Reduced engagement in extra-curricular activities post-pandemic: should we be worried?

By Blog Editor, on 19 June 2023

COSMO researcher, Alice De Gennaro, considers the potential impacts of the dip in young people’s engagement with extra-curricular activities post-pandemic.

In our previous analysis, we documented the significant changes in extra-curricular activities that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that students from less advantaged socio-economic backgrounds re-engaged with extra-curricular activities to a much lesser degree, especially when looking at school type. Females were also less likely to re-engage with these activities and we look at the implications of this.

We also consider what might be the implications of such changes. In doing so we describe the association between continuing engagement in extra-curricular activities and young people’s health and wellbeing. We build on the analysis in the previous analysis and in our measure of continuing engagement we include those who never did any extra-curricular activities pre-pandemic to get a sense of a more general notion of extra-curricular engagement. A summary of this measure is illustrated below.

Figure 1. Continuing engagement (N=6,286)

We find that higher rates of continuing with extra-curricular activities and engaging with these activities at all are associated with lower rates of high psychological distress, better self-esteem and more physical activity. Higher frequency of physical activity is associated with better self-esteem and lower rates of high psychological distress, although only up to a threshold of five days exercise per week. We also look at associations of these findings with gender, to see how effects of reduced engagement may be distributed.

It should be noted that analysis here is descriptive and causality cannot be inferred for a number of reasons including bi-directional relationships (those with worse health/wellbeing are more likely to disengage from extra-curricular activities, as well as reduced extra-curricular engagement potentially being a risk factor for worse health/wellbeing) and the likely presence of other factors driving both more extra-curricular engagement and better health and wellbeing.

How is continuing extra-curricular engagement related to health and wellbeing?

To form a picture of the relationship between extracurricular engagement and health and wellbeing, we analyse several relevant measures of health and wellbeing: GHQ-12 scores, self-esteem scores, and levels of physical activity.

Evidence has shown links between extra-curricular activities and benefits for mental health. Another study found similar associations also during the COVID-19 pandemic. The figure below echoes these findings as rates of high psychological distress are higher among those who never did or stopped all activity. The proportion in the latter group was higher, which is suggestive that the association between engagement and mental health is amplified when people stop an activity, as opposed to never having done it. Rates of high psychological distress were lower among the respondents who started and continued with extracurricular activities, with proportions being only marginally different between those continuing with one to two activities and those who continued with three or more.

Figure 2. Continuing engagement in extra-curricular activities and GHQ-12 score (N=5,933)

While the GHQ-12 measure attempts to capture a general picture of mental health, here we can pull out a specific relationship with self-esteem that engagement seems beneficial. Evidence suggests that extra-curricular participation is linked to self-esteem. Following this, we look at the responses to an adapted Rosenberg self-esteem scale ranging from 0-15, 0 being low self-esteem and 15 being high. The average across the whole sample is 9.27 (N=11,464). The average scores among those who never did any activity and those who continued with no activities are similar at just under 9. The score then increases by almost half a point for those continuing with 1-2 activities and then by a full point for those continuing with 3 or more.

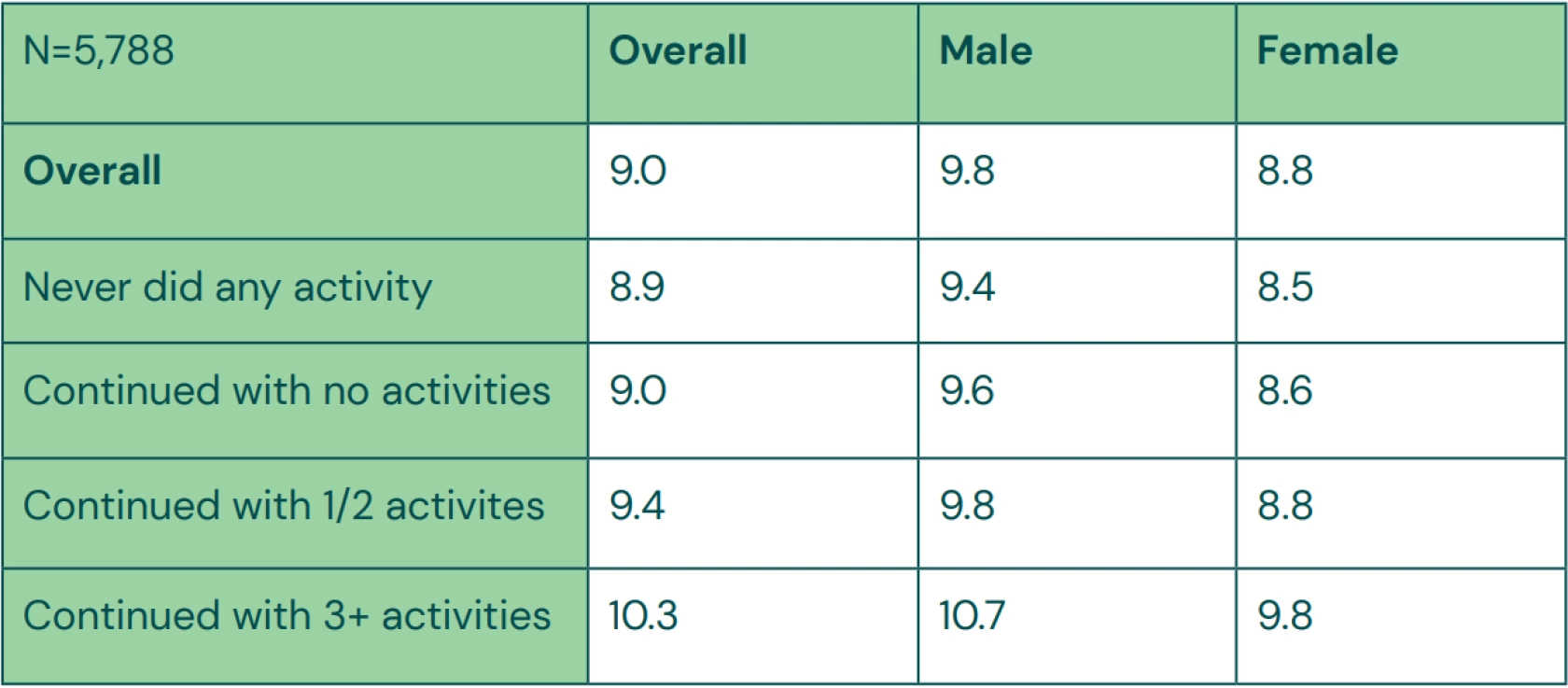

Given the lower extra-curricular engagement of girls it is useful to look further into self-esteem by gender. Overall, we find that boys had an average reported self-esteem score of 9.8. The average for girls was lower, at 8.8, and lower still for non-binary+ individuals at 6.5 (N=11,464). The table below splits these scores out by our continuing engagement variable, and we see the same pattern persist, with scores rising with engagement but with girls reporting lower self-esteem at each level. This is consistent with common findings that girls report lower self-esteem than boys. The findings below may be cause for concern that the reduction in extra-curricular engagement following the pandemic could harm young people’s self-esteem and perhaps more disproportionately that of girls.

Previous analysis found that females in this cohort had higher levels of high psychological distress and so considering this alongside the findings about self-esteem might cause further concern about the different engagement patterns by gender.

Table 1. Average self-esteem scores by continuing engagement and gender (N=5,788)

How much of a role does physical activity play in extracurricular engagement and wellbeing?

One way to look into students’ extra-curricular life, aside from their participation in specific clubs and activities, is to look at their self-reported days of exercise per week. This allows us to focus in on the fitness aspects of their life outside of school. While the pattern between extra-curricular activity and general health is nonlinear, looking at days of exercise can tease out a more specific form of health and its relation to extra-curricular activity.

We found a significant association between students’ weekly physical activity and their continuation in extra-curricular activities, as shown in Table 2. The more students engaged with extra-curricular activities, the more exercise they did per week, with those carrying on with three or more activities doing twice as much weekly exercise as those who never took part in extra-curricular activities. This suggests (as we might have expected) that extra-curricular activities are a major source of physical activity. Looked at from a slightly different perspective, among those who reported zero days of physical activity per week, over a third didn’t continue with any extra-curricular activities. This proportion was half as much for those who exercised every day of the week, affirming that reduced engagement in extra-curricular activities was quite a hit to the physical activity of students.

Table 2. Continuing engagement in extra-curricular activities and days exercise per week (N=3,742)

We find a U-shaped relationship between number of days exercise per week and elevated risk of psychological distress. The greater the number of days of exercise per week up to five days is associated with a lower proportion at elevated risk of psychological distress. However, rates of poor mental health then increase slightly as days of exercise per week increase further from five to seven days, although the proportion at risk is still far lower than those doing no exercise in a week. This inversion at the highest levels of physical activity might be capturing an externalising response to stress, where young people are exercising more to alleviate higher levels of stress. Alternatively, it could reflect some form of burden of exercising nearly every day while handling other aspects of their life, such as schoolwork and other responsibilities.

Figure 3. Weekly physical activity and % at elevated risk of psychological distress (based on GHQ-12 score) (N=7,319)

Physical activity may be a component in the link between extra-curricular activity and self-esteem. Reported self-esteem scores on average increase by around one point when students move from zero days (7.8) to one day (8.8) of exercise per week. Students who exercised for two or more days a week had higher self-esteem scores ranging from 9.2-9.9. A similar pattern persists among boys and girls, although girls start from a lower score. While these changes are small, they are not insignificant.

Given that extra-curricular engagement appears to be a major source of physical activity, the link between self-esteem and extra-curricular activities may be driven by the apparent boost to self-esteem that higher levels of exercise are associated with.

Conclusions

In this blog post, we have tried to unpack the relationship between extra-curricular engagement and pupil health and wellbeing. By looking across a variety of measures we can draw some conclusions. There is a small but significant association of extra-curricular engagement with lower levels of high psychological distress and higher self-esteem. We should not ignore gender differences here, as females not only had lower levels of engagement but reported lower self-esteem scores overall.

Looking further into physical activity, it appears that extra-curricular engagement accounts for a large amount of the exercise students do per week, suggesting that the decline in engagement during the pandemic would have made exercise frequency lower. More frequent physical activity is also associated with lower rates of high psychological distress up to a point, along with slightly higher self-esteem.

The findings in this analysis suggest that we should not underestimate the impact of a decline in extra-curricular engagement. We should consider not just how this engagement affects labour market potential but the personal aspects for young people, such as their mental health, self-esteem and physical fitness, especially bearing in mind the different patterns for boys and girls. Because pupils from more disadvantaged backgrounds engaged less with extra-curricular activities following the pandemic, we must acknowledge that any implications of reduced engagement on health and wellbeing will likely disproportionately affect these groups. We need to address the barriers that young people face to taking part in extra-curricular activities in relation to their socio-economic background and gender, so that we can keep young people feeling positive and healthy.

This is the second piece in a two-part analysis.

Close

Close