In 1966, Peter Beal, a graduate of the University of Leeds, started work on the Index of English Literary Manuscripts, 1450-1700 (IELM). The first volume of what was originally meant to be a one-year project appeared in 1980. Its two parts covered the years 1450 to 1625 and were followed, in 1987 and 1993, by a further volume in two parts taking the coverage up to 1700. For the first time, English Renaissance scholars had a full catalogue of the manuscripts – autograph and scribal – of the major authors of the period. The Index included writings in verse, prose, dramatic, and miscellaneous works, including letters, documents, books owned, presented, and annotated by the authors, and related items. In 23,000 entries, Peter Beal covered the works of 128 authors – of these two were women: his choice was determined by a decision to base the whole project (further volumes covered the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) around authors with entries in The Concise Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature (1974). Each author’s entry begins with a valuable introduction giving an overview of the surviving material.

The project initiated a series of investigations into what has come to be known as ‘scribal publication’, and this phenomenon in itself has contributed an important element to the study of the history of the book in Britain. Following the Catalogue’s publication, Peter Beal continued to collect material relating to the authors whose manuscripts he had already described, and by the early years of the new century he was ready to find a way of updating the Index. A proposal in 2004 to the Arts and Humanities Research Board (later Council) for a five-year project to create an enhanced digital version of the Index was successful, and the following year work began on The Catalogue of English Literary Manuscripts, 1450-1700 (CELM). Since then, Peter Beal has continued his researches, assisted by John Lavagnino of King’s College London’s Centre for Computing in the Humanities, who has acted as the project’s technical advisor, while I have acted as its general overseer, along with a distinguished international advisory panel .

CELM will cover the work of around 200 authors (60 of them women) in some 40,000 entries. The author entries range in length from having no items (Emilia Lanier and Isabella Whitney) to having only one (Thomas Deloney and Sir Thomas Elyot), to having around 4,500 (John Donne). A conference relating to the project was held at King’s in the summer of 2009, when the database was shown to a number of scholars, and the Catalogue will be launched online as an open-access resource at a larger event in the summer of 2011.

Work on CELM began with keyboarding all the entries in IELM, turning the contents of the books into a database. In many ways, CELM is instantly recognisable as a digital version of IELM. However, whereas IELM was solely based around authors, CELM has a repository view as well as an author view – both are available in longer and shorter forms. The repository view allows the user to see what is available in some 500 locations from Aberdeen University Library to the Zentralbibliothek, Zürich, Switzerland, by way of numerous Private Owners and Untraced items. Even though the repository view only contains descriptions of items by CELM’s authors, it is a major step towards producing what is in effect a short-title catalogue of English manuscripts of the period.

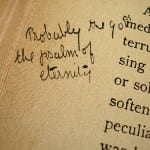

Much thought has been given to the question of tagging material and to the possibilities of full-text searching. For example, it will be easy to find some specific literary genres, such as verse letters or epigrams by text searching, but other ‘hidden’ categories, such as women, scribes, compilers, owners, collectors, composers, dealers, bindings and binders will remain elusive unless tagged. The project has enormous scope for further development. It might, for example, supply links to library home pages and their catalogues and to related digital projects such as ODNB, Perdita, and the Electronic Enlightenment. Most importantly of all, there are several areas where CELM offers a valuable starting point for further research: for example, into paper and bindings, auction and booksellers’ catalogues, the history of scribal publication, literary genres, authorship, and collecting. One obvious development would be to link entries to images of the material that is being described, while in time it is hoped that full descriptions of each manuscript referred to can be created. There is scope for more work on as yet unvisited repositories, as well as for including more authors and literary types, especially anonymous works. Some thought has already been given to how to maintain the website and how to signal the addition of new material to users.

What began as a simple one-year survey of what was thought to be quite a limited field has grown, through Peter Beal’s extraordinary labours, into a vast digital project that will be essential to the work of all scholars of the period.

H.R. Woudhuysen

At lunchtime on 4 October 2011 UCL Art Museum will be hosting a pop-up exhibition for which I am selecting works of art that started life as book illustration.

At lunchtime on 4 October 2011 UCL Art Museum will be hosting a pop-up exhibition for which I am selecting works of art that started life as book illustration. Close

Close

Yesterday I attended the

Yesterday I attended the  I’ve spent this week at the

I’ve spent this week at the