What can peace education do on the eve of war?

By Blog Editor, on 22 February 2022

At the time of first writing, the headlines were saying invasion is “imminent” in Ukraine. Now Russian forces have occupied Donetsk and Luhasnk, with the threat of more intense violence still looming. That shouldn’t mean educators fall silent.

Young people do not exist in a bunker from reality – they hear the news and others talking about it. Many will know that something is up with Ukraine, Putin and Russia, even if no-one has talked to them about it. Silence about war is scary.

When violence escalated in Gaza in 2021, downloads of our education resources about Palestine & Israel increased dramatically, suggesting teachers were responding to the news in their classrooms.

Peace education can sometimes (and powerfully) focus only on the interpersonal level and leave war aside, perhaps fearing it is “too political”. This feeling may be still greater among teachers in England following the government’s new guidance on political impartiality. But a peace educator doesn’t campaign against war in the classroom. They help students build the combination of knowledge, empathy and critical reflection needed to be ethical, active citizens. So what would a peace education lesson about the prospect of war in Ukraine look like? What questions might we ask in the classroom?

Who is involved in the conflict?

Neville Chamberlain, UK Prime Minister at that time, said of the 1938 crisis in Czechoslovakia, it was a “quarrel in a far away country, between people of whom we know nothing”.

Today, despite the internet and increased global travel, many of us could say the same of Ukraine. How much do most British students – or indeed adults – know about Ukraine and Ukrainians? Or Russians for that matter, outside the stereotypes of James Bond movies. How do the Russian and Ukrainian students feel in the classroom as the news unfolds?

There are good human geography lessons to explore these diverse cultures. There are also compelling real stories of the people experiencing conflict, including journalists risking it all to tell the truth, Russian conscripts or Ukrainian conscientious objectors like Ruslan Kotsaba. What would we do in their shoes? Students could explore religious identity in both societies, including the 2019 split of the Eastern Orthodox Church and faith communities working for peace. Who are the Crimean Tartars? Ethnic Russians?

These are real people. Building empathy is one component of peace education. Chamberlain was in effect saying that the British people at the time, still living with the memory of World War I, wouldn’t care to go to war for so remote a people, but the effect can work the other way. A people ‘about whom we know nothing’, or not enough, is one whom we can unconsciously dehumanise, reducing them to statistics on the news.

Why could war break out?

To understand the present conflict, peace education can lead us to study history, and there’s lots to understand about Ukraine. As the Soviet Union came to an end, many Russians and Ukrainians were involved in nonviolent mass-movements including 300,000 Ukrainians who made a human chain for independence in 1990. There is more on the timeline to understand: Ukraine giving up its nuclear weapons and joining the Non-Proliferation Treaty; NATO’s expansion and Russians’ sense of betrayal’, Ukrainian movements from the orange revolution to the Maidan Revolutions. Perhaps it would be useful to look back further, to Britain’s Crimean War; to the USSR’s experience of World War 2 or ‘The Great Patriotic War’; to the Cold War and life in the USSR; to the Chernobyl disaster; or to the Holodmor, in which millions of Ukrainians starved under Stalin’s rule. What in this history contains the roots of the present conflict, and what needs to be addressed to make peace?

There are also contemporary Citizenship questions: what role do the arms trade or fossil fuels play? What is the UK’s role? What international law applies to war? What are the rights of the people involved: children, refugees, casualties, prisoners? From peace studies, learners can also gain insights into ideas such as structural violence, conflict escalation, cycles of violence.

During the onset of war, leaders’ rhetoric can be reductive, decrying any diplomacy as ‘appeasement’. We also know propaganda and “psy-ops” are an omnipresent part of modern warfare. If the first casualty in war is the truth, then education becomes doubly important so that citizens can see past the slogans, and exercise critical thinking. Perhaps that would make a good English Language or media studies lesson, but students need to be capable of evaluating the narratives purporting to explain why war is happening.

Is war bad?

Yes. War is bad, and it’s OK for teachers to say so.

Even those who say that war is sometimes necessary would generally concede that the experience is grim for everyone, unbearable for many. There’s no shortage of human experience teaching us about the suffering war causes.

For soldiers and their families, for civilians caught in the middle, for those forced to flee, for those left behind. This is not controversial, and our experience shows students can and want to grapple with the moral questions it raises.

But society is guilty of mixed messages on war. With media and culture rife with stories of redemptive violence and triumphs of arms, it is understandable if young people are drawn to the glamour and numb to the dangers. The regular presence of arms companies and military activity in education may also undermine a school’s duty to provide balanced views. Education needs to address the reality.

There are many perspectives to explore. RE teachers can draw on the different ideas on war and peace across different faith traditions. Literature can immerse us imaginatively in war; one of Britain’s most celebrated poems, The Charge of the Light Brigade, depicts heroic folly in war. History can explore the causes and effects of war, zooming in on the lived experience as well as the politics. The lives of Mary Seacole and Florence Nightingale might feel relevant too. Given four of the powers negotiating over Ukraine’s fate are nuclear armed states, the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons is also worth understanding, perhaps with resources from CND Peace Education or the Nuclear Education Trust.

Photo: Quakers in Britain

The facts of war must be handled sensitively in the classroom – students shouldn’t be traumatised. Teachers should also strive to be impartial about the political agendas surrounding war. But if democratic citizens are to engage meaningfully with a question like “should this war be fought?” it should be done with an understanding of the human consequences.

How do we make peace?

Peaceworkers time and again have to work against short-termism. The dilemma on the eve of war is too often reduced to “will you fight or do nothing?” What this ignores is the peacebuilding that can and should be done long before violence, addressing the needs of the parties involved and binding their interests. Think of the politicians desperately flying around on diplomatic missions, of the weapons flowing from East and West; could this energy and wealth have been more wisely spent in the preceding years?

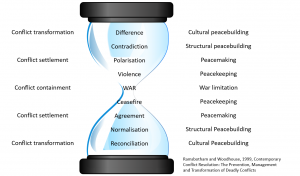

A helpful model of war from Peace Studies is the hour-glass. At its widest it provides space for conflict transformation, building peace and justice. As it narrows, options become limited to mere peacekeeping, or failing that, striving to contain the excesses of war.

The hour-glass also opens up gradually after we pass the narrow aperture of war, allowing for gradual normalisation and perhaps even reconciliation; planning for this post-war is important too. Lessons from the Rwanda genocide or the Coventry blitz show the power of peace even in the recollection of horror.

This model can help students understand many conflicts past and present, including Ukraine. It suggests the skills we could learn for each level: exchange and co-operation to build relationships when we see difference; mediation to get parties talking when they become polarized, which many school children practise every day; restorative justice when harm has taken place. There are myriad peacebuilding practices, and indeed careers for young-people so led. As Ivan Hutnik, a Quaker experienced in international conciliation and conflict transformation, puts it, ‘for real peace, the solutions need to be multi-layered and nuanced.’

Peace education is itself part of peacebuilding. Activities like the World Peace Game can help students role-play international challenges. The skills and processes required by the leaders responding to conflict in Ukraine can be learned, and students can practise them in the classroom, their everyday lives and careers.

The hour-glass is a reminder that education shouldn’t wait until that narrowing of options; the peace education ought to long before the eve of war.

Start somewhere

Peace education should start long before the eve of war and it’s no less relevant when violence breaks out.

If you had to run a 15 minute presentation the day war breaks out, what would you say? Perhaps I’d attempt a truncated version of this blog. First, war is bad and scary; talk to staff about your feelings. Second, the story behind the war is complicated, so ask questions and learn. Remember real people are involved, whether friend or enemy; we can hold all frightened people in our thoughts or prayers. And finally, there are ways to work for peace. That’s about all you could say.

But what else could you teach given time? Peace education isn’t extra-curricular. Throughout RE, English, History, Citizenship, PSHE, Social Studies, RE, Geography, not to mention Further Education or Higher Education, inspection frameworks, learning outcomes proliferate including conflict resolution, understanding the UK’s relations with the wider world, the Cold War, understanding different cultures, human rights, evaluating different narratives, reflecting on one’s own beliefs, religion peace and war. Across curricula a combination of knowledge, emotional engagement and ethical reflection can combine to help students own their own civic responsibility. Teachers and educators shouldn’t be afraid to go there.

War today is the failure of yesterday. The shadow of war continues to throw up some of the worst experiences and dilemmas humans can face. Questions that seem unanswerable, stakes incalculable. That is why they can’t be avoided – teachers and educators have to start somewhere. If we are to find better answers than war, we need peace education.

Author Biography:

Ellis Brooks is the Peace Education coordinator at Quakers in Britain. His passion for peace and justice comes from volunteering in Palestine, Afghanistan and in his home country of Britain, campaigning on issues including the arms trade, nuclear weapons and violent immigration systems. Having worked as a teacher, Ellis has experience of the both the pain and the peacebuilding that exist in schools. Find out more at www.quaker.org.uk/peace-education

Close

Close