All Saints’ Church, Margaret Street

By the Survey of London, on 25 December 2015

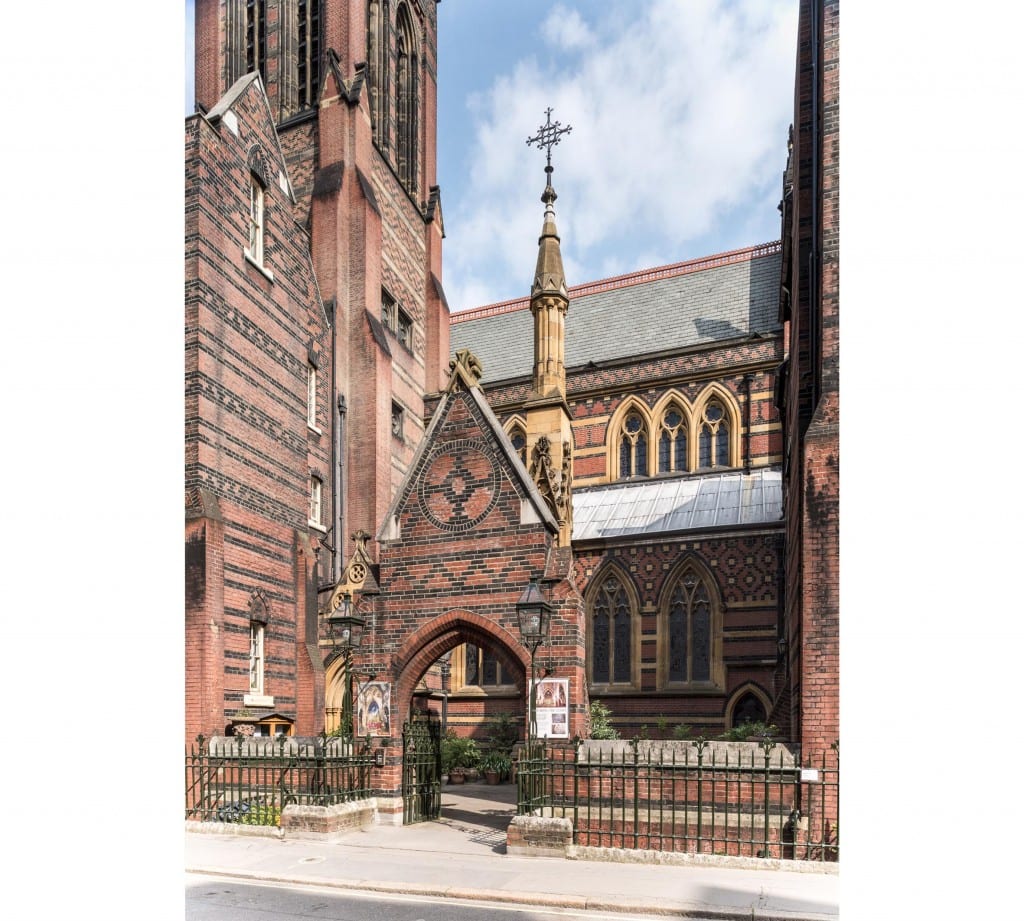

The brick church and lofty spire of All Saints, together with the twin clergy and parish buildings that front it towards Margaret Street, comprise a renowned monument to Victorian religion and architecture. Exuberant and compact, the group was built in 1850–2 by John Kelk to designs by William Butterfield, yet the interior of the church with its painted reredos by William Dyce was not completed and opened till 1859.

Generally regarded as Butterfield’s masterpiece, recent restorations have reinforced his original vision of strength, experimental colour and sublimity. A full account of this astonishing church will be given in the Survey of London’s forthcoming volumes on South-East Marylebone, in the meantime we would like to share a few of the extraordinary photographs of the church, taken for us by Chris Redgrave between 2013 and 2015.

A view of the Margaret Street frontage of All Saints’ Church and its twin clergy houses, showing the 220ft spire (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave). If you are having trouble viewing images, please click here.

All Saints replaced an earlier chapel that had been built in the mid eighteenth century and by 1839 was ‘a complete paragon of ugliness … low, dark and stuffy … choked with sheep pens under the name of pews’ and ‘begirt by a hideous gallery, filled on Sundays with uneasy schoolchildren’. [1]

The entrance arch to the church, in red brick with diaper patterns in black brick (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

In 1846–7 the old chapel was embellished and restored by William Butterfield, but this was just an interim measure before plans for a new church could be put in hand. Butterfield was selected as the architect for the new church. Aged then 34 and at the top of his powers, he was to remain architect to All Saints and a member of the congregation until his death in 1900.

The Clergy House on the east side of the church, now offices (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The building contract was signed on 1 September 1850 and despite the site constraints, the construction of this radical and unique church went ahead smartly, so that the shell was finished by the end of 1852. For six and a half further years the church stayed shut. All the available money had been spent, and there were differences over how to finish the interior.

View towards the east end with the elaborately patterned chancel arch. (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The church was consecrated at last in May 1859, after an estimated total expenditure of £70,000. All Saints opened to much publicity in newspapers, church journals and the building press alike. The Prince Consort, always interested in art-novelties, was among early visitors. Most comment was complimentary, sometimes lavishly so.

The chancel and towering reredos with paintings by H. A. Bernard Smith to designs by Ninian Comper, 1909, recreating William Dyce’s reredos of 1854–9 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The pulpit. Seven-panelled on a splayed base, front supported on stubby granite columns, faced in patterning of many marbles, c.1858 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

All Saints, Margaret Street, by common estimation a masterpiece of British architectural and ecclesiastical art, has drawn many levels of reaction. Ian Nairn likened the church to an ‘orgasm’, and Nikolaus Pevsner saw it as an endeavour ‘most violently eager to drum into you the praise of the Lord’. [2]

North wall of the tower at the west end of the nave, with memorial to Henry Wood in the arch depicting the Ascension, 1891 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

All critics have agreed on the buildings’ sheer impact, expressed through force of line and intensity of colour. This ‘architecture of power’, to borrow Ruskin’s phrase, can be felt as strongly today as it was when the church was new.

Nativity with six apostles on the lowest row of the reredos. The tilework at All Saints was designed by Butterfield, painted by Alexander Gibbs and executed by Henry Poole & Sons (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Sources

- Peter Galloway, A Passionate Humility: Frederick Oakeley and the Oxford Movement, 1999, pp.45–6 (quoting from Oakeley’s memoirs in Balliol College Library, Oxford)

- Ian Nairn, Nairn’s London, 1988 edn, p.77: Susie Harries, Pevsner and Victorian Architecture Studies in Victorian Architecture and Design, vol.5, 2015, p.29. See also James Stevens Curl, ‘All Saints’, Margaret Street’, in AJ, 20 June 1990, pp.36–55

Close

Close