Nineveh Gates: Challenges, Sustainability and Strengthening Community Relations in Mosul

By Zainab, on 18 June 2025

We talk to Mustafa Yahya Faraj, an archaeologist with the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage. Mustafa held a Nahrein – BISI Visiting Scholarship at UCL. His project is titled Nineveh Gates: Challenges, Sustainability and Strengthening Community Relations in Mosul and is under the supervision of Professor Mark Altaweel.

Mustafa with Prof Eleanor Robson at UCL

Tell us a little about yourself.

I’m an archaeologist from Mosul, Iraq. I hold both a Bachelor’s and a Master’s degree in Ancient Archaeology from the University of Mosul, and I have been working with the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage of Iraq (SBAH) since 2013. I have worked at some of Iraq’s most significant heritage sites, including Nineveh, Nimrud, and the Mosul Museum, where I’ve been actively involved in excavation, restoration, and emergency rescue projects. These experiences have also allowed me to collaborate with esteemed institutions such as the University of Mosul, the Smithsonian Institution, and the University of Heidelberg.

From 2023 to 2025, I was part of—and helped lead—the restoration project of the Mar Toma Syriac Orthodox Church in the old city of Mosul. This initiative, supported by the ALIPH Foundation and L’Œuvre d’Orient, aimed to revive one of the city’s most iconic landmarks. I’m also passionate about documenting historical buildings and sites, especially in Mosul before and after the ISIS occupation. My work includes extensive photographic and written documentation to help preserve cultural memory and identity.

I have completed several international training programs, including a rescue archaeology course at the Iraqi Institute for the Conservation of Antiquities and Heritage (IICAH) in Erbil, and courses on archaeological entrepreneurship offered by Koç University and the University of Bologna. In 2025, I was honored to serve as a Visiting Scholar at the Institute of Archaeology – UCL, where I conducted research on the social, economic, and cultural impact of the Gates of Nineveh on the local community.

I am a member of ICOMOS and ISCARSAH, and throughout my career, I have received over fifteen certificates and letters of appreciation from both Iraqi and international institutions in recognition of my contributions to heritage preservation.

Tell us more about your project.

My research project focuses on the Gates of Nineveh from three key aspects. First, it involves assessing their current condition, documenting violations, and reviewing previous excavation rescue and restoration efforts after 2017. Second, it explores sustainable approaches to the conservation and management of the gates. Third, it examines the relationship between the gates and the local community, how people interact with these structures and perceive them as symbols of heritage and identity.

How was your Visiting Scholarship experience in the UK?

My Visiting Scholarship experience in the UK was truly transformative, both academically and personally. I had the honor of joining the Institute of Archaeology at University College London (UCL) as a Visiting Scholar, where I focused on researching the Gates of Nineveh. This opportunity allowed me to engage with outstanding researchers, and explore the British Museum and UCL’s extensive library collections.

Living in the UK gave me the chance to learn about the country’s rich heritage and preservation practices. I visited several historic sites including Avebury, King Richard III Visitor Centre, and the city of Bath. These visits offered hands-on insight into how archaeological sites are presented, protected, and integrated into public life. I was especially impressed by the museum interpretation techniques, the integration of digital media in storytelling, and the urban planning efforts to preserve architectural identity in historic cities like Bath.

Equally important were the cultural experiences exploring London’s communities, visiting monuments and landmarks, and building friendships with people from around the world. These moments broadened my perspective and strengthened my belief in the importance of international collaboration in cultural heritage protection.

The knowledge, skills, and inspiration I gained during this scholarship are already influencing my work in Iraq, especially in documentation and site management. I am grateful to the British Institute for the Study of Iraq (BISI) and Nahrain Network for making this journey possible, and I look forward to building on this experience in future heritage projects.

What were the main benefits of your scholarship?

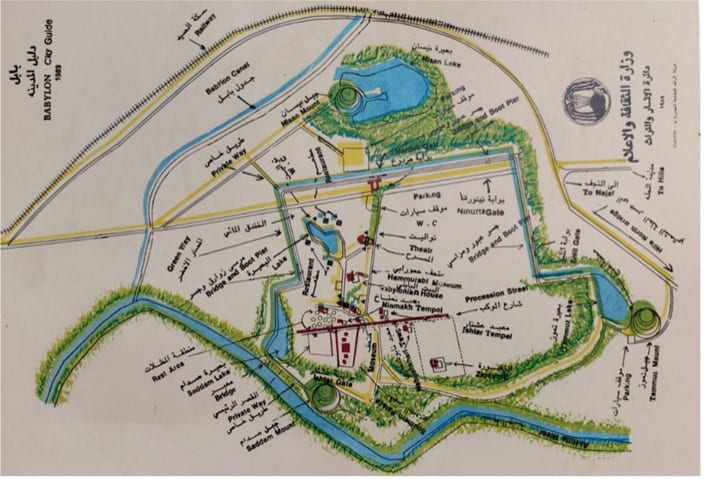

I was given a remarkable opportunity to start conduct research on the Gates of Nineveh at the Institute of Archaeology – UCL, focusing on four key aspects. First, the study the current condition of the gates and the violations they have been subjected. Second, it explored methods of archaeological site management and sustainability, with the aim of adopted these practices to the Gates of Nineveh. Third, it investigated the relationship between the gates and the local community, considering them as symbols of cultural identity, tourist attractions, and potential agents of community healing in Mosul’s post-conflict context. Finally, the research involved the creation of a new multi-layered map of the Gates of Nineveh, based on aerial and satellite imagery. This map includes three layers: the first from Royal Air Force (RAF) aerial photographs taken in the 1920s, the second from CORONA satellite images dating to the 1960s, and the third from recent satellite imagery, allowing for a comparative analysis of the gates condition over the past 100 years. Without this generous scholarship, it would not have been possible to carry out the research in such depth and from these important perspectives.

What was the main highlight of your scholarship?

The main benefits of my scholarship included access to academic resources at UCL and the other institutions, as well as the opportunity to engage with leading experts in archaeology and heritage preservation. I visited archaeological sites and museums across the UK to learn new methods of site management and sustainability, with the aim of adopted these practices to the Gates of Nineveh. The experience also allowed me to expand my professional network and gain valuable insights into the protection and promotion of cultural heritage.

What were the main things you learnt from your Host Institution?

From my host institution and supervisor, I learned advanced methods of interpretation and heritage management. I gained a deeper understanding of conservation and promotion strategies for archaeological sites, enhanced my academic research skills, and learned how UK institutions collaborate with local and international partners on heritage projects.

How has the scholarship helped you in your work in Iraq?

The scholarship has significantly strengthened my ability to contribute to the preservation of Iraq’s heritage. It equipped me with sustainable methods for managing archaeological sites, which I can apply in Mosul. Additionally, it broadened my perspective on how heritage can serve as a powerful tool for reconciliation, education, and economic development.

What will you do to continue your research in Iraq?

I will continue my research by collecting field data from the Nineveh Gates, analysing satellite imagery, and interviewing local residents about the cultural significance of the gates. I plan to publish my results and contribute to national and international discussions on the preservation and future of Nineveh’s heritage.

Close

Close