Chinese low-end smartphone market: the era of ‘shanzhai’ has passed, budget smartphones dominate

By Xin Yuan Wang, on 6 May 2015

Budget smartphones on sale at a local mobile phone shop in a small factory town ( Southeastern China).

My individual project began with one general inquiry about the social media use among Chinese rural migrants in a small factory town in southeast China. Eventually this led to the acknowledgement of the significance of the budget smartphone, as the ‘mega digital terminal’ in those low-income people’s daily life.

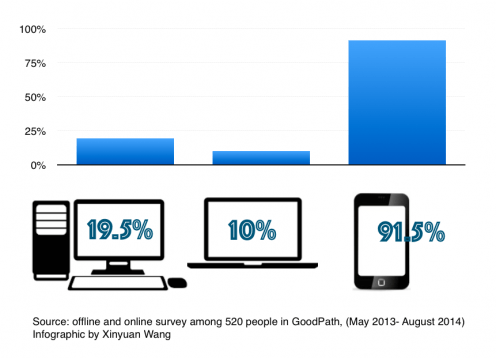

The number of Chinese mobile Internet users has reached 527 million, making mobile phones the most common device for accessing the Internet in China. Such figures become even more impressive in my fieldsite where most people cannot afford a PC or other digital devices. Smartphones have become their first private access to the internet. Budget smartphones dominate the market, the average price for a smartphone is around 500 RMB ($80). The average monthly cost is around 100 RMB ($16). According to a survey conducted among 520 persons in the fieldsite, 91.5% of people, the majority of them are rural migrants, use smartphones to get access to the internet, and only 10% use laptops, and 19.5 % desktop computers as internet devices (see chart below).

According to the local mobile phone dealers, shanzhai mobile phone, the knock-off low-priced mobile phone, used to be very popular. Usually, the price of a Shanzhai is 1/5 to 1/10 of the ‘real brand’. However, since the end of year 2012, the shanzhai mobile phones have started to shift in terms of sales strategy. Previously they just copied famous brand names. Now some shanzhai mobile phone manufacturers have set up their own brand-name phones and newly designed budget smartphone brands like ‘XiaoMi’ (Mi-One). Also, major Chinese telecom companies have started to invest in qianyuan ji market (Smartphones with a price lower than 150 dollars) and launched a few heyue ji (contract mobile phone) packages together with Chinese local mobile phone manufacturers such as HuaWei. With 10 to 15 dollars monthly fixed baodi xiaofei (guaranteed consumption), one can get a smartphone for around 50 dollars or even for ‘free’. These inexpensive smartphones quickly captured the low-end smartphone market by offering similar price points along with better quality devices, and after-sale service than their shanzhai competitors. As a result the shanzhai era of Chinese low-end mobile phone market has already passed.

It was the young rural migrant who drove the local budget smartphone market. The majority (80%) of young rural migrants (age 17- 35) already own a smartphone, and 70% of smartphones that people currently use are their first, and 1/3 of people reported that they wanted to have a smartphone with ‘good brand’ (hao paizi) in two years time when they have saved up enough money. A ‘good brand’ (such as iPhone and Samsung) is regarded as a symbol of social status.

For most rural migrants who still cannot afford a ‘good brand’ smartphone, budget models may not bring them an elevated social status, but will definitely make a lot of changes in their daily lives. The smartphones actually created a ‘media convergence’. Their smartphone is not supplemented by a landline, and their are used as their first camera, first music player, the first video player, and the first game machine. Researchers in other developing field sites, such as India, Chile and Brazil all find the similar trend of budget smartphone usage among low-income population. Such phenomena mean the study of smartphones is more than just looking at the mobile phone as a single communicative channel, but about analysing the whole-package media solution and the holistic media environment which we call ‘polymedia‘ in the age of smartphone.

Close

Close