless as a painter, his output was prolific, with a specialism in genres scenes of both high London society and rural labour.

I met with Nick to talk about Morland’s painting techniques, palette and subjects. Nick tells me that there were a number of contemporary biographies of Morland, which alluded to his rapid painting technique and dealings with colourmen. One of his biographers discussed his use of colour as follows:

‘Morland was always particularly careful to use the best oils and most durable colours; concerning the chemical properties of which he possessed a considerable degree of practical knowledge, chiefly derived from his father, who had studied the subject with great attention, and made many experiments. Morland’s skill in these matters is best evinced by the high state of preservation in which even his earliest paintings still remain, for they have experienced no change but the addition of that mellowness, which no art can emulate, and time alone can give. He maintained that every possible effect might be produced with four or five colours, and that the ochres were sufficiently brilliant for the strongest lights; he however occasionally employed Naples yellow. In rich parts he used the umbers and Vandyke brown, never asphaltum, and copies are sometimes detected from this circumstance; for the presence of that substance may easily be discovered by passing a wet finger over it, since the moisture will lie evenly upon the other parts, while it recedes from the greasy surface of the asphaltum rising in ridges like net-work.

‘His principles were few and obvious, though for the most part just, such as that a portion of pure red should be introduced somewhere in a picture; accordingly we never see a landscape of his without a red cloak, coat, or cap; and this is uniformly accompanied by a blue jacket, or petticoat: he also remarked that there should always be a touch of vermillion in the lips, though they should not be painted entirely with it.

George Morland, The Old Water Mill, 1790, oil on canvas, 100 x 125 cm, Yale Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

‘Of his mode of procedure, in general his method in painting trees will serve as an example. He used to lay in the branches, in a broad style, with simple cool tints of ochre and blue, or black; and after the dead colour was dry, to glaze them with yellow lake, or brown pink, and to touch in the lights with ochre, or Naples yellow, pure or tinged with blue, and sometimes mixed with yellow lake. He occasionally used the softener, but always touched upon his painting afterward: sometimes he would varnish the picture, and drag, or otherwise work upon it while tackey [sic].

‘Among other subjects connected with art, at present in a very imperfect state, from the want of accurate experiments, is that of the properties of colours with respect to durability. Thus artists often waste their time in making fruitless enquiries of each other, and in collecting accounts which agree in nothing but their uncertainty, and each is at last reduced to find out by hasty and imperfect trials, during his own short life, the best mode of transmitting his works to posterity. (Dawe, 219-221).

Indeed, Nick told me that during his research, he has visited many a British provincial museum to see Morland’s paintings in storage. All have been in very good condition with little evidence for previous restoration or lining the canvas. This is rare indeed for paintings of this period.

Looking through images of Morland’s paintings in public collections via the Art UK website and also in the collections of Tate and the Yale Centre for British Art we get a sense of his palette, and we see just how well Dawe has described Morland’s use of colour. The outdoor settings of many of his paintings dictate a range of greens, yellows and drab browns, and there is often a splash of colour in the foreground or in the clothing of staffage; a woman with a blue parasol or shawl, a man with red breeches, a blue cart outside a barn.

George Morland, The Angler’s Repast, 1789, oil on canvas, 63 x 76 cm. Yale Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

A late work by Morland ‘The Artist in his Studio and His Man Gibbs’ is in the Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery and can give us some clues to his painting practice (below). This self portrait was created towards the end of Morland’s life, c. 1802, when the artist had clearly fallen on hard times, indeed he had recently been released from debtors’ prison. His dingy, dark studio is clearly also his living space too, occupied by Morland and his man, Gibbs. Gibbs is listlessly cooking sausages over an open fire much to the interest of two expectant dogs. Preparatory studies of the same dogs – and maybe Gibbs too – appear on the wall above the fireplace. Crumpled boots and household items litter the scene. Morland has his easel set up by the only window and looks glumly out at us, while his near-complete painting shows the ideal of an English country cottage on a bright, sunny, Summer’s day. A recurrent theme, if the other paintings stacked behind him are anything to go by. We also see his painting materials on the stool beside him and the palette in his hand. Not many colours there, maybe seven? These are likely to be black and white, and a few others: evidence supporting Morland’s claim ‘that every possible effect might be produced with four or five colours’? Probably, but hard to tell for sure.

George Morland, The Artist in his studio and his man Gibbs, c. 1802, oil on canvas, 63.5 x 72 cm, Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery, NCM1904-55.

Apart from the blue sky on the unfinished painting, the blue of Gibbs’s blue stockings and coat and the red of the fire stand out. Those two colours again.

Blue Pigments have always been relatively hard to come by, a point made evident by the fact that Dawe is able to name numerous pigments for yellow and brown, but not for blue. Few natural minerals suitable as use for blue pigments exist, these are mainly lazurite (ultramarine), vivianite, azurite and its synthetic equivalent, blue verditer and the dye indigo. Smalt – a cobalt-doped glass – was widely available but know to be fugitive, and so unlikely to have been employed by the meticulous Morland. Prussian Blue became commercially available from the second decade of the 18th Century but the stable Cobalt Blue did not appear until 1775. The latter could have been used by Morland but like many other blue pigments, it would have been expensive.

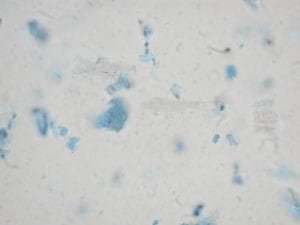

Could Morland’s blue be Prussian Blue? My gut feeling, from its slightly dull colour in the paintings, is that this is his pigment used for scarfs, caps and breeches. Cobalt blue and ultramarine are stronger, much brighter blues (though a preparation of cobalt blue, mixed with white could have been used for Morland’s skies). However we will have to wait for the opportunity to analyse the pigments of Morland’s paintings to be sure what was on his palette.

Prussian Blue on an organic substrate viewed under the microscope; plane-polarised light x 400.

Prussian Blue is a hydrated iron(III) hexacyanoferrate(II) complex. It is a synthetic pigment of extremely fine particle size and intense colour. It is relatively easily synthesised using readily available ingredients; dried blood (a source of iron), and alkali (i.e. potassium carbonate), iron sulphate hydrate, alum and hydrochloric acid. After heating the blood and alkali together, a red compound is formed which is then dissolved in water and filtered. The filtrate is then mixed with the alum and the iron salt and finally washed in hydrochloric acid, leaving a blue precipitate that is then ground to for the pigment (Samain et al., 2013). This process was first discovered in Berlin in 1704, earning it the early trade name of Berlin Blue.

References and further reading

Collins, W., 1806, Memoirs of that Celebrated, Original and Eccentric Genius the late George Morland, London: C. Stower.

Dawe, G., 1807, The Life of George Morland, London: Vernor & Co.

Grindle, N., ed., 2015, George Morland: Art, Traffic and Society in Late Eighteenth Century England., The Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery., 99 pp.

Grindle, N. M., 2015, ‘The gipsey-race my pity rarely move?’ Representing the Gypsy in George Morland’s Morning, or the Benevolent Sportsman., in: Dethloff, D., Murdoch, T. & Sloan, K. (Eds.), Burning Bright: Essays in Honour of David Bindman, 105-114. http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1470833/7/9781910634349_updated.pdf

Samain, L., Grandjean, F., Long, G. L., Martinetto, P., Bordet, P., Sanyova, J. & Strivay, D., 2013, Synthesis and fading of eighteenth-century Prussian blue pigments: a combined study by spectroscopic and diffractive techniques using laboratory and synchrotron radiation sources., Journal of Synchrotron Radiation., 20, 460-473.

‘The Artist in his Studio and His Man Gibbs’, George Morland, Art UK https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/the-artist-in-his-studio-and-his-man-gibbs-46834/search/actor:morland-george-17631804/page/6

George Morland: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Morland

Close

Close

The universally accepted method of removing the lamp black from the surface seems to be by scraping it off with a feather. In addition to Li Qiaoping’s descriptions, Jacobean gentleman Henry Peacham wrote in his treatise ‘

The universally accepted method of removing the lamp black from the surface seems to be by scraping it off with a feather. In addition to Li Qiaoping’s descriptions, Jacobean gentleman Henry Peacham wrote in his treatise ‘