What’s law got to do with it?: Reflecting on my time in the Q-DaPS team as an In2research student

By Eleanor Mason, on 17 July 2025

Student Shania Essah Aurelio shares her experience with the Q-DaPS (Qualitative Data Preservation and Sharing) team at the UCL Institute of Epidemiology and Health Care through In2research. In2research is a one-year programme developed by In2scienceUK and UCL, designed to enhance access to postgraduate research degrees and career opportunities for people from low socioeconomic backgrounds and under-represented groups.

Why I chose this placement

The Q-DaPS study is a multidisciplinary research study led by academics and Public & Patient Involvement (PPI) experts. It is funded by the NIHR School for Primary Care Research (FR4 – Project No. 596).

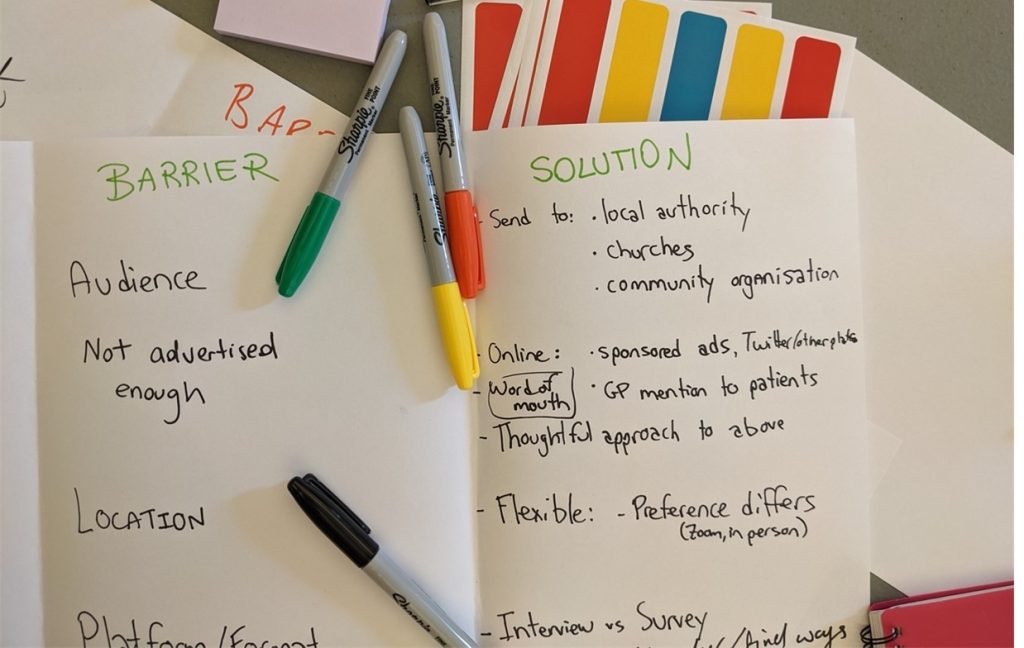

The study’s primary objective is to create a centralised repository for qualitative health and social care data that is secure and trustworthy. To inform the repository’s design and infrastructure, this study involved interviews with data professionals and qualitative researchers as well as focus group discussions with PPI collaborators who have previous experience of participating in primary care research.

Despite not coming from a medical sociology background, I applied to the Q-DaPS project for three main reasons:

- I was curious to look at health data from a different perspective. For context, I was completing my Masters degree in Law at the time, where I had been researching data protection laws and how they’re applied to personal data processing activities in the public sector.

- I wanted to learn about how qualitative data are used and managed in health and social care research, as well as the issues that may arise from this.

- It was clear that collaboration was at the project’s core from the very beginning and I wished to be part of a co-created project between academics and PPI contributors.

Looking back, I can confidently say that my time with the Q-DaPS team has definitely exceeded those expectations.

Working with the research team

Throughout my placement, I met and worked with various members of the Q-DaPS team: Professor Fiona Stevenson (who was my placement host), Professor Geraldine Leydon, Dr Barbara Caddick, Dr Karen Lloyd, and patient and public involvement (PPI) experts Lynn Laidlaw and Ali Percy.

PPI increasingly plays a central part of health and social care research. Safe to say, I had never worked with PPI contributors before. That, mixed with the readings I’ve done in a discipline I’d never come across before, would explain why I came to the first full team meeting with a page full of questions: from “how does triangulation work?” to “how do PPI contributors get onboarded on research projects like this?”. I knew that delving into a whole new discipline was going to be a challenge, so I’m thankful to the Q-DaPS team for actively involving me in their discussions and patiently explaining concepts and terminology that I couldn’t get my head around.

Another in2research student, Kim McBride, also joined the Q-DaPS team later that summer. Even though we didn’t start our placements at the same time, we got to work together on days when our schedules overlapped. In retrospect, it was probably for the best—every time we were in the same room together we always ended up chatting about our studies and research interests. I really enjoyed working with Kim; like the rest of the Q-DaPS team, her contributions were informed by the work she’s done in her discipline (which is Social Psychology) and getting to see the same dataset (i.e., focus group transcripts) from her perspective was incredibly valuable.

Working on my project

The Q-DaPS project involved a qualitative multistakeholder study, which essentially means that there’s a lot of reading involved—especially in the earlier weeks of my placement. Before homing in on the focus group transcripts, I went through interview transcripts from the multistakeholder study, where I gained insights from various experts in the field (i.e., PPI contributors in health and social care research, researchers, and data protection lawyers).

Having gone through the focus group and interview transcripts, I ended up researching the intersections between UK data protection law and health data-related research ethics. I mainly focused on the UK GDPR as well as the Taipei and Helsinki Declarations. Through this placement, I got to explore the connections between them which I thoroughly enjoyed.

What made the research process enriching was the feedback phase; this is where the varied expertise of the Q-DaPS team shined. Looking back on the dialogue I developed with the Q-DaPS researchers through the ribbons of comments on my research outline, I have learned so much from their experiences—from how data protection laws are applied in academic settings to how data ethics are approached by ethics committees across institutions.

Even though I was based in the Department of Primary Care and Population Health, I got to meet researchers from other departments. From them, I learned more about topics like social prescribing, safety standards for baby food, and even health economics—things I’d never looked into before. Being able to hear about their research and share experiences and anecdotes with them really encouraged me to keep going with my project.

The chances of being onboarded onto a medical sociology research project with a CV filled with legal research experience are very slim, and I am very grateful to the in2research team for having afforded me this opportunity by matching me to the Q-DaPS placement. My gratitude is extended to the Q-DaPS team, who have warmly welcomed me into their side of the research world and enthusiastically encouraged my curiosity.

Close

Close