On the Brazilian crisis, Pentecostalism and thinking out of the bubble

By Juliano Andrade Spyer, on 26 April 2016

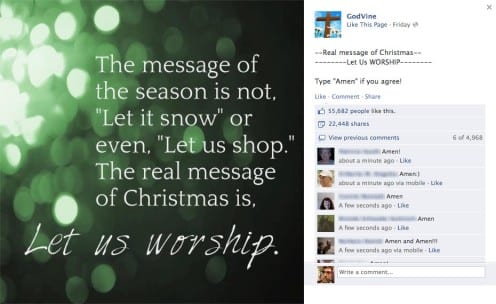

Pentecostal service in the Brazilian field site. Photo by: Juliano Spyer

Brazil is in the midst of a heated national debate between people in favour of, and those contrary to, the impeachment of the president. Because of social media, the sharing of different political views is also causing divisions in the private domain among friends and among family members. But a glimpse at the Facebook timelines of low-wage Brazilians demonstrates how millions of Brazilians are actually not interested in this debate.

A text written by a dweller of Morro do Viradouro, a shantytown in Rio, explains why the low-income population is not concerned with the national political debate. The idea that the impeachment is a coup d’état does not convince favelados, he argues, as for them the institutional killing and torture of the military regime (1964-85) never ended. Another low-income group is also not using social media to learn about or share points of view about politics: the evangelical Christians.

The lack of interest displayed by affluent Brazilians for this group appears in a piece by The Economist that circulated broadly in Brazil. It presents how Brazilian congressmen and women justified their vote during the session about the impeachment, highlighting the stereotypical carnivalesque aspect of the event and missing the opportunity to note that many of the reasons for the vote for impeachment referred to family, religion and God. These are relevant topics to 25% of Brazilians who are evangelical Christians.

Market analysts use the expression to ‘think out of the box’ to refer to creativity. An ethnographic version of this expression could be to ‘think out of the bubble’; in the case of Brazil, the bubble is social class.

Among the educated middle-class, evangelical Christians are seen, at best, as religious fanatics, but more commonly as backward, ignorant, and even evil conservatives. Having lived for 15 months conducting anthropological research in a working class settlement in the state of Bahia, I had a more nuanced experience of this group.

Firstly, I saw that although they are morally conservative, evangelical Christians are not stupid or intrinsically dishonest as the stereotypes dictate. Their broad ambition to achieve financial success is, in most cases, a desire to be part of the same world of consumption that the affluent have access to. But beyond that, their contributions to society are almost completely unacknowledged.

Their religious organisations are often more present and active in the lives of socially vulnerable people than the government. Let us not talk of spiritual support to avoid discussing faith and religion. Pentecostal organisations actively promote literacy and also intermediate the contact of church members with specialised services including doctors and lawyers. And by ‘recycling the souls’ of drug addicts and criminals, they provide an unrecognised but priceless service to society – much better than the police could ever hope to offer.

I am not denying that they possess conservative views regarding themes such as abortion or gay rights, but I am offering a more ethnographically-grounded view. There are 100 million Brazilians (half of the country’s population) that belong to the deemed ‘new middle class’ (actually, an emerging working class), and Pentecostalism has an undervalued contribution to this process of socioeconomic change.

The difficulty that more affluent Brazilians have in relating to evangelical Christians is maybe because this group, though generally struggling financially, do not identify themselves with the clichéd and victimised image of poor people. They are improving in spite of social stigmas and the legacy tied to the historical inequalities of Brazil. They are often depicted as fanatics in the media and yet their embracing of education is not mentioned. They are seen as morally conservative but nobody points to the reduction of domestic violence and of alcoholism in evangelical Christian families.

In this regard, affluent Brazilians need to step outside of the class bubble and look at evangelicals with more generosity and interest, and with less prejudice. Then they might be better equipped to understand why evangelical Christians are missing from the debate about politics on social media.

Close

Close