The Rise and Fall of the Adelphi

By the Survey of London, on 13 January 2017

Although little of it survives today, the Adam brothers’ innovative town-planning experiment at the Adelphi, off the Strand, of 1768–74, remains one of their best-known and admired works. Colin Thom of the Survey of London will give an evening talk on the theme of ‘The Rise and Fall of the Adelphi’ at Sir John Soane’s Museum on Monday 23 January 2017 – the first in a series of events to accompany the museum’s Robert Adam’s London exhibition. Here Colin provides a brief account of the Adelphi, which the Survey recorded at the time of its demolition in 1936. The results were published in Survey of London, volume 18, St. Martin-in-The-Fields II: the Strand (1937).

The Adelphi and the Thames riverside, looking east (engraving by Benedetto Pastorini, reproduced in the third (posthumous) volume of the Adam brothers’ Works in Architecture (1822)

The Adam brothers’ concept at the Adelphi is immediately striking for its monumentality and ambition. Here was an unprecedented attempt to create a large and entirely new district of elegant housing, raised up by some extraordinary engineering on a series of vaulted warehouses above the River Thames, on what had been an unfashionable, run-down stretch of ground known as Durham Yard.

Robert Adam’s genius lay in his ability to take and adapt elements of antique architecture and create from them something that was uniquely his own. At the Adelphi, his principal inspiration was the ruined palace of the Roman Emperor Diocletian at Spalato (modern-day Split, in Croatia), which he surveyed in 1755 as part of his Grand Tour and which formed the subject of a detailed monograph, published by Adam in 1764.

The remains of the sea front of Diocletian’s Palace at Split (engraving by Paolo Santini, Plate VII from Robert Adam’s Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia, 1764)

The similarities were evident. Both sites sloped down to the waterfront, hence both required embanking and the construction of vaults to create an even ground level above. The grouping of the long continuous frontage of the palace at Split along the shore, flanked by projecting towers at either end, is immediately recognizeable in Adam’s massing of the Adelphi blocks when seen from the river, with the central range of the best terraced houses – the Royal Terrace (later renamed Adelphi Terrace) – flanked by the ends of the lesser blocks of housing in the side streets leading to the Strand. In a characteristic Adam act of self-publicity most of the streets were named after the brothers – Adam Street, John Adam Street, Robert Street, &c.

Adam office design for the riverfront elevation of the Adelphi development (Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 32/10), and elevations of the sea wall of Diocletian’s Palace (Plate VIII from Adam’s Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian)

Robert Adam had been captivated by the transformation of the palace at Split into a bustling modern city, as well as by its Roman remains. This aspect he reinterpreted for London as a mixed environment of houses of several sizes and classes arranged in a grid of streets, along with shops, coffee houses, a tavern, hotel, Coutts’ bank, and a new Adam-designed headquarters for the Royal Society of Arts on John Adam Street – all underpinned by the cavernous wharves and warehouses. There was something undeniably Picturesque about the Piranesian sequence of dark vaults beneath the urbane streets of housing above.

The Adelphi vaults in 1936 (Historic England Archive photograph, AA65/00065)

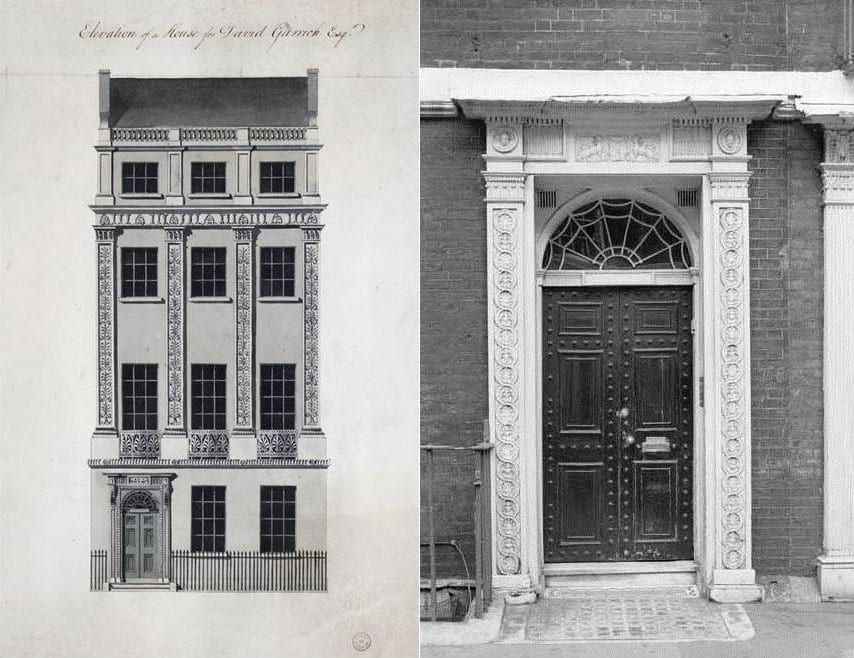

As originally built, the Adelphi houses showed the fine balance between ornament and plain surface at which Adam excelled, with relatively simple brick façades enlivened by ornamental stucco pilasters (emblazoned with honeysuckle motifs), entablatures, string courses, decorative doorcases and pretty iron balconies.

David Garrick’s House, Royal Terrace (Adam office elevation in Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 42/60), and a typical Adelphi doorcase at No. 9 Adam Street (Historic England Archive photograph, AA65/06112)

Though built as a speculation, the houses were decorated inside in the distinctive ‘Adam style’ familiar from his bespoke country and town house commissions, with decorative plasterwork to the walls and ceilings, and carved chimneypieces. The house at the centre of the Royal Terrace, taken by the actor David Garrick, a friend of the Adams, was especially fine, with painted panels by Antonio Zucchi incorporated into its main drawing-room ceiling, and a staircase with attractive bronze balustrading.

Adam design for the front drawing-room ceiling in David Garrick’s house (Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 13/30)

The Adelphi was begun at a time when Robert Adam’s star was in the ascendant. With a flourishing London practice and a succession of spectacular country house commissions behind him, he was Britain’s most fashionable architect; his Diocletian monograph had affirmed his status as a leading expert in the antique and in antique-derived Neoclassicism; and with his three brothers, John, James and William, he had recently established a London-based contracting and building supplies company – William Adam & Co. (which built the Adelphi) – echoing the family’s wide-ranging business interests in Scotland. But bold though the Adelphi was in its architecture and engineering, as a financial venture it was risky and impetuous, coming uncomfortably soon after the Adams had agreed with the Duke of Portland to build Portland Place on his estate at Marylebone – another ambitious town-planning commitment. They also had difficulty selling houses at their full valuation. Badly overstretched and with many properties unfinished, the Adams were forced to mortgage houses or sell them cheaply in order to raise capital to finish the development. Then a Scottish banking crash in the summer of 1772 tipped them to the verge of ruin. Though the sale of their assets by a private lottery saved them from bankruptcy, the brothers’ reputation had been tarnished, and they were never able to regain the heights of their earlier successes. The name Adelphi, chosen to immortalize the Adam ‘brotherhood’, also became a byword for over-reaching ambition.

The Adelphi survived in relatively good condition into the nineteenth century, though its immediate connection to the riverfront – such a fundamental element of the design – was lost when the Thames was pushed back and the Victoria Embankment and Gardens were created in front of it in 1864–70. Then in 1872, shortly after the lease had been renewed, heavy Victorian window dressings and a lumpy pediment were added to the Adelphi Terrace façade, disrupting its careful proportions. Also, by then the vaults beneath had become infamous as a haunt of the poor, the homeless and other outcasts of society.

Adelphi Terrace in the 1790s (from Thomas Malton’s A Picturesque Tour Through the Cities of London and Westminster, 1792–1801), and in 1901 (Bedford Lemere photograph in Historic England Archive, BL16618/001)

In 1927 the Adelphi estate was sold at auction, and in 1936 many of the houses, including the great riverfront terrace and its underground vaults, were torn down and a new Art Deco Adelphi building (designed by Collcutt & Hamp) erected in their place.

The remains of the demolished Adelphi Terrace, 1936, with buildings in John Adam Street beyond (Historic England Archive photograph, AA65/00065)

Today only a few runs of houses remain from the Adam development, in Robert Street, Adam Street and John Adam Street, including the beautifully proportioned Royal Society of Arts building, designed by Robert Adam.

Surviving houses in Adam Street, 2016 (Historic England photograph by Chris Redgrave) and Robert Adam’s pencil design for the elevation of the Royal Society of Arts building, John Adam Street (Sir John Soane’s Museum, Adam vol. 30/28)

Other fragments survive here and there, particularly in the Victoria and Albert Museum, including David Garrick’s front drawing-room ceiling, now incorporated into the British Galleries.

The ceiling from Garrick’s front drawing room in the V&A British Galleries. Photograph © Victoria and Albert Museum

You can read the Survey of London’s 1937 account of the Adelphi on British History Online here

Close

Close