Recordkeeping with Love

By Victoria Hoyle, on 21 January 2019

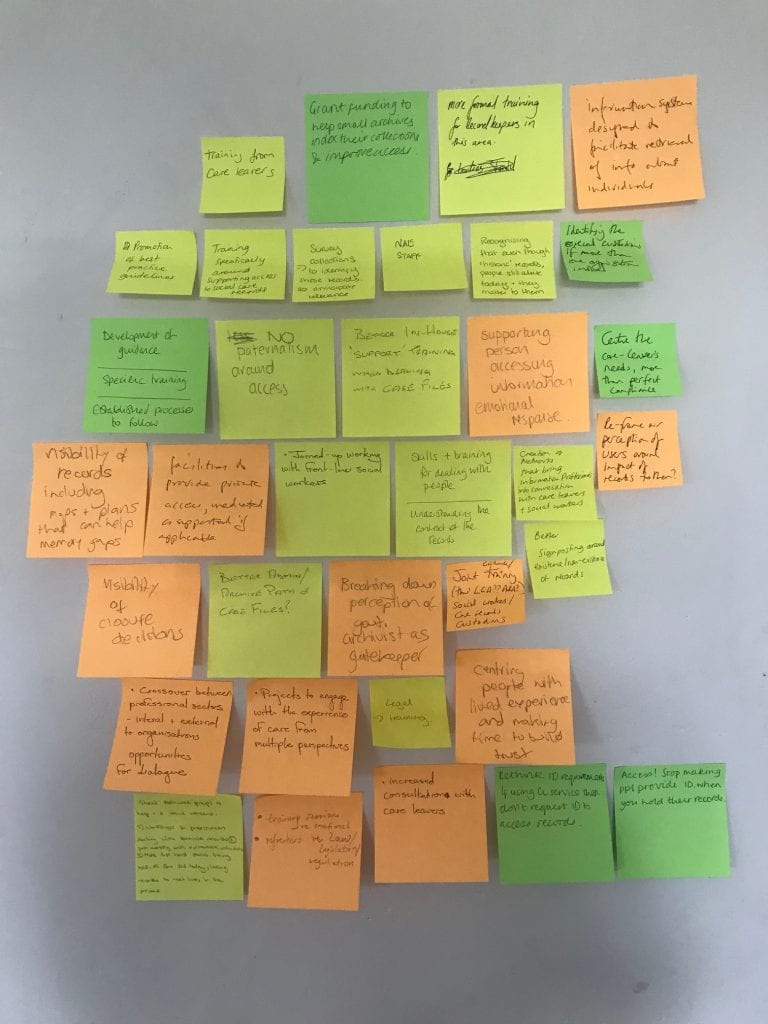

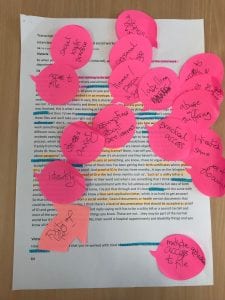

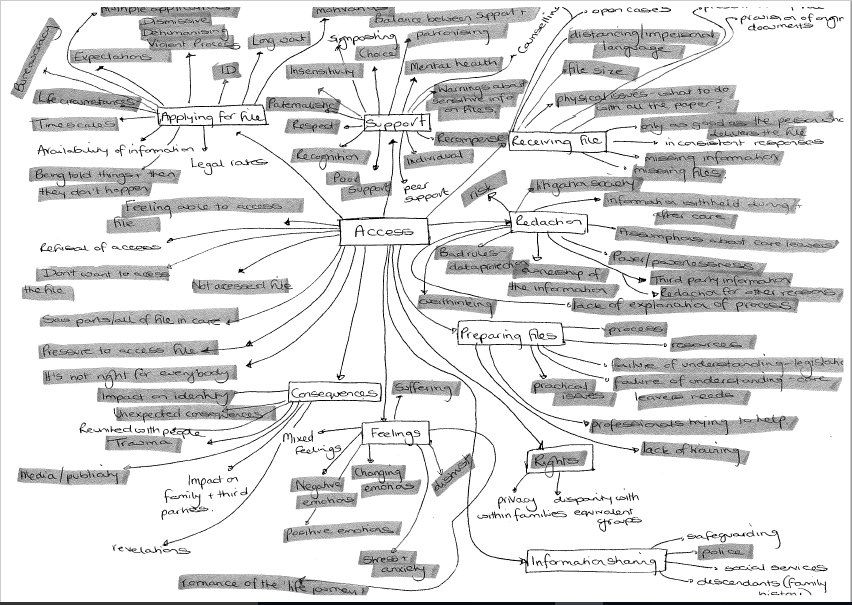

Over the last year I’ve spoken to a lot of people about accessing their social care records, and about their experiences in care and as care experienced adults. I’m currently working back through the interview transcripts and focus group recordings, doing primary data analysis based on the coding framework we co-designed last year. I’ve been struck by how often the conversations turned to solutions. Not just to recordkeeping problems but to the bigger issues of the lack of identity, belonging and mental wellbeing that so often motivate people to go looking for their records in the first place. Revisiting these discussions has been powerful and illuminating, challenging me to think about what we, as a research team, can do to improve people’s lives.

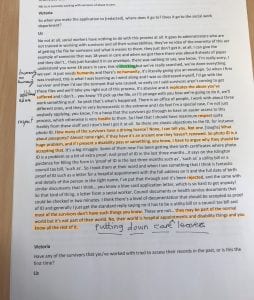

The most common answer I’ve heard is ‘more love’. People have often talked about how the absence of love, and of simple expressions of care like hugs and cuddles, left lifelong wounds for them. Accessing records is often part of the process of healing, through understanding what happened to them and why. But unfortunately records and the access process can reinforce rather than help the hurt. This is because records are so often the product of loveless or careless ‘care’: they are the tangible evidence of the way a child or young person has been turned into a task, a job and a statistic. The process for accessing records can be similarly dehumanising. Long waiting times, lost files, heavy redactions, and poor (or non-existent) aftercare seem to underline the message that you’re not important. Several people have shared common experiences of being told ‘oh we can’t find you, according to the system you don’t exist’. Others have been advised, at the point of accessing their records, that ‘there’s nothing very interesting in there’ or ‘I’ve seen much worse.’ This way of speaking and thinking about the records is felt as a commentary on the person themselves, even if that’s not what is consciously intended. To hear that you don’t exist, or that the most important events of your childhood are uninteresting is very hurtful. Generally, it shows a lack of empathy in social care recordkeeping that begins at the point of creation and carries on right through to access in adulthood.

I have to admit that I’ve often wondered what MIRRA can do to make an appreciable positive difference. We think part of the answer is compassionate guidance and better training, and strong evidence to support fairer legislation, but how do we make the case? Especially at a time of diminishing financial resources, huge social work case-loads and the highest number of children in care since the 1970s. In thinking about this question I’ve been coming back again and again to love.

This morning I watched a TEDTalk by Scottish care leaver and residential care manager Laura Beveridge, about the need for a revolution of love and equality for children in care. It’s a few years old now, but if you haven’t seen it, I urge you to watch it: youtu.be/E-wp7HN9Zvs . In it she talks about what it’s like to live in a world where ‘you don’t call your parent mum or dad, you call them staff’, where you have to sign an official form to get your pocket money and where what you can do and where you can go depends on a risk assessment. She talks about leaving care with a box of administrative papers rather than a memory box of photographs and mementos.

This further convinced me of the fundamental importance of love in recordkeeping. Social care records have a statutory and official role in Children’s Services, but surely they also have a critical function in capturing and demonstrating the love that we want all children and young people to feel. If a commitment to social records created with and for love ran right through the recording function and on into the access process then ‘files’ could be better in lots of ways. Better at supporting and informing child-centred social work practice; better at capturing the key moments and memories of childhood; and better at helping to answer the lifelong needs of care-experienced adults. Drawing on the work of psychologist Gerard Egan (2000) Michelle Caswell and Marika Cifor (2016) have challenged recordkeepers to bring ‘radical empathy’ to their work. They define radical empathy as “a willingness to be affected, to be shaped by another’s experience, without blurring the lines between the self and the other.” By rethinking the value of social care records as evidence of love, and coming to a better understanding of why records matter to everyone involved in making and preserving them, we might come to see them as tools for caring rather than for surveillance and judgement. Increasingly I feel that bringing more love into recordkeeping has to be a key aim of our research outputs.

Close

Close

This post was written by Gina Larrisey, a care experienced co-researcher working on the MIRRA project.

This post was written by Gina Larrisey, a care experienced co-researcher working on the MIRRA project. At the end of May my colleague Elizabeth Shepherd and I visited the London offices of the

At the end of May my colleague Elizabeth Shepherd and I visited the London offices of the The lack of records or their poor management also ‘caused distress to the former child migrants who were affected’ throughout their lives.

The lack of records or their poor management also ‘caused distress to the former child migrants who were affected’ throughout their lives. formation recorded about children in care, a routine feature of daily life in the care system, is profoundly important and can have an impact not just on the subject of the records but on those close to them for generations. What is written, how it is written and the language used is so very important, but how rarely this impact seems to have been a consideration over the years.

formation recorded about children in care, a routine feature of daily life in the care system, is profoundly important and can have an impact not just on the subject of the records but on those close to them for generations. What is written, how it is written and the language used is so very important, but how rarely this impact seems to have been a consideration over the years.