The prejudice of shallowness

By Razvan Nicolescu, on 4 April 2014

Isabella has 28 years old and is engaged (fidanzata) for eight years with a man from a nearby town. In this part of Italy these long engagements are quite common. Actually, Isabella has the most recent engagement in her close circle of friends, who are all engaged for 10 or 12 years. The marriage is thought of as something that should be built on solid grounds, typically a stable workplace and a house. Customarily, the man first builds a house, furnishes it at least partially and then the couple organize the wedding ceremony. In the context of difficult economic circumstances and high social uncertainty these conditions for even thinking of a marriage are quite difficult to be attained.

Isabella is happy that she works full-time as a shop assistant and has time to also study for her undergraduate degree. She is proud she will most probably graduate this year. She started to study Letters at the University of Salento eight years ago. All along this time, her fidanzato supported her determination to complete her studies even against the will of her family. However, during this time the couple was not able to save money for the marriage. He always worked on a temporary basis as a builder and her current job as shop assistant is the first stable job any of them ever had. They estimate that the wedding ceremony alone would cost them at least 10,000 EURO. They come from modest families who could not raise even a small part of this sum. The plan is that Isabella should graduate first and then they could start saving money for the wedding. This means the two could get married in at least two or three years.

Until then, and as most of the fidanzati in the town, the two live separately each with their own families. They also work in the same towns where they live. As the two towns are situated about ten miles away one from the other, they currently do not manage to see each other too often during work days – which here are Monday to Saturday. The two compensate this by spendings the weekends together, living alternatively at one of their parents’ house This arrangement also allows them spending more time with their friends.

Isabella’s closest friends are six female ex-colleagues from her secondary school in Grano who happen to be all engaged with six men from the town of her fidanzato. He is actually a cousin of her best colleague from her secondary school class. She remembers that this was her favourite group of friends since she was a teenager. She always enjoyed the fact that they had the same tastes and very similar passions on a gendered basis. I will not detail this here, but is important to mention that the group itself and this shared intimacy within its strict confines is what makes Isabella feel safe and comfortable.

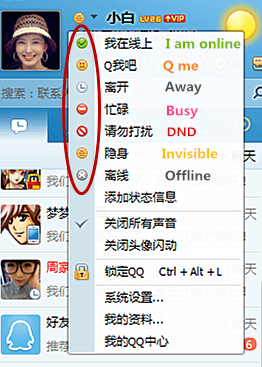

Whatsapp is important in keeping this sense of intimacy. The group of friends use three main Whatsapp groups: ‘the group of girls,’ ‘the group of boys’ and the group for all of them which is also the least used. Girls use their group most intensively by far: they may start the day with a simple buona giornata (‘good morning’), a question, or a video clip. At least two hours until work starts, roughly at 10:00, there is an energetic exchange of messages and updates inside this group. The boys use their group rather irregularly, with typical peaks such as the ones around the dates when Juventus Torino is playing. What is important for this discussion is that Isabella senses that her fidanzamento depends on the unity of the group of her female friends and this unity currently knows a substantive support because of Whatsapp. Isabella sees that many women of her age become less attached to their peers when they start to work or move closer to their marriage, and therefore, she is extremely happy that Whatsapp allows her reinforce what she senses she needs most.

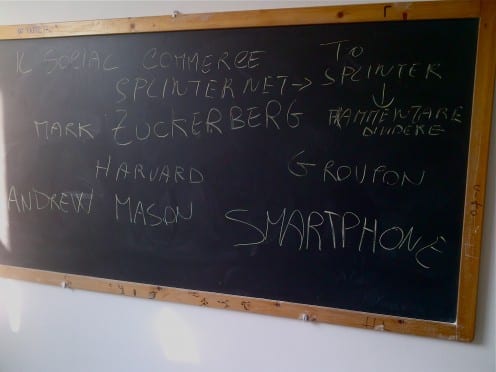

At the same time, these people who could have a noisy aperitivo in large groups of twelve-fifteen people in late summer evenings could easily be accused of a certain shallowness. A typical criticism is that they ‘stay too much on’ their Smartphones when they are supposed to be together. This blog post goes against these prejudices and social condemnations by suggesting a few reasons why these could simply not be true. Beautiful well-dressed women and jovial men could cheerfully manipulate their Smartphones not because they are more distant one from another but because actually they want to be much closer.

Close

Close