Marylebone Literary and Scientific Institution

By the Survey of London, on 1 November 2019

The Marylebone Literary and Scientific Institution, which lasted from the 1830s to the 1860s, occupied a site on the south side of Wigmore Street, now covered by an office block backing on to Edwards Mews behind Selfridges. No trace of the building is left, but Grotrian Hall, the concert hall which originated as the institution’s lecture theatre, is still within living memory.

Marylebone in the middle third of the nineteenth century was firmly established as one of the richest, most fashionable parts of London, and with the Reform Act of 1832 became a Parliamentary borough with its own MPs. There was an extraordinary concentration of wealth, influence and talent in its streets and squares. So it is not at all remarkable that it should have started its own literary and scientific institution – such establishments were springing up in communities all over the country, middle and upper class counterparts to the equally popular working-class mechanics’ institutes. A little surprising, given its many distinguished members and supporters, and the high quality of its speakers, is that the Marylebone Lit & Sci should have flourished for such a relatively short time. The proximate cause of its failure was financial, but there seems to have been a general running out of steam in what began with a burst of energy, confidence and idealism at a time of some political optimism as well as ongoing technological and intellectual advance. At the start there was a strong emphasis on science, experimentation and discovery. Latterly the literary side came to dominate, comparatively unchallenging entertainment such as readings from well-known authors taking over from more demanding subjects. The original institution was always meant for both sexes, and an account of the inaugural meeting of 1835 refers to the biting asides of a learned but ‘ill-natured Bluestocking’ in the audience during Lord Brougham’s grandiloquent speech as patron.1 The final attempt to keep the institution going split it into two, one part nominally carrying on the original idea of learning and lectures (but literary not scientific), the other a conventional men-only club. Meanwhile the locality itself was changing in its social character, and the story of the institution and its building has links with this process, in particular with the redevelopment of one of the most notorious spots in Marylebone in the first half of the nineteenth century, Calmel Buildings, which stood behind Wigmore Street roughly where the western half of Edwards Mews now runs, more or less adjoining the institution itself.

Laid out and first built up in the 1770s, this end of Wigmore Street, west of Marylebone Lane, was originally named as two streets, reflecting landownership (link to Horwood’s plan of 1792–9). The western part, on the Portman estate, was Lower Seymour Street, and the rest was Edwards Street after the Edwards, later Hope Edwardes, family. This unnecessary distinction was eventually abolished in 1868, when the whole stretch became Lower Seymour Street, but it was not until 1923 that the further step was taken of merging it with Wigmore Street. As part of such an important thoroughfare connecting Portman Square and Cavendish Square, Edwards Street and Lower Seymour Street were good addresses, but the presence of Calmel Buildings must have been a continual nuisance to the residents on the south side. This court was an exclusively Irish, Roman Catholic enclave, possibly as far back as the late eighteenth century, and certainly by the early nineteenth century, when it was overcrowded, insanitary and violent. In 1810 a Frenchman staying in Orchard Street was kept awake all night by street-fighting in Calmel Buildings adjoining, and overheard two parish watchmen discussing whether to intervene – one saying ‘If I go in I know I shall have a shower of brick-bats’, the other replying ‘Well, never mind, let them murder each other if they please’.2 A few years later, giving evidence given to a Commons select committee on education, Montague Burgoyne, a well-off local resident who tried to set up a school in Calmel Buildings, referred to a recent murder there and described it as crowded with some 700 people in twenty-three houses and ‘upwards of a hundred pigs’.3 In 1831 it was recorded as consisting of twenty-six houses with a total population of over a thousand, and in 1845 investigators taking a census there witnessed two fights and a woman nearly beaten to death. When it was emptied for redevelopment in the winter of 1853–4, nearly 1,500 people were reportedly turned out into the streets.

In October 1833 Joseph Jopling, an architect and civil engineer, put forward a plan for the demolition of Calmel Buildings to make way for a public building with space for meetings, lectures and conversation, a library and reading rooms, recreation and refreshment rooms and even baths. The density of population there, he thought, ‘should not be permitted anywhere’ and the boxed-in site was in his view unfit for housing ‘even on an improved plan’. Jopling was living in Somerset Street, a now vanished street which ran just south of Calmel Buildings, where the painter George Stubbs had lived for most of his career, the site of which is now covered by Selfridges. Jopling’s paper4 opens with the statement that it had been selected to ‘commence a series of suggestions for the progressive improvement of Mary-le-bone’, and if this was not directly in connection with the actual Marylebone Literary and Scientific Institution it must have been done in full knowledge of its formation, which extended over several years.

The first that is heard of a Marylebone literary and scientific institution is the report of a prospectus being issued in 1831, and the project took shape the following year under the leadership of John Hemming, an ‘experimental and operative chemist’, still remembered for his work on the industrial manufacture of soda, who already lectured at the London Institution and who became the new institution’s first president. As Hemming recalled, the project ‘first beamed forth its infant scintillations around the parlour fire of a scientific neighbour, the ravages upon whose Turkey carpet could well tell, in a short time, the increasing numbers of the lovers of useful knowledge in the borough of Marylebone’.5 Who this neighbour was was not revealed. In Lower Seymour Street around this time were James Hope, a pioneer cardiologist, and William Spence, a noted political economist and entomologist; a short walk away Charles Babbage was already established at his house in Dorset Street. Wherever it began, the new institution found its home at what was then 17 Edwards Street, which had been the residence until his death in 1815 of Viscount Wentworth, a personal friend of George III and the uncle of Byron’s wife Annabella Millbanke. The house had recently been occupied by the Count and Countess Morel de Champemant. A substantial library was accumulated, subscriptions to newspapers and journals were taken out, a reading room and a chess room were fitted up, and a museum and a laboratory were planned. In December 1833 the premises opened with a first public lecture, on astronomy, given by the well-known scientific writer and speaker Dionysius Lardner.

The inaugural meeting of the Institution in March 1835, by T. M. Baynes (City of Westminster Archives)

Next year the Lord Chancellor, Lord Brougham, a keen promoter and supporter of such institutions, and a close associate of their pioneer George Birkbeck, agreed to act as patron. Extensive alterations to the house were made and a lecture hall for 600 was built. Crowded for an opening concert in February 1835, this proved gratifyingly ‘well-adapted for sound’ but oppressively stuffy. At the formal inauguration the next month, the skylight windows were consequently left open. As the speeches got under way there was a sudden squall, hailstones showered down and there were grabs for cloaks and umbrellas. Brougham, dressed for the occasion in a green frock-coat, black velvet waistcoat and grey and black checked trousers, rose to his feet with ‘Shut down the windows, I say, and let every Lady and Gentleman who likes it put on their hats and bonnets sans ceremonie’. Brougham went on to entertain the listeners with a two-hour speech, in which he set out the history of literary and scientific institutions and the urgent need for the education of the middle and upper classes. Without it, they would find the working classes rightly treading on their heels, challenging their position. ‘It was always his Lordship’s wish and earnest hope that the working classes to the lowest grade should drink deep of the well of science and of letters. The days were gone when the progress of knowledge could be stopped. The days were gone, too, when Gentlemen merely read a stupid newspaper article and Ladies spelled their way through the fashions of the month… In such a time it was no wonder that the servant could read neither the one nor the other. It was laughable to look back at those venerated times when the majority of country Gentlemen knew very little more than the horses they rode or the wild animals they chased; and when, if the names of Bacon, or Locke, or such a one as Bentham, were mentioned in their baronial halls, it would be imagined that they were the names of so many horses’.6

The new institution fully reflected Marylebone’s elevated social and intellectual character, and was always aimed at the middle classes and above, for whom the annual subscription of two guineas was modest. Prominent names involved in its formation or early development included Edward Wedlake Brayley, the topographer; the distiller Sir Felix Booth, who financed his friend John Ross’s arctic explorations; the traveller and writer James Silk Buckingham; Sir Anthony Carlisle, surgeon and anatomist; James Copland, physician; Raikes Currie, the banker and politician; John Cam Hobhouse, the politician, Byron’s friend and executor; the lawyer Sir William Horne, Brougham’s associate and MP for the new constituency of Marylebone; the law reformer Basil Montague; and the surveyor and geologist Richard Cowling Taylor. Hemming was in time succeeded as president by the Oxford Street pharmacist and collector of Landseer’s paintings Jacob Bell, and Bell after his premature death by the Anglo-Jewish community leader Sir Francis Goldsmid. Sir Robert Peel, Lord Broughton and the art patron Henry T. Hope later became vice-presidents. Early lecturers included the antiquary and topographer John Britton on castellated architecture, Lardner on Babbage’s calculating engine, Benjamin Humphrey Smart on elocution, and Thomas Southwood Smith on ‘animal economy’, a melange of physiology and embryonic psychology. Subsequently, speakers included Peel, on poets, and the composer Charles Kensington Salaman.

Another well-received speaker in the mid-1850s was Cardinal Archbishop Wiseman, a resident of York Place (now part of Baker Street) who lectured on the effect of words on thought and civilization, and later on the collection and arrangement of paintings for a national gallery. A few years earlier, in 1851, Wiseman had stood on a platform in Calmel Buildings before an Irish crowd put at 3,000, denouncing the local non-denominational ragged schools. These and their associated social work were one response to the squalor and violence of not just Calmel Buildings but other impoverished courts and streets in the area. Nearby Gray’s Yard Ragged School, begun in 1836, was a particular success, carrying on well into the twentieth century, with a gospel hall and hostel.

Around the time Wiseman lectured at the institution, Calmel Buildings was finally being replaced – by the Anglican church of St Thomas, opened in 1858, a project which owed much to the efforts of John Pelham, the evangelical rector of Marylebone, subsequently Bishop of Norwich. The erection of this church, it was suggested, somewhat ludicrously given that they were Roman Catholic, might prove the reformation of the erstwhile inhabitants. The church was allocated a district extending from Portman Square to Cavendish Square, and offered such a good stipend that when the incumbent died in 1891 more than 600 applications for the post were received in a week. Schools were built in the 1860s, and a mission and soup kitchen set up near by for the local poor, and in time St Thomas’s became a rather fashionable church, known for high-society weddings. Churchwardens included the decorator J. D. Crace, and Florence Nightingale rented seats there for her servants.

The area c.1870 (Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland)

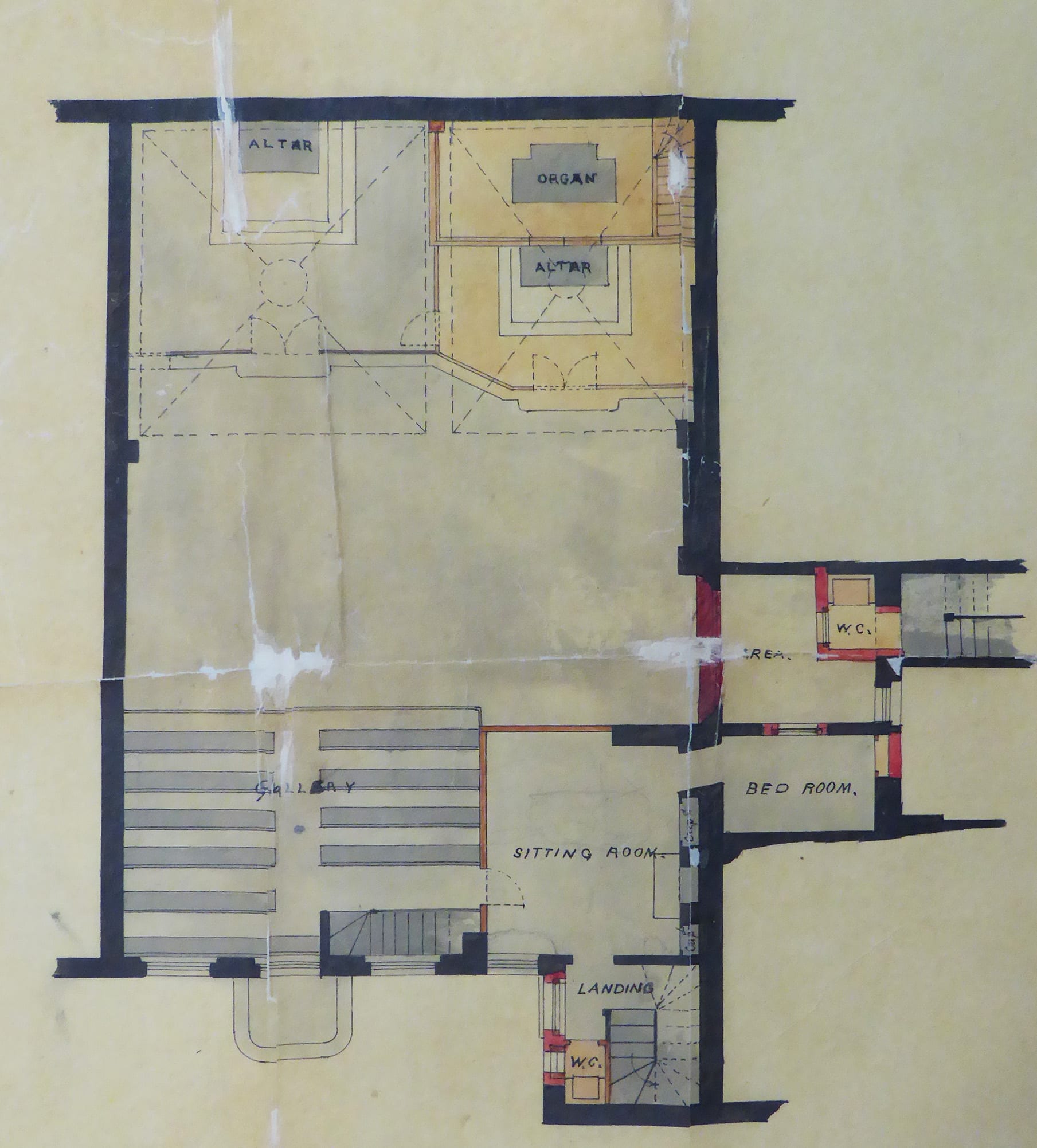

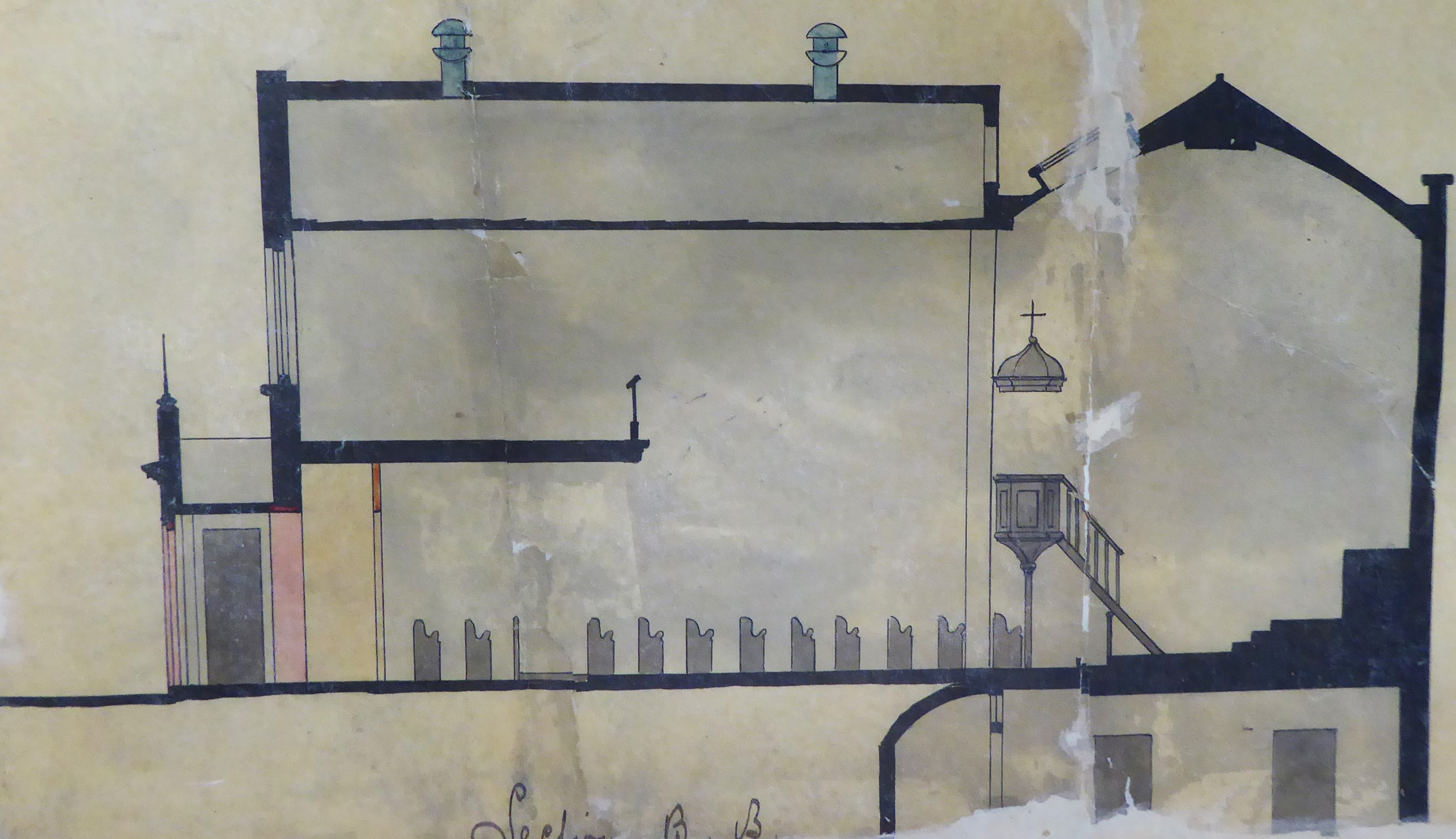

The Literary and Scientific Institution did not own 17 Edwards Street, but rented it from an Oxford Street upholsterer, John Balls, whose ‘liberality and philanthropy’ were duly acknowledged at the 1835 inauguration. It was responsible for repairs as well as rent, and in 1846 a fund was launched with the aim of building rent-free premises on a larger scale. Brougham gave £100, and others, including Sir Benjamin Hall and Sir Charles Napier, contributed. Although the plan did not succeed, in 1851 the existing lecture hall was enlarged and remodelled, with a gallery, so that there was now room for 1,000. Underneath were fitted up various ancillary rooms including class-rooms and retiring rooms for lecturers. The theatre opened with Macbeth read by the actress Isabella Glyn.

Finances fluctuated, with periods of debt and falling membership. Besides rent and repairs, the cost of getting top speakers was high. In 1852 Thackeray, who gave many talks at the institution, was paid £150 for six lectures on English humorous writers, already given at Willis’s Rooms, while in 1860 a too-high admission fee was blamed for empty seats at Louis Blanc’s lecture on Parisian fashions in the eighteenth century. A crisis of debt led to the institution’s reorganization in 1864 under new management as the Marylebone Literary Institute and Club. Referring to the great clubs of St James’s and the proliferation of working-men’s clubs, a supporter demanded, where were the clubs for the middle class? ‘They nowhere exist. But are they not needed?’ Membership of the ‘Literary Department’, as in the original institution, was open to ladies and gentlemen; the club, ‘of course’, was for men only. The lecture theatre was redecorated, and rooms were fitted up for smoking and billiards.7

The new regime did not last more than a few years, and the staging of readings from Scott by an obscure speaker indicates the level of decline. When the actress Fanny Stirling gave dramatic readings at the hall in 1870 it was for a new organization, the New Quebec Working Men’s Club, later the Quebec Institute, a self-improvement venture for men and women based on the Birkbeck Institution, with which Mrs Stirling, the Earl of Lichfield, Lord Lyttelton, and other local figures including the Presbyterian minister Donald Fraser and Oxford Street decorator Peter Graham were involved. Among the speakers in 1876 was Anthony Trollope, on reading. During this period the lecture theatre was hired out as Seymour Hall for public meetings and concerts – Father Ignatius the monk of Llanthony Abbey being one well-publicized turn. In 1878 the Quebec Institute closed or moved away, and the premises were taken over by the American piano makers Steinway as their first London Steinway Hall.

The area in the 1890s (Reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland)

Despite the clearance of Calmel Buildings, the area retained a considerable Irish Roman Catholic population, and several houses adjoining the hall became a convent and mission run by the Order of St Vincent de Paul. This was initiated by Mary Teresa, Lady Petre, wife of the 12th Baron Petre, whose London residence was then in Portland Place. Lady Petre had set up a French-style crèche near Marylebone High Street in the 1860s, and later a home for destitute girls off Marylebone Lane. In 1873 she conceived the idea of a ‘Night Home’ for working girls, to serve as a memorial to the pilgrimage that year by English and Irish Catholics to the shrine of the Sacré Coeur at Paray-le-Monial in Burgundy. The home was opened in 1878 by Cardinal Archbishop Manning in a remodelled house a few doors from the old Literary and Scientific Institution. More houses were annexed in subsequent years, including that adjoining the hall, occupied since 1858 by another charitable institution, the Samaritan Free Hospital for Women and Children. By this time the Catholic establishment included an orphanage and a school for girls and infants. Steinway Hall itself was eventually acquired, with plans to turn it into an assembly hall when Steinway’s lease ran out in 1920. Ultimately these plans were superseded, and in the 1938 the whole establishment moved into new purpose-built premises in Blandford Street, where the school remained until some years ago.

Steinway Hall was transformed in 1925 for new occupants, the piano makers Grotrian-Steinweg, ‘by the complete removal of several awkward architectural features, a number of which were an eyesore’.8 As Grotrian Hall, it was considered as comfortable as any music venue in London, and for certain ‘concerts of an intimate character’, the best.9 Its closure in 1938, the departure of St Vincent’s, and the demolition of St Thomas’s a few years before were all on account of Selfridges. Harry Gordon Selfridge had wanted to extend his store up to Wigmore Street and spent years piecing together the site, a patchwork of leasehold interests taking up the whole block from Orchard Street to Duke Street. After the war Selfridges decided the land was not all needed after all, and having acquired the entire freehold, sold off the Wigmore Street frontage for redevelopment. In 1955–7 three matching office blocks, designed by the architect Cecil Elsom, were built there for a consortium including Metropolitan Estate and Property Corporation, letting to such names as IBM and 3M. This was one of the biggest office developments London had yet seen. The whole site has been redeveloped again in recent years.

References

- Morning Post, 5 March 1835

- {Louis Simond}, Journal of a Tour and Residence in Great Britain during the years 1810 and 1811, vol. 2, Edinburgh 1815, p. 259

- Report from Select Committee of the House of Commons appointed to inquire into the education of the Lower Orders of the Metropolis, 1816, pp. 461–2

- City of Westminster Archives Centre, D. Misc 197

- Morning Post, 5 March 1835

- Morning Post, 5 March 1835

- Marylebone Mercury, 2 January 1864; 3, 10 September 1864

- Aberdeen Press and Journal, 1 October 1925

- News Chronicle, 8 April 1938

Close

Close