Toynbee Hall in the 21st century

By the Survey of London, on 31 January 2019

Toynbee Hall is currently undergoing a transformation of its buildings, but the 135 years that it has stood on Commercial Street, Whitechapel, have seen constant change and evolution. The distinctive Tudor-style block at its heart was the original building, built in 1884 as the first university settlement, whose driving force was Samuel Barnett, vicar of the adjoining St Jude’s church (demolished in 1925), and his wife Henrietta. Their aim in establishing the settlement was to break down class barriers, in the belief that it was the duty of the fortunate, educated middle classes to share the benefits of their education with the less fortunate, to enable them to realise their ‘best selves’, and as a lubricant to mutual understanding between the classes. If the idea was to bring the poor of Whitechapel and the enthusiastic young men of Oxford and Cambridge together, the building that went up in 1884 was definitely more in the Oxford mould.

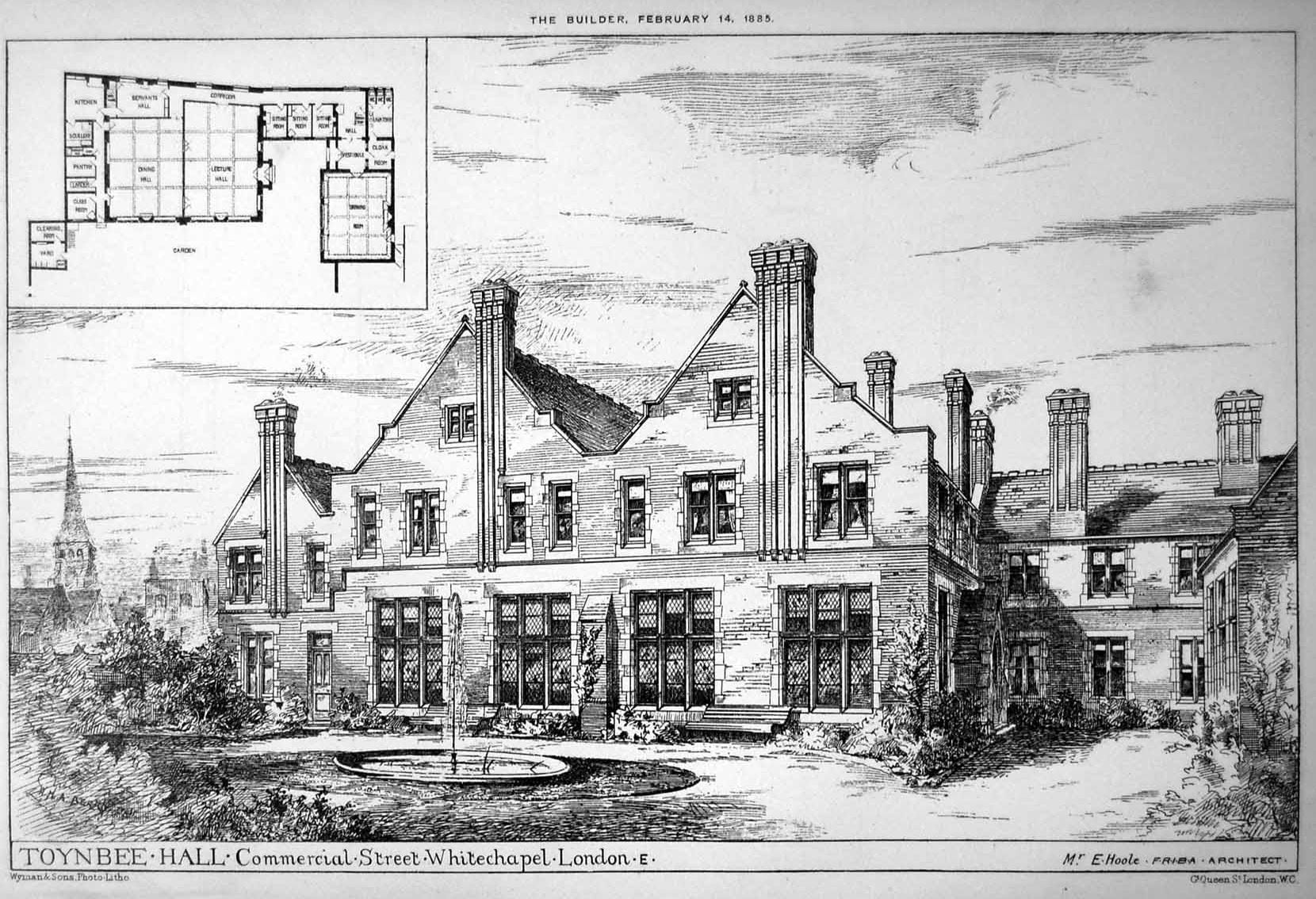

Toynbee Hall elevation and plan, from The Builder, 14 Feb 1885

The frontage of Toynbee Hall, with the original entrance, left, and the new entrance, centre, in March 2018. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

The Hall, to the designs of Elijah Hoole, with steeply pitched gabled fronts in warm red brick with Box-stone dressings, stone-mullioned and transomed leaded-light windows and assertively tall ribbed chimneys, was, in Samuel Barnett’s view, ‘a manorial residence in Whitechapel’,[1] but what it resembled more, especially with the sense of enclosure provided by the gatehouse and the warehouses fronting Commercial Street, was an Oxford college.

The main block housed a lecture room and dining hall, and the ‘settlers’ had rooms above them, some two-room sets, others bedsitters, surrounding a central common room lit from dormers in its pitched roof. A large drawing room in its own pitched-roof building was built alongside. The interior of Toynbee Hall reflected the tastes and ambitions of its founders. The drawing room was furnished in a mix of Aesthetic and Arts and Crafts styles, with improving prints and sculpture, the leaded windows draped incongruously in rich curtaining: ‘we … decided to make it exactly like a West End drawing room, erring, if at all, on the side of gorgeousness’. The students’ rooms were more simply furnished but ‘in all rooms neutral drabs were abolished: Whitechapel needed lovely colours’.[2] The staircase at the south-east corner was an especial tour de force, the balusters composed of circular fretwork discs of twining leaves.

The main staircase at Toynbee hall as restored in 2017. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

The restored lecture room of Toynbee Hall, with the original entrance door, left, and panelling added in 1890. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London, March 2018

The restored Ashbee Room, formerly the dining room, at Toynbee Hall, with decorative roundels and plaster coats of arms added by C.R. Ashbee and his students in 1887. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London, March 2018

The building was opened by the Prince of Wales in January 1885 and soon a wide array of classes in history, economics, literature, chemistry, botany and languages were being offered, along with reading groups and ‘conversaziones’, entertainments, sports clubs and social events where settlers could invite four ‘pals’ each into the collegiate dining room. The fees – from 1s – did not preclude anyone but the very poorest, and evening classes were held for those who had work to attend to during the day, but the level of the teaching, which soon included university extension classes, was aspirational.

College Buildings elevation, from The Builder, 13 Nov 1886

Toynbee Hall was only one weapon in the Barnetts’ armoury of attack on poverty in Whitechapel. For the Barnetts the material, moral, educational and social welfare of the poor were indissolubly interconnected issues. Soon after Toynbee Hall opened, College Buildings, a block of ‘industrial dwellings’, also designed by Hoole, and in a similar style was built adjoining the Hall’s site on Wentworth Street, with flats aimed at a range of tenants from the poorest to skilled artisans, and with one wing set up as a student hostel.

Over the following 130 years Toynbee Hall’s aims and methods evolved as approaches to social work and education shifted, with the state taking over many roles previously fulfilled by philanthropy. Under the energetic wardenship in 1919–54 of J. J. Mallon, ‘the most popular man east of Aldgate Pump’, initiatives on sweated labour, public order, education and hire purchase influenced several Acts of Parliament. But it was Mallon’s cultural interests, reflected in increased music, dance and drama activities in Toynbee Hall, that drove the alterations and extensions to the buildings, which were showing their age by the 1930s.

The auditorium of Toynbee Theatre with murals by Clive Gardiner. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London, December 2018

Mural of Pegasus and Athena, 1939, by Clive Gardiner, in Toynbee Theatre. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London, December 2018

Detail of The Furies mural of 1939 by Clive Gardiner at Toynbee Theatre. Photograph by Derek Kendall for The Survey of London, December, 2018

A large modern building – Toynbee Theatre, now known as Toynbee Studios – went up behind Toynbee Hall in 1939. Built to the designs of Alister MacDonald, son of the former Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, it provided a 400-seat theatre, with murals of The Furies and Pegasus and Athena by Clive Gardiner, and a room used variously as a music room and children’s courtroom (to offer a less intimidating environment to young offenders). Toynbee Hall narrowly escaped total destruction during the war. The street frontage in Commercial Street was destroyed along with the warden’s lodge and library, to be replaced after the war by a sunken garden, later called Mallon Gardens.

The former music room and children’s court room at Toynbee Theatre. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London, December 2018

An important event in the stabilisation of Toynbee Hall as an institution was the arrival as a volunteer in 1964 of John Profumo, the former Secretary of State for War, who had resigned the previous year over a sexual scandal. Profumo energised fundraising and secured Toynbee Hall’s future, with promises of £150,000 by 1967. In 1965–7 a new building to the designs of Martin and Bayley, architects, incorporating offices and a warden’s flat, and accommodation for ‘junior residents’, adolescents recently arrived in London, was finally built on the site of its bombed predecessor. First known as The Gatehouse, this was renamed Profumo House in 2006.

By the early 21st century the Toynbee Hall estate was again showing its age. In the 1970s ‘respectful but dull’ blocks,[3] Attlee House and Sunley House, with flats and lecture rooms had been built alongside Toynbee Hall, and a decade later College Buildings were rebuilt as College East, replacing all but one incongruously maintained Gothic bay from its old frontage. But Toynbee Hall was also questioning the financial viability of its wider activities, in the context of a historic inner London building, Grade II Listed since 1973, surrounded by buildings that had accrued piecemeal in the second half of the 20th century.

The single bay of College Buildings, retained when that building was demolished in 1984, seen here in June 2017 when College East, the replacement building was itself demolished for the redevelopment of the Toynbee Hall estate. The retained bay of 1886 has since been reincorporated into the facade of the new flats. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

The decision was made in 2013 to redevelop the estate at a cost of £17m, partly by a partnership with a private developer, to take a lease on the sites of Attlee and Sunley Houses and College East, and rebuild them as mixed tenure housing and offices. The scheme is forecast to enable Toynbee Hall to increase the number of those it can assist, with legal and debt advice, wellbeing (notably for the elderly) and education by fifty per cent, to 20,000 a year.

The restored and extended Toynbee Hall, left, with new flats – ‘Leadenhall’ and Billingsgate’ in the distance and ‘Broadway’, right. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London, December 2018

The first works in 2016–18, to the designs of Richard Griffiths conservation architects, were to Toynbee Hall itself, restoring the fabric, notably Hoole’s leaf-roundel staircase balusters which had shed a lot of leaves over the years, and adding a two-storey addition in brick matching the original building, its new east elevation presenting four striking double-pitched gables with bronze-finish zinc cladding. In the course of works murals of 1932 on the theme of the arts and sciences in a pastoralist manner reminiscent of Stanley Spencer, by Archibald Ziegler, commissioned by J. J. Mallon, were rediscovered in the lecture room – the boards he had painted them on had simply been turned round and reused, probably in the 1960s when their style was unfashionable, and there are plans to restore and reinstall them.

Archibald Ziegler, Literature mural of 1932, from the Illustrated London News, 24 Dec 1932

The new entrance hall, left, created within the former student sitting rooms of Toynbee Hall, and the new top-lit corridor linking the original building and the new rear building. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London, March 2018

The new flats, to the designs of Platform 5 and David Hughes, architects, once again retain part of the College Buildings frontage. In keeping with Toynbee Hall’s ethos, though increasingly unusual in mixed-tenure developments, the affordable housing (14 flats out of 63) is integrated into the scheme. The names of the blocks – Leadenhall (Attlee site), Billingsgate (College East) and Broadway (Sunley) – however, indicate the City-focused aspirations of the developer. Mallon Gardens is being landscaped level with the street for the first time ‘as the centre of a model urban village with a strong physical and visual relationship to the heritage asset and the wider Toynbee Estate’.[4] Toynbee Hall reopened in 2018 and the flats are scheduled to complete later this year.

1. London Metropolitan Archives, F/BAR/6

2. Henrietta Barnett, Canon Barnett: His Life, Work and Friends, London 1918, vol. ii, p. 42

3. Bridget Cherry, Charles O’Brien and Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England, London 5: East, 2005, p. 398

4. ‘Toynbee Hall Masterplan’ from Richard Griffiths Architects, ‘Toynbee Hall E1’, design and access, community consultation and landscape design statements, June 2014, p. 9, via Tower Hamlets planning applications online

Close

Close