The Baker Street Bazaar

By the Survey of London, on 14 June 2019

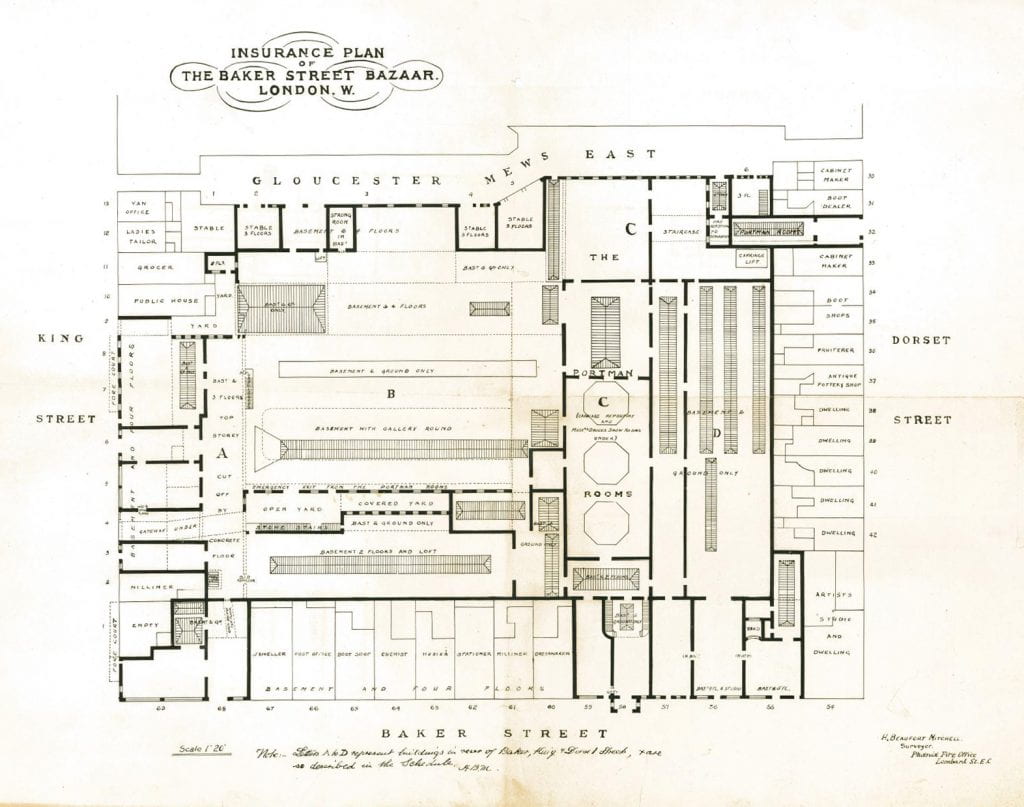

The Baker Street Bazaar was a group of buildings hidden behind houses and shops on the west side of Baker Street, between Blandford Street and Dorset Street. It was a famous place in Victorian times and well into the twentieth century, but the name was going out of use before the Second World War and what now seem to have been the great days of the establishment were by then long over. Burned out in the Blitz, the Bazaar was demolished in 1941 and its site became an American military car-park. In the 1950s it was redeveloped with the head offices of Marks & Spencer, coincidentally the pioneers of Penny Bazaars half a century earlier. Marks & Spencer moved there in 1957 from scattered offices, including those across the road at 82 Baker Street, where the company had been for many years. This was a time when important sites in Baker Street and elsewhere in this part of the West End were being redeveloped with corporate headquarters. Marks & Spencer’s were the biggest, and there was space for part to be let at first to another corporation, Metal Box, for its own offices. The buildings, known until Marks & Spencer’s departure in 2004 as Michael House, are still there but hardly recognizable following enlargement and remodelling by Make Architects in 2005–8, as 55 Baker Street.

In their origins, the blitzed buildings were neither a bazaar nor even in Baker Street. When the district was first laid out in streets, two of the main developers were Abraham Adams, originally a carpenter, and Thomas Elkins, a bricklayer. In 1771 they entered into agreement with the landowner Henry Portman for one particularly large site, with a plan involving a market square on the east side of Baker Street. Ten years later, the market having failed to appear, most of the ground had to be handed back to Portman. But a certain amount of work had been done round about, including one development still under construction. This was a barracks for the Second Troop of Horse Guards, one of several cavalry barracks called into being by the Napoleonic wars and conveniently close to Hyde Park. It seems that in the end Adams and Elkins had to give up the barracks too, for in 1791 Portman leased it to George and John Elwes, sons of the financier and legendary miser John Elwes, who were able to relet it to the government on lucrative terms. By that time, the occupying troop had been reformed as the Second Regiment of Life Guards, with men of lower social background replacing the previous complement of ‘gentlemen troopers’.

Quadrangular in layout, with a central parade ground and a riding house at the north end, the barracks was entered by passageways from the street on the south side, then King Street and only redesignated as part of Blandford Street in 1937.

The Horse Bazaar (Westminster Archives)

In 1821 King Street Barracks was replaced by a new barracks in Regent’s Park, and in 1822 reopened as the Horse Bazaar, the latest venture by the businessman and politician John Maberly. He had managed to get the premises at half the rent the government had paid, but was pouring money into the place. Maberly’s was a coachmaking and leather-dressing family, and he had married the daughter of William Leader, the Marylebone-based coachmaker to the Prince of Wales. With a fortune inherited from Leader, he plunged into manufacturing, contracting and finance, setting up banks and a soapworks, acquiring textile mills and supplying the army with uniforms. As an MP from 1816, for Rye and then Abingdon, he was a vociferous advocate of tax reform. At Shirley House, his seat near Croydon, he maintained racing stables. Maberly’s businesses were largely sound enterprises, but he became heavily involved in stock-market speculations and risky overseas loans. In 1832 his bank John Maberly & Co. suspended payments, and within weeks he was bankrupt. Only a fraction of his debts was ever paid off. He died abroad in obscurity some time later, but his son William Leader Maberly was able to pursue a successful career in the army and civil service, running the Post Office before Rowland Hill took over and living near his father’s Bazaar, in Gloucester Place.

At first the Bazaar was just for sales of horses on commission, but soon the business expanded, as carriage sales were introduced, advances were made on horses and carriages brought for sale, and harness and saddlery was sold. When it opened, it was described simply as comprising 300–400 stalls, with a large riding house and high-walled exercise ground – much as it must have been as a barracks. But subsequently it is clear that a great deal was spent. Accounts vary, but it was in the tens of thousands of pounds. There were light and spacious galleries capable of displaying 500-plus carriages, and the auction room itself was a top-lit hall with an elegant viewing gallery. Most expensive, no doubt, was the vast and lavishly decorated ‘Subscription Club’ room built over the riding house. This was once thought to have been the former officers’ mess, but it was too grand even for a guards’ regiment. It proved too grand even for the Subscription Club.

Although the word bazaar had been in use from the start, it was only with the opening of the ‘New Bazaar’ in 1826 that the establishment took on the character of a general retail market, aimed at the most fashionable and affluent shoppers. Encouraged by sales of tack, Maberly launched this fresh development based on John Trotter’s Soho Bazaar. Applications for stalls were sought from independent traders, and provision was made for the sale of furniture, pictures and other articles on commission, on which, as with carriages, advances were offered. A vast range of goods was promised, ranging from watches and jewellery to perfumery and toys. The furniture department was at the King Street end, while dozens of stalls comprising the Ladies’ or Fancy Bazaar occupied the gallery floor of the long eastern range. A house in Baker Street was acquired to form the entrance, and so the site in due course acquired its memorably alliterative name. At the north end the former Subscription Club room, renamed the Great Room, was fitted up with more stalls. Ante-rooms included one displaying glassware, one for music, another serving as a dressing room for ladies buying millinery. Refreshment rooms, reading rooms and private subscription rooms completed the ambience of leisure and luxury, while the female stallholders had ‘a more than ordinary share of youth and beauty’. According to an old story, Thackeray based Becky Sharp on Tizzie Reeves, an adventuress whose mother was one of these girls. ‘When these alterations are completed,’ it was claimed, ‘there will be assembled, under one roof, the most extensive collection of the luxuries, necessaries, or conveniences of life, probably to be met with in Europe; presenting the nearest approach we have yet seen to that Eastern market, from which it has taken its title’. [1]

The auction room at the Horse Bazaar (Westminster Archives)

With Maberly’s bankruptcy, the Bazaar was bought by the auctioneer Matthew Clement Allen, proprietor of Aldridge’s Repository, the horse and carriage mart in St Martin’s Lane. Allen’s brother-in-law William Boulnois, a City wine merchant, became involved, and in time took over parts of the premises, including the carriage and furniture departments. Horse sales were transferred to Aldridge’s in 1838, after which Boulnois had the whole Bazaar to himself.

Born to a French emigré family, Boulnois became squire of Gestingthorpe in Essex, where he died in 1862. Thereafter the Bazaar was run in partnership by two of his sons, William Allen Boulnois, architect and surveyor, and Edmund, who became a prominent figure in Marylebone as a businessman and in many public roles, including JP, Guardian of the Poor, LCC member and Conservative MP. Percy Boulnois, another brother, became the borough engineer of Portsmouth and a close friend of Arthur Conan Doyle. As Doyle’s biographer Andrew Lycett suggests, although the Bazaar never figures in the Sherlock Holmes stories, the Boulnois connection may have prompted the choice of Baker Street as Holmes’s address.

In 1840 William Boulnois announced the opening of an ironwork department, grandly called the Panklibanon. Manufactories on site were to permit the undertaking of contracts ‘of any magnitude’. [2] Unfortunately, all this was in breach of a covenant in the head lease against noxious trades. The new forges had to be dismantled and the manufacturing side of the business abandoned. Consequently the Panklibanon was reduced to showrooms only, with a range of goods from stoves and baths down to pans and tea trays. It passed through a succession of proprietors, before being taken over as the lighting and glassware showrooms of Apsley Pellatt.

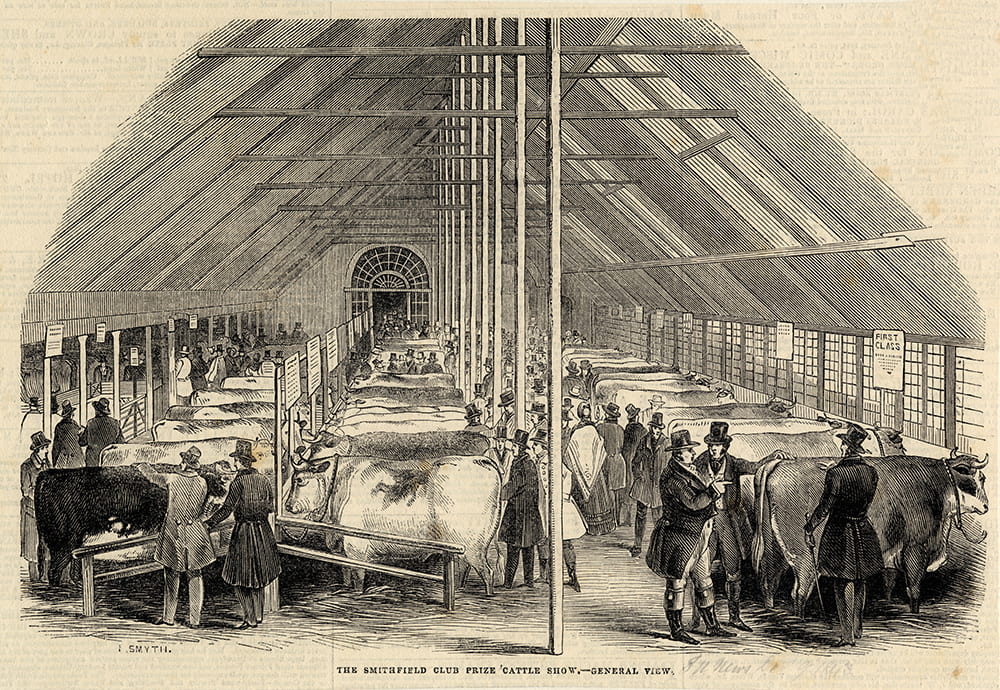

The Bazaar’s use for exhibitions went back at least to 1827, when George Pocock’s experimental kite-powered carriage, the Charvolant, was put on display. After horse sales were given up it became an important venue. The Smithfield Club, founded in 1798 under the Duke of Bedford’s presidency to improve livestock standards, held its annual show there from 1839. Boosted by the development of the railways, which enabled animals to be brought from afar, this was a pre-Christmas extravaganza of grotesquely overfed cattle, sheep and pigs combined with displays of the latest advances in farm equipment, and it was enormously popular and prestigious.

Smithfield Club cattle show in 1843 (Westminster Archives)

At first it was makeshift, with a temporary canvas roof and the ground so filthy that ladies in their long skirts were unable to attend. Later, improvements were made including a permanent iron-framed roof built to W. A. Boulnois’s design. Prince Albert was a regular exhibitor, and he and Queen Victoria visited on several occasions; red sand was put down in the show-yard. But the show outgrew the Bazaar, and from 1862 was held at the new Royal Agricultural Hall in Islington.

More important even than the Smithfield show was the waxworks exhibition of Madame Tussaud and Sons, which moved in 1835 from the Royal London Bazaar in Gray’s Inn Lane to the Great Room at Baker Street, where it would remain for half a century. It reopened with ‘the splendid Golden Corinthian Saloon, and two new figures of the Duke of Sussex and Sir Walter Scott’. [3] Following the departure of Tussauds, their old premises at the Bazaar were briefly used in 1885–6 as the Baker Street Picture Galleries, for the sale of paintings on commission. They reopened in 1886 as a venue for hire called the Portman Rooms. Among the first activities were Miss Chreiman’s classes for the Hygiene and Remedial Physical Training of Girls. In 1889 refurbishment and redecoration was carried out by the famous Newman Street decorators Campbell, Smith and Campbell, under the joint supervision of the architects Sir Arthur Blomfield and J. S. Paul. It was a lavish transformation, involving mirrors, velvet, stained glass, embossed papers and anaglypta, stencilling and Classical sculpture, coloured in yellow, white, bronze, gold, indigo, cream and Pompeian red. The Great Room was remodelled as the Large Ballroom, with a new coved and moulded ceiling treatment, and other principal spaces were remodelled to provide a second ballroom and a supper room.

Madame Tussaud’s waxworks in the Great Room, probably 1880s (Westminster Archives)

The Portman Rooms became one of the best-known London venues for dances, concerts, charity bazaars, political, religious and social meetings of all sorts, including many events promoting women’s suffrage. An early form of cinema, the Anarithmascope, was exhibited there in 1896–7. But the place seems to have fallen on hard times after the death of the Boulnois brothers. In 1913 the main ballroom was declared structurally unsafe, and it was suggested by the authorities that the ‘inmates’ should be transferred to Marylebone workhouse. Repairs were carried out, and in 1916 the Portman Rooms were requisitioned as a military hospital and Royal Army Medical Corps barracks. After the war, Tussauds were keen to move back to their one-time premises, but found too many difficulties in meeting safety regulations and had to give up the idea. Instead, the Portman Rooms re-opened to the public in 1919 as the grand ballrooms and function rooms which they remained until the next war.

Over the years there were various temporary exhibitions. The big attraction of 1843 was the Glaciarium and Frozen Lake, a skating rink with painted Alpine scenery, employing a chemical ice-substitute. A ladies-only morning session was followed by general admission and after dark the lake was artistically lit – ‘the moon rises, stars glitter, and music enlivens the whole scene’. [4] It proved popular, and Prince Albert was among those who tried it out, before it was replaced by a bigger version set up elsewhere in 1844.

Carriage sales continued through the nineteenth century, and in the twentieth gave way to sales of motor-cars. In 1870 the Boulnois firm branched out into another venture, with specially built storage warehouses on the west side of the site in what is now Rodmarton Street. These were converted in 1922 into a social club for shopworkers, with its own dance floor, billiard rooms and restaurant.

Meanwhile, the furniture department grew into an important separate business following its acquisition in the 1840s by a Regent Street draper and upholsterer, Thomas Charles Druce. He died in 1864 but his family firm was eventually to take over the entire Bazaar site. Druce’s developed into a department store, though always specializing in furniture, took over the businesses of warehousing and sales from W. & E. Boulnois, and also branched out into undertaking and estate agency.

The name of Druce will be forever associated with the wild goose chase set off in the 1890s when T. C. Druce’s widow claimed that her husband had not died in 1864 but had been in reality the eccentric 5th Duke of Portland, who died in 1879, and therefore that her son was heir to the Portland estates. The duke (briefly in the Second Life Guards, though not until shortly after the regiment left King Street) was alleged to have come and gone in disguise through a secret passage – his London residence was not far away, in Cavendish Square. Physically, the Bazaar was a warren, organic in its development, with little exterior presence on account of its being corseted by the houses and shops along the street frontages of the nearly two-acre block. Possibly this gave credence to a sense of mystery and fuelled Mrs Druce’s fantasies of double identity. The passage, however, was merely a fire exit, not actually installed until after T. C. Druce’s death. The celebrated but preposterous Druce–Portland case was not resolved until Druce’s coffin was opened to reveal his well-preserved body in December 1907.

In December 1940 almost the entire premises burned out in an air raid. Further damage followed. For five successive Sunday mornings traffic was diverted so that the ruins could be safely brought down. Thereafter, Druce’s continued to operate from more than one Baker Street address but the business contracted, with the closure in the 1950s of the department store and auction rooms, and the name is now just that of the estate agency.

References

1. Morning Chronicle, 17 March 1826

2. The Standard, 8 June 1840

3. Morning Chronicle, 26 March 1835

4. Bristol Mercury, 17 June 1843

Close

Close