Tailoring cessation support for disadvantaged smokers – is it working?

By e.schaessens, on 5 December 2019

Author: Loren Kock, PhD student, Tobacco and Alcohol Research Group

Smoking cigarettes remains a leading cause of preventable death and disease in many high-income countries. Most of these harms fall disproportionately upon socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals who generally have greater difficulty in quitting and remaining abstinent. In increasingly resource constrained health systems, what role does behavioural support that is tailored to an individual’s socioeconomic position (SEP) play in helping smokers quit and stay quit?

Smoking cigarettes remains a leading cause of preventable death and disease in many high-income countries. Most of these harms fall disproportionately upon socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals who generally have greater difficulty in quitting and remaining abstinent. In increasingly resource constrained health systems, what role does behavioural support that is tailored to an individual’s socioeconomic position (SEP) play in helping smokers quit and stay quit?

Reducing health inequalities, which includes access and provision of health-care services, has been included as one of the UN’s sustainable development goals (SDG 10). Given that smoking is estimated to kill almost 8 million people a year and largely falls along a socioeconomic gradient, acting to prevent uptake of smoking and to help existing smokers quit is an essential part of this goal. Alongside other interventions and policies, the WHO’s ‘MPOWER’ package of measures to reduce the prevalence of smoking worldwide, provision of behavioural support to individuals trying to quit smoking is widely thought to be an effective approach. An advantage of these interventions is that health providers can be flexible in their delivery; support can be delivered in-person or over the phone, via digital media or through the use of financial incentives.

To tailor or not to tailor?

Even with the best support, most people relapse to smoking within the first month of quitting. Interventions that are tailored to smokers from disadvantaged groups stem from the knowledge that these individuals have greater difficulty in quitting and remaining abstinent than do those from more affluent groups. This is largely due to issues such as financial stress, absence of social support, addiction, lower confidence, stress, scarce life opportunities and less interest in the harms related to smoking. Because they don’t specifically address these barriers, it is generally thought non-tailored interventions are generally less effective among disadvantaged groups and may therefore be exacerbating existing inequalities. Compared with interventions that have no specific demographic target (non-tailored), interventions that are tailored to address these socioeconomic barriers (SEP-tailored) could, at least in theory, be more successful.

Our study published in the Lancet Public Health sought to tease out how much more effective, if at all, SEP-tailoring was for helping socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers quit.

Is SEP-tailoring more effective?

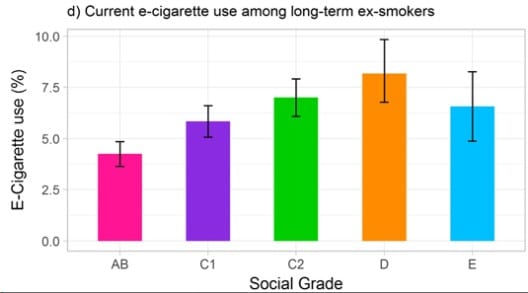

Our analysis of long-term (6 month) smoking cessation among disadvantaged participants from 42 randomised controlled trials revealed that individual-level behavioural support, regardless of whether or not it is tailored, can assist disadvantaged smokers with quitting. As aforementioned, tailored approaches specifically are expected to have an important role in reducing health inequalities by addressing some of the needs specific to disadvantaged smokers. However, further analysis revealed that when compared with not tailoring, SEP-tailoring was no more effective.

Quitting is hard

These results highlight the challenges that disadvantaged smokers face when making a quit attempt. It’s likely that behavioural support is effective in the short term, but the benefits wear off or disappear entirely when weighed against the circumstances and stresses that a recently quit ex-smoker faces every day. Dealing with the cravings and withdrawals associated with abruptly coming off the highly dependence-inducing nicotine from cigarettes, while also having to face unstable employment, low income, poorer housing conditions and general lack of support makes it much more likely that a disadvantaged ex-smoker will find themselves returning to smoking. It may be that even when tailored behavioural support attempts to adjust for SEP, it isn’t quite enough when weighed against these life circumstances. However, although no more effective than non-tailored approaches, tailoring is still an effective method; our analysis estimated that all types of behavioural support can improve quit rates by over 50%.

Doing more, and better

These findings don’t imply that tailored approaches should be abandoned. Instead, they should be a call to action for improved, multifaceted approaches at the individual, community, and population level that recognise the wider context of socioeconomically disadvantaged smokers. Sometimes complex problems require complex solutions!

Read the paper: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(19)30220-8/fulltext

Close

Close