125 years of the Survey of London

By the Survey of London, on 6 September 2019

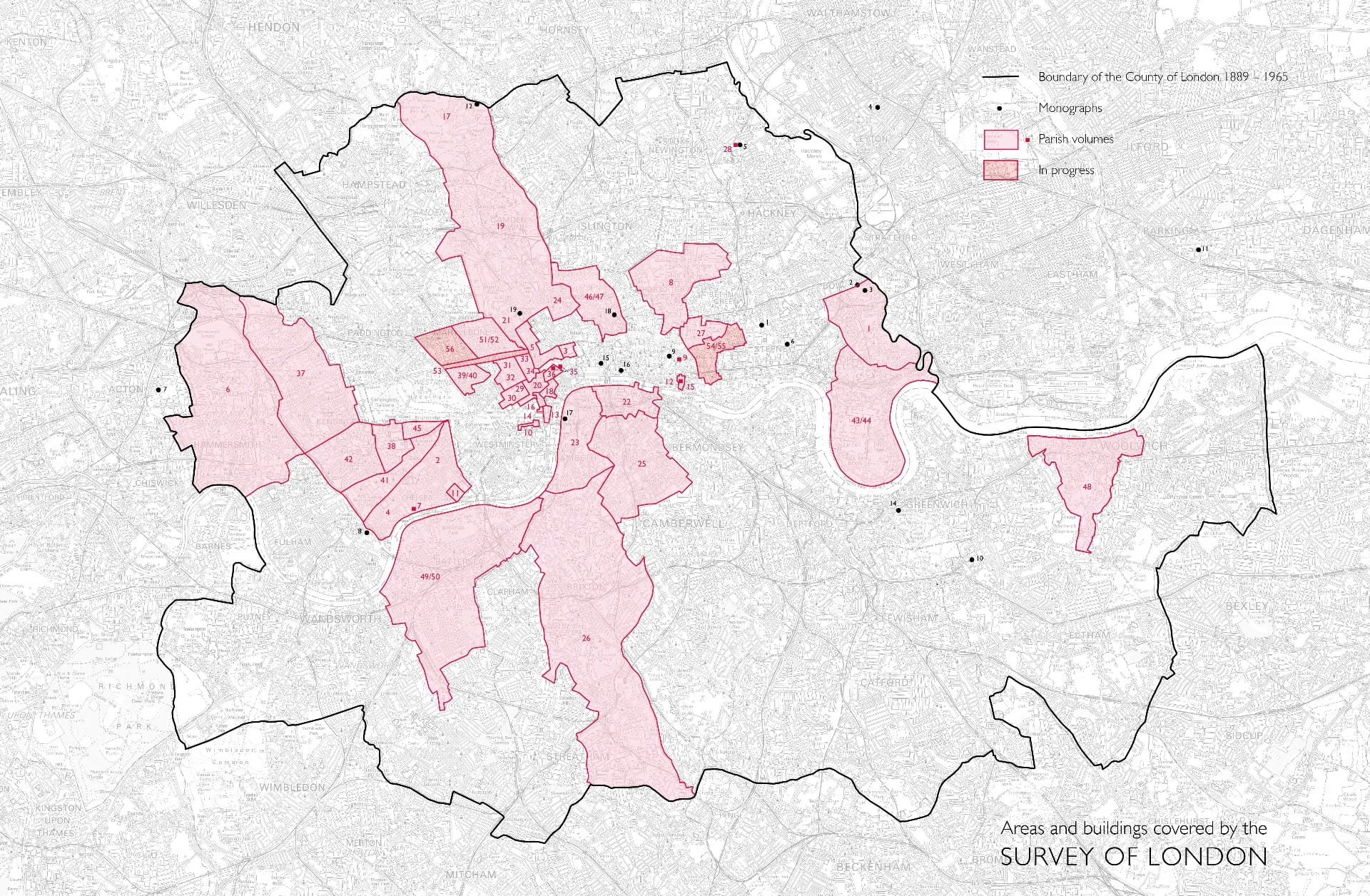

This year marks the 125th anniversary of the Survey of London, a venerable institution that produces architectural and topographical studies of districts of London. To mark that milestone this blog post traces the Survey’s remarkable history, from its origins as a recording project undertaken by a band of volunteers to its present-day work carried out from its current base at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London.

C. R. Ashbee, photographed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1900

The Survey traces its roots to the Arts and Crafts architect, designer and social thinker Charles Robert Ashbee, who established a Committee for the Survey of the Memorials of Greater London in 1894. Ashbee’s efforts to produce a ‘register’ or a list of buildings were prompted by the demolition of a Tudor hunting lodge in Bromley-by-Bow to make way for a Board School, which coincided with a growing sense of unease around the destruction of historic fabric in London. Members of the Committee decided to focus their work initially on the east side of London. Drawings, photographs and notes were produced to record buildings of interest and inform conservation. The first publication was a monograph on Trinity Almshouses in Mile End Road, which was threatened with demolition at the time. The resulting volume (published in 1896) interwove architectural history with social and cultural threads, contributing in no small part to a successful campaign for preservation of the almshouses.

Bird’s-eye view of Trinity Almshouses from Mile End Road, looking north. Illustration by Matt Garbutt

Two elderly sea-captains playing draughts. Illustration by Max Balfour

The Committee soon started to collaborate with the London County Council (LCC), which agreed to cover the cost of printing volumes relating to the more confined area under its jurisdiction. From this point onwards, the geographical remit of the Survey has been restricted to the area within the County of London as between 1889 and 1965. The LCC subsequently published the first volume in the main or ‘parish’ series, which focused on Bromley-by-Bow (1900). The project was infused with Ashbee’s social ideals, particularly his conviction that to mark down a record of historic buildings was an essential public good that would enhance the lives of Londoners: ‘We plead that the object of the work we have before us, is to make nobler and more humanly enjoyable the life of the great city whose existing record we seek to mark down; to preserve of it for her children and those yet to come whatever is best in her past or fairest in her present; to induce her municipalities to take the lead and to stimulate among her citizens that historic and social conscience which to all great communities is their most sacred possession.’

Progress report of the Committee printed in 1897, including a list of honorary members, who received a copy of the volumes in return for a subscription

Despite the early links with the capital’s governing body, the Survey was not formally associated with the LCC for some time. In 1907, after Ashbee’s relocation to Chipping Campden, management of the Committee passed to Philip Norman, Percy Lovell and Walter H. Godfrey. After protracted discussions, an agreement between the Committee and the LCC was finally reached in 1910. The Committee agreed to deposit its extensive collection of material with the LCC, in exchange for the Council bearing the cost of printing the volumes. This arrangement continued for more than forty years. Under the auspices of the LCC, the Survey shifted gradually from being a project led by amateurs and enthusiasts – ‘whose’, to borrow Ashbee’s words, ‘best work is done on Saturday afternoons and summer holidays’ – to one undertaken by professional historians. The LCC embarked on a study of the parish of St Giles-in-the-Fields and Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which coincided with its plans to form Kingsway and Aldwych and in the event contributed to the preservation of buildings. The production of the series was balanced between the LCC and the Committee, which published volumes alternately under a Joint Publishing Committee.

Pamphlet circulated to mark the publication of Eastbury Manor House (1917) the eleventh volume in the monograph series

The early volumes were consequently uneven in style and selective in scope, often focusing on the oldest or most high-status buildings in a parish. Each volume followed a similar format, comprising a map of the study area, an introduction, a register of buildings and a sequence of illustrations, including photographs and measured drawings. A separate series of monographs, focusing on single buildings and individual sites of particular interest, was published in parallel with the main ‘parish’ series.

Ida Darlington and Marie Draper, c.1950

After the completion of four volumes on St Pancras in 1952, the Survey Committee was disbanded. It was a decision reluctantly taken, brought about by a lack of ‘recruits for the heavy unpaid work which an earlier generation undertook with enthusiasm.’ [1] The editing work was at first taken on by Ida Darlington, who had started working on the Survey as a research assistant in 1926, but it proved impossible to balance with the considerable demands of her existing role as head of the record office and library at the LCC.

Francis Sheppard, the first General Editor of the Survey of London

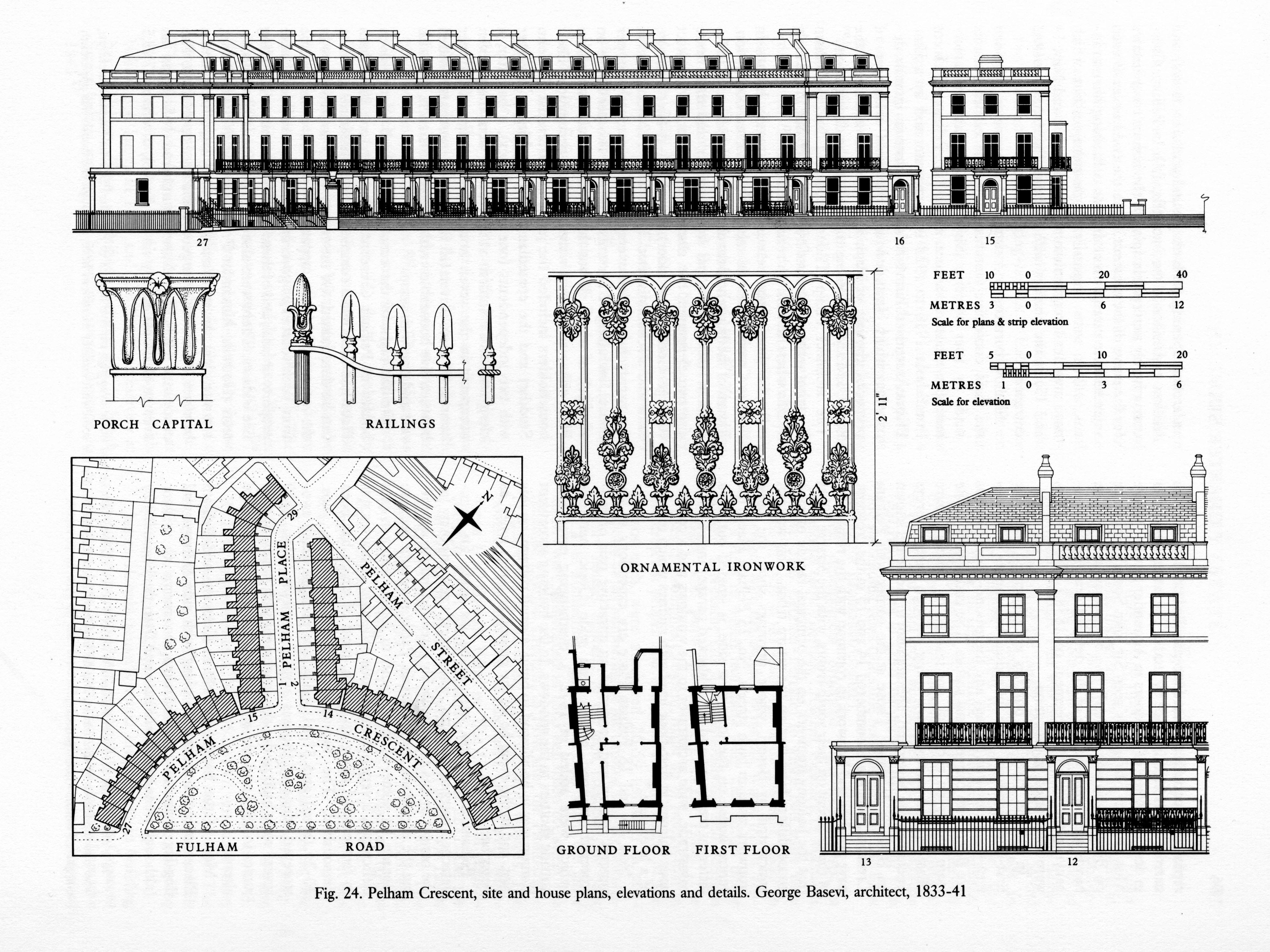

From 1954 the Survey was managed entirely by the LCC, which appointed a General Editor to lead a small team of full-time staff. The first General Editor was Francis Sheppard, who oversaw the production of the series until his retirement in 1983. During those twenty-nine years, Sheppard published sixteen volumes in the Survey’s main series and developed a unique and enduring formula for its work: a complete record of the built fabric of each study area, integrated with social and economic detail.

Bird’s-eye view of Covent Garden Market area. Drawn by F. A. Evans and T. P. O’Connor (Survey of London, Volume 36, Covent Garden, 1970)

Note to Francis Sheppard from John Betjeman, 1959

After the abolition of the LCC in 1965, the Survey transferred to the Greater London Council (GLC). In an interview with The Daily Telegraph in 1976, Sheppard described the approach to choosing study areas: ‘Basically we have to decide where surviving buildings are thickest on the ground and where they are most likely to be demolished most quickly, but of course we don’t only describe existing buildings. We also list those which have been destroyed.’ Sheppard concentrated the Survey’s investigations on the West End, where many Georgian streets were threatened with demolition. Research in Covent Garden resulted in the listing of many buildings and helped to alter proposals for drastic redevelopment.

Pelham Crescent, site and house plans, elevations and details. Drawn by John Sambrook (Survey of London, Volume 41, Brompton, 1983)

Following the dissolution of the GLC in 1986, the Survey became part of the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England, where work continued on volumes on County Hall (Monograph 17, 1991) and Poplar, Blackwall and the Isle of Dogs (Volumes 43 and 44, 1994). Studies were subsequently made of Knightsbridge (Volume 45, 2000), Clerkenwell (Volumes 46 and 47, 2008) and the Charterhouse (Monograph 18, 2010). In 1999 the Royal Commission merged with English Heritage. The team next moved its investigations south of the river to Woolwich (Volume 48, 2012) and Battersea (Volumes 49 and 50, 2013). The Survey remained under the purview of English Heritage until 2013, when it joined the Bartlett School of Architecture at University College London.

The Survey of London team in 2013, photographed in the year of the publication of the fiftieth volume in the series

The Survey continues to produce detailed topographical studies from its new home at the Bartlett, earning recognition for its scholarly rigour and pioneering approaches. In 2018, the Survey was honoured to receive the prestigious Colvin Prize from the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain for two volumes (Nos 51 and 52) covering south-east Marylebone (2017).

The Langham Hotel, Langham Place, drawn from measured survey by Helen Jones and Andy Crispe (Survey of London, Volume 52, South-East Marylebone, 2017)

All Saints’ Church, Margaret Street, view towards the east end (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave, published in Survey of London, Volume 52, South-East Marylebone, 2017)

John Lewis, detail of Oxford Street front at the corner with Old Cavendish Street in 2018 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

The Survey is continuing its work in Westminster with a volume covering Oxford Street (Vol. 53), which is set to be published in Spring 2020, and a volume on south-west Marylebone (Vol. 56). The current study of Whitechapel (Vols 54 and 55) has been supported by a major grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, which has funded the development of a public collaborative website to experiment with integrating memories, moving images and texts, illustrations and experiences by numerous others with the work of the Survey. Research has also commenced towards a monograph on UCL’s campus in Bloomsbury.

St George’s Lutheran Church and School, Alie Street, Whitechapel. Drawn by Helen Jones of the Survey of London

Map of the London Hospital and its surroundings in Whitechapel, showing the footprint of the main hospital building, specialised departments, and nurses’ homes. Redrawn by Helen Jones from Ordnance Survey maps of 1913 and 1948

The Survey’s detailed investigations do take time, and even after 125 years a good deal of the map remains untouched. As the architectural historian Sir John Summerson said, ‘The Survey will never be finished. If the time comes when a final “coverage” seems to be in sight it will be time to begin again. London changes. So does the writing of history. The Survey as the continuing illustrator and expositor of the fabric of London has a function with no imaginable term.’

[1] Walter H. Godfrey, lecture at the University of London, 5 January 1954

St George’s German Lutheran Church and Goodman’s Fields

By the Survey of London, on 9 August 2019

St George’s German Lutheran Church on Alie Street is located in an area known as Goodman’s Fields in Whitechapel. Though now associated with the recent Berkeley Homes development to the east of Leman Street, for many centuries ‘Goodman’s Fields’ extended much further west, all the way to Mansell Street. It was named after the Goodman family, who held much of the open pasture land regarded as the ‘fields’ in the late sixteenth century. A hundred years later, under the Leman family, the principal streets – Mansell, Leman, Prescot and Alie Streets, were laid out, and the first proper wave of building development took place.

Second and third waves of development saw these streets and others close to St George’s lined with a mixture of substantial mercantile houses, smaller house-workshops, and large factories. However, industries such as sugar refining and gun making increasingly characterised the area, and, by the middle of the nineteenth century, rows of densely occupied terraced houses were constructed on the last remaining open ground. After population dispersal and extensive bomb damage during the two world wars, Goodman’s Fields suffered a loss of identity and a period of decline, becoming home to many large speculatively built office blocks by the early 1990s. In 2019, the area is undergoing a further transformation, with only a limited proportion of the historical built environment remaining, increasingly overshadowed by tall blocks of flats.

The Survey has prepared a new exhibition centring on buildings local to St George’s German Lutheran Church in Goodman’s Fields. It will be displayed at St George’s on 21st and 22nd September, and thereafter migrate around other Whitechapel venues. This post presents a sample of the exhibition, exploring the history of this quickly changing area.

Alie Street elevation of St George’s German Lutheran Church and associated buildings, from an illustration by Dolfer, 1821. Redrawn by Helen Jones for the Survey of London

St George’s German Lutheran Church

St George’s German Lutheran Church is the oldest surviving German church in Britain. Since the eighteenth century, St George’s has been a haven for thousands of German Protestants seeking economic opportunity and religious asylum in the Whitechapel area. Sugar refining is interwoven with St George’s history, having served as a major economic driver for the German immigrant community. Dederich Beckmann (c.1702–66), a wealthy sugar refiner, was a key founding leader of the church and donated substantially towards its construction. The site of St George’s was purchased in 1762, with construction beginning soon after. Joel Johnson and Company served as builder, possibly also architect, and the chapel was consecrated on 19 May 1763. Before fitting out was complete, the building was enlarged at its north end in 1764–5. The church’s vestry was also built at this time.

The church’s external appearance does not demonstrate any clear German architectural connection, rather it is in keeping with other English Nonconformist chapels of the period. Composed of stock brick, its Alie Street façade is symmetrically arranged and features a central Venetian window flanked by identical doors. Centred above the window is a lunette, perhaps at one time glazed, that now reads ‘Deutsche Lutherische St Georgs Kirche Begründet. 1762’ (St George’s German Lutheran Church. Founded 1762). The church’s slate roofline was initially crowned by a bell turret, clock, and weathervane. This was dismantled in 1934 when rot and woodworm were discovered after several decades of deferred structural maintenance. A plain cross can now be found where there was formerly the clock’s face.

Alie Street elevation of St George’s. Photographed in 2017 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

Several sequences of repairs and restoration works resulted in replacement of all the original windows. Little else has been altered externally. However, the present juxtaposition between the simple church and towering neighbouring buildings reflects broader local shifts that have taken place in recent decades. Extensive restoration was undertaken in 2003–4, following the transfer of St George’s to the Historic Chapels Trust in 1999. In 2019, St George’s continues under the care of the Trust in partnership with the Friends of St George’s German Lutheran Church. Together they host talks, tours, concerts, and other public events to connect St George’s to the wider community.

Interior of St George’s, c.1930 (Courtesy of Friends of St George’s)

The arrangement of the sanctuary space reflects the evolutionary process of the church’s use, but also retains its original orientation, laid out in a typical Protestant fashion. Pews and galleries are centred around a main speaking platform, giving liturgical emphasis to preaching and the reading of scripture. This focus became a point of contention when the congregation’s first pastor, Dr Gustavus Anthony Wachsel (c.1735–99) incorporated hymn-singing and other musical performances into the more ‘pious’, word-focused liturgy, earning the chapel the critical nickname ‘St George’s Playhouse’. By 1802, the railed sanctuary had been made smaller, giving congregants closer proximity to the altar, and an organ had been installed. This was replaced by a larger instrument in 1885–6 resulting in the removal of upper galleries, which may have been made superfluous by declining attendances.

In the first few decades of the twentieth century, the St George’s community faced numerous difficulties under the strong and steady leadership of Pastor Georg Mätzold (1862–1930). During the First World War, anti-German sentiment was high, and many congregants returned to Germany or were interned. Despite these challenges, the congregation continued to meet, and following Mätzold’s death, the much-diminished community turned to reviving their religious home. This work included a reorganization of the chapel interior, in which a committee room was made under the south gallery. Dr Julius Rieger commemorated his predecessor by dedicating the room as the Mätzoldzimmer, as it is still known. During and after the Second World War, the congregation not only continued to meet but increased in size as new German refugees entered London’s East End. In the second half of the century, attendances declined. A plan for re-arranging the interior by the architect J. Antony Lewis in 1970 would have removed much of the intact joinery, including the pews and large portions of the galleries. This, however, never came to fruition, allowing the eighteenth-century interior joinery to remain intact. It is a significant survival.

Proposed interior reorganisation by J. Antony Lewis, 1970 (Courtesy of Friends of St George’s)

St George’s Schools

A burial ground east of St George’s church was gradually built over. By 1800, a substantial four-storey parsonage adjoined the church adjacent to which stood a modest clerk’s house, likely constructed when a single-storey school replaced stable and coach-house buildings further east (see the drawn elevation above).

St George’s church foundation included ‘German and English Schools’ from 1765, but an operational school was only formally established in 1805, when the parsonage and clerk’s house were given over for educational use. By 1808 a small school building had been erected, accommodating a mixed class of girls and boys aged seven to fourteen. Pastor Christian Schwabe, who served at St George’s from 1799 to 1843, was instrumental in all this and an experienced teacher. Schwabe moved to Stamford Hill where he established a school for distinguished German families, many of which, with other wealthy German merchants, some involved with sugar refining, supported the new Whitechapel school. Voluntary contributions enabled a proportion of less well-off children to attend on scholarships. The numbers of pupils increased rapidly, and girls were separated from boys after a decade with the girls’ classes moved to the parsonage. Other rooms in the parsonage were given over to a new infants’ school, established in the 1850s.

Watercolour of St George’s Infant School of 1859 (Courtesy of Friends of St George’s)

A two-storey infant school was completed in 1859, funded by W. H. Göschen, a banker who was the son of Goethe’s publisher. Held to be the first of its kind in the city, the school allowed mothers to go out to work during the daytime, ‘an urgent necessity amongst London’s growing German population’. By 1877, 283 children were registered at the infants’ school, and the intake of the junior schools had increased to the extent that the existing accommodation on Alie Street was unsuitable. The whole frontage east of the church was then redeveloped, with E. A. Gruning, himself an immigrant German, being the architect. The most significant benefactor was local sugar baker, James Duncan. The rebuilding was spurred on by the enthusiasm and energy of the Rev. Dr Louis Cappel, minister between 1843 and 1882.

St George’s German and English School. Photographed in 2017 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

The elementary school closed in 1917 when Pastor Mätzold was deported to Germany. The lower floors were soon used by tailoring businesses, and the upper storeys let out. By 1949 the infant school was disused. In 1983 St George’s converted the first floor into a student hostel/dormitory and retained the basement as a church hall. Both the schools were wholly converted into residential premises in the 1990s.

17 Leman Street

Opening in 1861, the German Mission Day School replaced an eighteenth-century tenement and family-run bakery. Designed by City architect Edward Ellis, the purpose-built school was one of a handful clustered around Buckle Street and the east end of Alie Street, primarily serving the large local German population. This school was supported by a group of German churches and funded through subscriptions from wealthy German individuals. Its initial aim was to educate the poor children of seamen, and it was in some ways a complement to St George’s Infants’ School. It was well attended, with enrolment reaching 150 within a few years of opening. However, by the end of the nineteenth century many German families had moved out of Whitechapel. This, coupled with the establishment of Board Schools following the Public Schools Act of 1868, led to the school’s closure in 1897 and the building being let out for commercial purposes.

Entrance to 17 Leman Street (now demolished). Photographed in 2007 by Danny McLaughlin

By 1903, the former Mission School was in use by the Jewish Working Girls’ Club (JWGC), which began in 1881 as a small sewing circle. It initially met in a house in Prescot Street and moved to the Gravel Lane Board School in Wapping in 1886. After its relocation to Leman Street, the JWGC purchased the freehold through the support of a Jewish-American philanthropist, Mrs Charles Henry, to serve as a goodwill gesture at a time of restricted US immigration policies. The building was lightly adapted for its new use by the architect M. E. Collins to include recreation rooms, a kitchen, scullery and library. The club was successful through the 1920s, with regular attendances of 160 for classes such as needlework, cooking, Hebrew and religion, singing and drill. Reliant on voluntary contributions from the local Jewish community for its operational expenses, the Club experienced periods of financial instability and closed at the beginning of the Second World War.

Jewish Working Girls’ Club. Reproduced from Living London, George R. Sims (ed.), 1902

Soon after the war’s outbreak, the War Office requisitioned the building for use as a hostel for black seamen from British colonies. Many West Africans and West Indians supported the British war effort by joining the merchant navy and serving in perilous situations at sea. Their arrival on British shores, however, posed difficulties. Those who found themselves in East London encountered underlying racism at the docks and were often turned away from other seamen’s hostels. As the Colonial Office hostel, this building provided a place for twelve men to stay for three weeks at a time, with shared spaces including a dining room, kitchen and common room. Despite the good intentions of providing camaraderie and support, those staying often struggled to find work and settle in the country, leading to criticism of the institution’s management. After much debate over the role of the Colonial Office in providing this support, the hostel’s ownership was transferred into private management in October 1949, in part facilitated by the London Council of Social Service. By 1959, the building was in use as a dress factory by H. Bellman & Sons Ltd. The former school was demolished in 2013, the site now contains a twenty-two storey aparthotel.

The Eastern Dispensary

The Eastern Dispensary was one of the oldest institutions of its kind in London. Founded in 1782 to provide free healthcare to poor local residents, the dispensary was first sited on Alie Street. It claimed an ‘on-call’ midwife, able to care for women in their homes, and a resident medical officer, alongside visiting surgeons and physicians of some standing. By the mid-nineteenth century, against the backdrop of a swollen local population, the old Alie Street premises were deemed no longer fit for purpose. Many London livery companies, local merchants and sugar bakers subscribed to the rebuilding project. The ‘new’ Eastern Dispensary opened at 19A Leman Street in February 1859 to designs by G. H. Simmonds, a local surveyor and the secretary of the dispensary who was also involved with the Royal Pavilion Theatre and the Davenant School. He deployed an Italianate palazzo style, but it is not clear that the original exterior design as seen in The Illustrated London News was wholly implemented.

The Eastern Dispensary in Leman Street. Reproduced from The Illustrated London News, 19 February 1859

The popularity of the dispensary remained high until the 1930s. It drew patients not only from Whitechapel, but from all around London and surrounding counties to visit clinics, many of which were held in the evenings to ensure patients did not lose income, nor employers man-power. Some alterations to the façade were made in 1929, and further repairs followed in 1936. By this time, attendances were dropping due to the improved general health of local people. The loss of population and staff during the war, as well as bomb damage to the building, precipitated the dispensary’s closure in 1940. Governors hoped to re-open it, but the establishment of the National Health Service in 1946 rendered the dispensary redundant. In 1944, the building was briefly occupied by the Jewish Hospitality Committee, who undertook substantial renovation and restoration, purposing the interior as a canteen and social club for the allied forces. Thereafter the lease was transferred to the Association for Jewish Youth. The building was sold in 1952, and then used for several decades by second-hand clothes merchants, S. Turner & Co.

The former Eastern Dispensary. Photographed by Derek Kendall in 2017 for the Survey of London

By 1980 the building was vacant and it suffered some neglect prior to listing in 1986. It was refurbished and insensitively adapted to use as a pub in 1997–8, with little or none of the original interior fittings remaining intact. It is only as a result of this refurbishment that the seven-bay Leman Street façade now does resemble exactly the scheme as published in 1859. Rustication extends across the lower storey, the first-floor windows are pedimented, and the roofline is articulated by a projecting cornice, above which sits an inscribed ‘Eastern Dispensary’ panel. The Dispensary Pub closed in mid-2019 and the building currently stands vacant once again.

The last jellied eel men in Whitechapel

By the Survey of London, on 12 July 2019

Jellied eels are a delicacy that divides opinion. The cold, viscous texture, and a colour that can only be described as grey, are not immediately suggestive of epicurean treats. But to many East Enders they are the taste of home. This is especially true if they now live a long, long way from Aldgate Pump. Mark Button, managing director of Barneys Seafood, the last jellied eel company in Whitechapel, knows this only too well. ‘We send them all over the country… We post them up to Scotland and Wales, a lot to the South coast, the Kent coast is still a very good area for jellied eels and even down to Devon and Cornwall.’ But sadly, though Mark plans to carry on jellying eels, from the end of September it won’t be in Whitechapel. Gentrification has caught up with the railway arches in Chamber Steet, in the south-west corner of Whitechapel, a stone’s throw from the Tower of London, that have housed Barneys for more than fifty years.

Mark Button, right, Managing Director of Barneys Seafood, outside the shop door at 55 Chamber Street, with his son Harry. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

Jellied eels are a cheap, traditional London dish going back to the eighteenth century. Eels were formerly plentiful in the Thames downriver towards the estuary, and the method of preparation served both to cook the eels and to preserve them. Though nowadays you are more likely to find them on a day out to the seaside at Southend or the south coast, both areas that buy Mark’s eels in large quantities, up until the 1970s jellied eels were readily available on market stalls and in pie and mash shops throughout east and south London. Only a few of these vendors now remain.

The most famous of jellied eel stalls in Whitechapel was Tubby Isaacs at Aldgate, at the south end of Petticoat Lane market. The original Tubby Isaac was Isaac Brenner, who opened his stall in Whitechapel in 1919, but emigrated to the United States in 1940.[1] Tubby Isaac’s or Isaacs, as the stall came generally to be known, was taken over by Soloman Gritzman – with Brenner’s departure Gritzman ‘became’ Tubby Isaacs.[2]

Solly Gritzman had a brother, Barney, who was in the same line of work and it is from Barney Gritzman that Barneys Seafood is descended. But, as with many East End stories, this was no tale of brotherly love. ‘There was a feud between the two brothers’, says Mark. ‘They had stalls opposite each other but they didn’t speak… they’d even spit at each other.’ This went on for more than twenty years.

Barneys Seafood, tucked under in railway arched a stone’s throw from Tower Bridge. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

Barney Gritzman had taken over the railway arches in Chamber Street as a lockup for the stall at Aldgate. At that time they really were railway arches, sitting under the junction of two different railways – the surviving line which had begun as the London and Blackwall, one of London’s earliest railways, leading to Fenchurch Street station, and the London and North Western Railway branch leading up to the Haydon Square goods depot, between Mansell Street and the Minories. That branch line closed in the late 1960s, when Barney’s shop and factory became a railway arch without a railway. This was the point at which Mark Button’s father, Eddie, took over from Barney Gritzman.

‘My Dad was one of fourteen children of a builder but decided he didn’t want to do that so he started to look around for other work. He started in a pie and mash shop, handling eels. He worked for Cooke’s pie shop in Stratford, and he then got a job at the old Billingsgate Market in Lower Thames Street working with eels, being a blocksman with fish, where they would prep fish for West End restaurants, and finally he bought Barney’s seafood stall at Aldgate in 1969.’

It was in the Chamber Street arches that Eddie Button developed the eel preparation and wholesaling business. The Gritzman brothers’ feud carried on even after Eddie Button took over Barneys, though, when, as Mark relates, Solly ‘Tubby Isaacs’ Gritzman ‘decided he didn’t want to do his own jellied eels any more and asked my father to do his eels as well, with the understanding that no one could know it was the same supplier supplying both Tubby Isaacs and Barneys’.

The cleaning room, at Barneys Seafood, 55 Chamber Street, the first stop fot the shipments of eels. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

Mark joined the firm in 1983, when he was 18, and despite the enormous demographic and culinary changes in East London in the past thirty-five years, has sustained and developed the business. ‘When I first came here we did ninety per cent jellied eels and ten per cent other shellfish … now we possibly do forty per cent jellied eels and sixty per cent other shellfish, but that forty per cent is still a large percentage of the eels industry for the south of England.’

A bucket of cleaned eels awaiting preparation. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

The processes that go on in the arches have not changed much over time. In the summer months shipments of wild eels are flown in overnight from Lough Neagh in Northern Ireland, arriving fresh for processing at Chamber Street in the early hours of the morning. In the winter the eels come in container lorries, once a week or once a fortnight, from eel farms in the Netherlands.

The eel preparation room at Barneys Seafood, 55 Chamber Street. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

Ginger and Simon gutting and cutting eels in the preparation room at Barneys. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

Ginger guts the eels before they are chopped into bite-size pieces prior to boiling. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

‘The eels are then cleaned and gutted, as one process, then they’re cut in to mouth-size pieces, then it’s all washed and then the raw material is cooked in boiling water.’

Eels chopped into pieces at Barneys Seafood before they go to the boiling room. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

Vats of boiling water, salt, gelatine, parsley and a blend of spices await the chopped eels in the boiling room at 55 Chamber Street. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

‘We add some salt and some spices just to take off any earthiness the wild eels might have, and because of the volumes we’re cooking we have to use a gelatine-based product to set the eels in. It’s a boiling liquid that then gets put in to a fridge overnight and the following day they are set as jellied eels.’

Chopped eels bubbling away in steel vats in the eel-boiling room at Barneys Seafood. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

Portioned jellied eels and liquor. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

The stall at Aldgate closed about six years ago. ‘With the red routes, no parking, double yellow lines, no taxi drivers allowed to stop, changing it all back to a two-way system from one way, the Congestion Charge, all these things put people off coming in to certain areas so it slowly killed the trade.’ But as one door closed another opened – literally. ‘When I first came here, we’d walk in in the morning and we used to close the door behind us, because there was so much work going on in the factory, my father didn’t encourage anyone off the street to come in. We were so busy no one had time to go and serve anybody. It’s only possibly been in the last ten or twelve years, since my father hasn’t been around, that we’re not doing as much work. So you open the doors, you put some freezer display cabinets in, people can come in and see what you do.’

‘We open the doors about 4.30 am and we’re here most days till about 1.30 in the afternoon. We’ve had to develop with the times … it’s about thirty per cent of the business I think now, people that walk in off the street. We supply cool bags and we’ve got a good little following, whether it’s people visiting for the day, students staying here, people sailing their boats into St Katharine’s Dock … we get everyone coming here. And you don’t know who they are till you start talking and … you know they’ve been sailing for six months and they come back here every year or so, and they come and find us again. And it’s retired people from America, all walks of life, you know, whether they’re scraping together a few pennies to buy something or they’re multimillionaires who just love a bit of jellied eels and seafood.’

Charles ‘Frank’ Mathews at the shop counter. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

The changing demography of the area around Chamber Street has been a boon to Barneys. ‘This was already a busy area, most of the time, but at weekends we’ve got more Europeans moving in, Leman Street has got a lot of Chinese and Asian students coming in from the Far East. It creates a different dynamic in the area, there’s the bars and restaurants, there are City people during the week and a lot of students at weekends, but they also like fresh fish and live produce, so we’ve got busier in our local trade over the last two to three years.’

There is a slightly bitter irony to this, of course. Last year Mark had a bit of a shock. ‘We got a letter from Network Rail, our landlord, saying the site had been sold. After fifty years of paying our rent on time, every time …’ In January 2019 the new owners, the developers Marldon, told Mark that Barneys would have to leave at the end of September. Mark is philosophical: ‘Well, they are developers. I think they’ve got an apart-hotel planned for the site.’

‘We’re looking at a few options at the moment.’ They may move in to Billingsgate Market, but that may itself soon be on the move for the same reason as Barneys. ‘In 1982 the fish market moved from Lower Thames Street to Canary Wharf which was the great move at the time, with readymade car parks and readymade cold stores, and it was hi-tech at the time. It’s not hi-tech today and the land values of Canary Wharf have outstripped the usage of a fish market which only trades from 3am until 9am.’ The market owner, the Corporation of London, has been contemplating moving all the old produce markets – the fruit and veg at Leyton, fish at Canary Wharf and, oldest of all, meat at Smithfield to a single site at Barking. ‘With the prospect of moving to Barking, with the new market, we’ll see what that brings with a multicultural type of market. There’s still a call for traditional shellfish. The jellied eel side of the business is declining but with trends changing and different types of people moving in to the area, people are willing to try these things again.’

So he is not downhearted. ‘You know, I could have panicked, shut up the shop and said “That’s it, had enough, going to do something else.” But because I came here at the age of 18 and apart from the 3am alarm going off most mornings … I’m fortunate my son’s now in the business, he’s 21, he wants to carry on doing it, he enjoys it, in some sad way as we all do. Once it’s in the blood I think it’s always there.’

Mark Button reflected in the frontage of Barneys Seafood, 55 Chamber Street. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

Mark Button was talking to Aileen Reid from the Survey of London at 55 Chamber Street on 26 June 2019.

Barneys Seafood will be at 55 Chamber Street, London E1 8BL till the end of September 2019: https://www.barneys-seafood.co.uk/

Solly Gritzman can be seen at his Tubby Isaacs stall, talking about Petticoat Lane market, in a BBC documentary from 1968, about four minutes in on the timer: https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p00t3mkz/one-pair-of-eyes-georgia-brown-who-are-the-cockneys-now

References

[1] Ancestry.co.uk: Daily Mail, 2 Sept 1926, p. 3

[2] The People, 17 March 1974, p. 2

The Baker Street Bazaar

By the Survey of London, on 14 June 2019

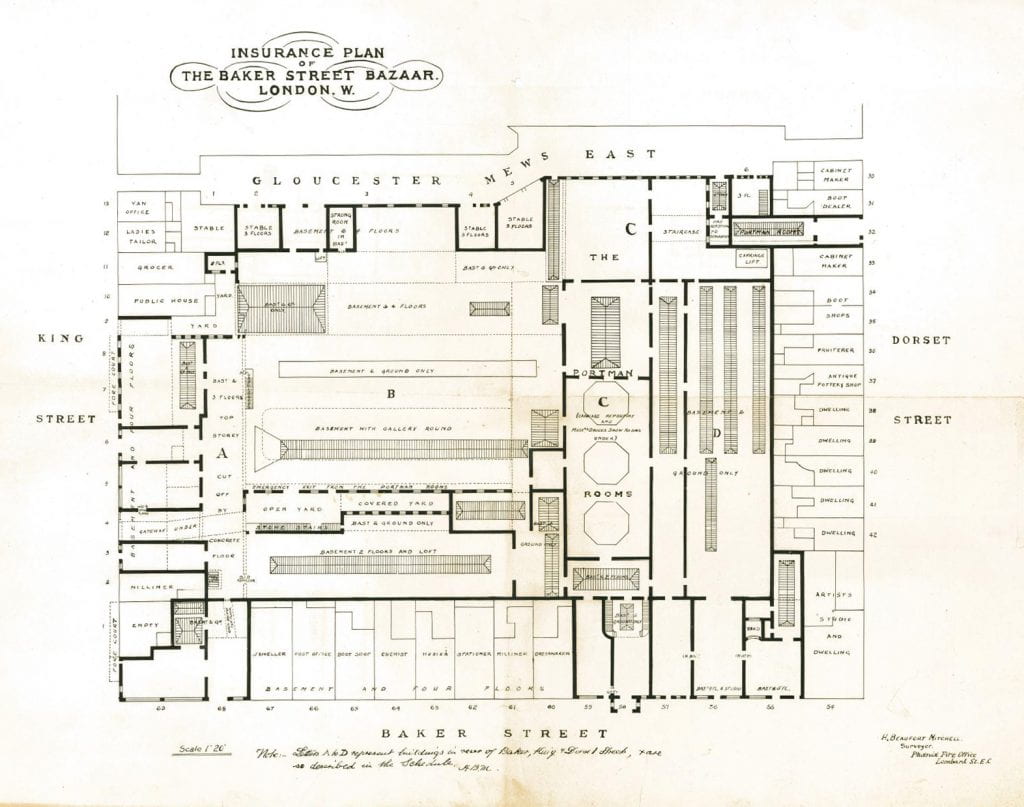

The Baker Street Bazaar was a group of buildings hidden behind houses and shops on the west side of Baker Street, between Blandford Street and Dorset Street. It was a famous place in Victorian times and well into the twentieth century, but the name was going out of use before the Second World War and what now seem to have been the great days of the establishment were by then long over. Burned out in the Blitz, the Bazaar was demolished in 1941 and its site became an American military car-park. In the 1950s it was redeveloped with the head offices of Marks & Spencer, coincidentally the pioneers of Penny Bazaars half a century earlier. Marks & Spencer moved there in 1957 from scattered offices, including those across the road at 82 Baker Street, where the company had been for many years. This was a time when important sites in Baker Street and elsewhere in this part of the West End were being redeveloped with corporate headquarters. Marks & Spencer’s were the biggest, and there was space for part to be let at first to another corporation, Metal Box, for its own offices. The buildings, known until Marks & Spencer’s departure in 2004 as Michael House, are still there but hardly recognizable following enlargement and remodelling by Make Architects in 2005–8, as 55 Baker Street.

In their origins, the blitzed buildings were neither a bazaar nor even in Baker Street. When the district was first laid out in streets, two of the main developers were Abraham Adams, originally a carpenter, and Thomas Elkins, a bricklayer. In 1771 they entered into agreement with the landowner Henry Portman for one particularly large site, with a plan involving a market square on the east side of Baker Street. Ten years later, the market having failed to appear, most of the ground had to be handed back to Portman. But a certain amount of work had been done round about, including one development still under construction. This was a barracks for the Second Troop of Horse Guards, one of several cavalry barracks called into being by the Napoleonic wars and conveniently close to Hyde Park. It seems that in the end Adams and Elkins had to give up the barracks too, for in 1791 Portman leased it to George and John Elwes, sons of the financier and legendary miser John Elwes, who were able to relet it to the government on lucrative terms. By that time, the occupying troop had been reformed as the Second Regiment of Life Guards, with men of lower social background replacing the previous complement of ‘gentlemen troopers’.

Quadrangular in layout, with a central parade ground and a riding house at the north end, the barracks was entered by passageways from the street on the south side, then King Street and only redesignated as part of Blandford Street in 1937.

The Horse Bazaar (Westminster Archives)

In 1821 King Street Barracks was replaced by a new barracks in Regent’s Park, and in 1822 reopened as the Horse Bazaar, the latest venture by the businessman and politician John Maberly. He had managed to get the premises at half the rent the government had paid, but was pouring money into the place. Maberly’s was a coachmaking and leather-dressing family, and he had married the daughter of William Leader, the Marylebone-based coachmaker to the Prince of Wales. With a fortune inherited from Leader, he plunged into manufacturing, contracting and finance, setting up banks and a soapworks, acquiring textile mills and supplying the army with uniforms. As an MP from 1816, for Rye and then Abingdon, he was a vociferous advocate of tax reform. At Shirley House, his seat near Croydon, he maintained racing stables. Maberly’s businesses were largely sound enterprises, but he became heavily involved in stock-market speculations and risky overseas loans. In 1832 his bank John Maberly & Co. suspended payments, and within weeks he was bankrupt. Only a fraction of his debts was ever paid off. He died abroad in obscurity some time later, but his son William Leader Maberly was able to pursue a successful career in the army and civil service, running the Post Office before Rowland Hill took over and living near his father’s Bazaar, in Gloucester Place.

At first the Bazaar was just for sales of horses on commission, but soon the business expanded, as carriage sales were introduced, advances were made on horses and carriages brought for sale, and harness and saddlery was sold. When it opened, it was described simply as comprising 300–400 stalls, with a large riding house and high-walled exercise ground – much as it must have been as a barracks. But subsequently it is clear that a great deal was spent. Accounts vary, but it was in the tens of thousands of pounds. There were light and spacious galleries capable of displaying 500-plus carriages, and the auction room itself was a top-lit hall with an elegant viewing gallery. Most expensive, no doubt, was the vast and lavishly decorated ‘Subscription Club’ room built over the riding house. This was once thought to have been the former officers’ mess, but it was too grand even for a guards’ regiment. It proved too grand even for the Subscription Club.

Although the word bazaar had been in use from the start, it was only with the opening of the ‘New Bazaar’ in 1826 that the establishment took on the character of a general retail market, aimed at the most fashionable and affluent shoppers. Encouraged by sales of tack, Maberly launched this fresh development based on John Trotter’s Soho Bazaar. Applications for stalls were sought from independent traders, and provision was made for the sale of furniture, pictures and other articles on commission, on which, as with carriages, advances were offered. A vast range of goods was promised, ranging from watches and jewellery to perfumery and toys. The furniture department was at the King Street end, while dozens of stalls comprising the Ladies’ or Fancy Bazaar occupied the gallery floor of the long eastern range. A house in Baker Street was acquired to form the entrance, and so the site in due course acquired its memorably alliterative name. At the north end the former Subscription Club room, renamed the Great Room, was fitted up with more stalls. Ante-rooms included one displaying glassware, one for music, another serving as a dressing room for ladies buying millinery. Refreshment rooms, reading rooms and private subscription rooms completed the ambience of leisure and luxury, while the female stallholders had ‘a more than ordinary share of youth and beauty’. According to an old story, Thackeray based Becky Sharp on Tizzie Reeves, an adventuress whose mother was one of these girls. ‘When these alterations are completed,’ it was claimed, ‘there will be assembled, under one roof, the most extensive collection of the luxuries, necessaries, or conveniences of life, probably to be met with in Europe; presenting the nearest approach we have yet seen to that Eastern market, from which it has taken its title’. [1]

The auction room at the Horse Bazaar (Westminster Archives)

With Maberly’s bankruptcy, the Bazaar was bought by the auctioneer Matthew Clement Allen, proprietor of Aldridge’s Repository, the horse and carriage mart in St Martin’s Lane. Allen’s brother-in-law William Boulnois, a City wine merchant, became involved, and in time took over parts of the premises, including the carriage and furniture departments. Horse sales were transferred to Aldridge’s in 1838, after which Boulnois had the whole Bazaar to himself.

Born to a French emigré family, Boulnois became squire of Gestingthorpe in Essex, where he died in 1862. Thereafter the Bazaar was run in partnership by two of his sons, William Allen Boulnois, architect and surveyor, and Edmund, who became a prominent figure in Marylebone as a businessman and in many public roles, including JP, Guardian of the Poor, LCC member and Conservative MP. Percy Boulnois, another brother, became the borough engineer of Portsmouth and a close friend of Arthur Conan Doyle. As Doyle’s biographer Andrew Lycett suggests, although the Bazaar never figures in the Sherlock Holmes stories, the Boulnois connection may have prompted the choice of Baker Street as Holmes’s address.

In 1840 William Boulnois announced the opening of an ironwork department, grandly called the Panklibanon. Manufactories on site were to permit the undertaking of contracts ‘of any magnitude’. [2] Unfortunately, all this was in breach of a covenant in the head lease against noxious trades. The new forges had to be dismantled and the manufacturing side of the business abandoned. Consequently the Panklibanon was reduced to showrooms only, with a range of goods from stoves and baths down to pans and tea trays. It passed through a succession of proprietors, before being taken over as the lighting and glassware showrooms of Apsley Pellatt.

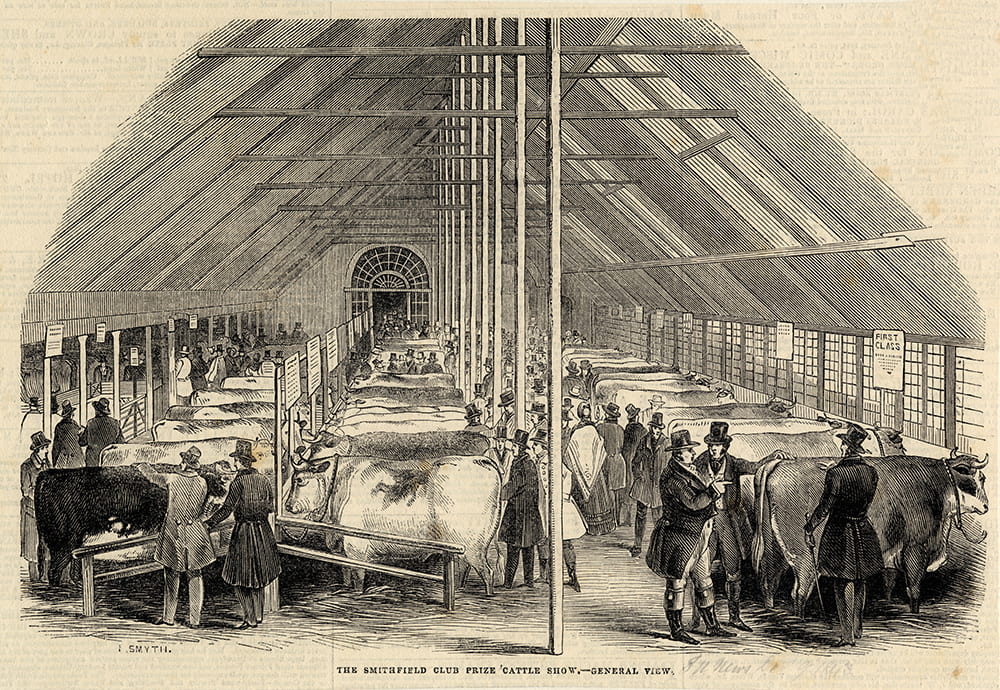

The Bazaar’s use for exhibitions went back at least to 1827, when George Pocock’s experimental kite-powered carriage, the Charvolant, was put on display. After horse sales were given up it became an important venue. The Smithfield Club, founded in 1798 under the Duke of Bedford’s presidency to improve livestock standards, held its annual show there from 1839. Boosted by the development of the railways, which enabled animals to be brought from afar, this was a pre-Christmas extravaganza of grotesquely overfed cattle, sheep and pigs combined with displays of the latest advances in farm equipment, and it was enormously popular and prestigious.

Smithfield Club cattle show in 1843 (Westminster Archives)

At first it was makeshift, with a temporary canvas roof and the ground so filthy that ladies in their long skirts were unable to attend. Later, improvements were made including a permanent iron-framed roof built to W. A. Boulnois’s design. Prince Albert was a regular exhibitor, and he and Queen Victoria visited on several occasions; red sand was put down in the show-yard. But the show outgrew the Bazaar, and from 1862 was held at the new Royal Agricultural Hall in Islington.

More important even than the Smithfield show was the waxworks exhibition of Madame Tussaud and Sons, which moved in 1835 from the Royal London Bazaar in Gray’s Inn Lane to the Great Room at Baker Street, where it would remain for half a century. It reopened with ‘the splendid Golden Corinthian Saloon, and two new figures of the Duke of Sussex and Sir Walter Scott’. [3] Following the departure of Tussauds, their old premises at the Bazaar were briefly used in 1885–6 as the Baker Street Picture Galleries, for the sale of paintings on commission. They reopened in 1886 as a venue for hire called the Portman Rooms. Among the first activities were Miss Chreiman’s classes for the Hygiene and Remedial Physical Training of Girls. In 1889 refurbishment and redecoration was carried out by the famous Newman Street decorators Campbell, Smith and Campbell, under the joint supervision of the architects Sir Arthur Blomfield and J. S. Paul. It was a lavish transformation, involving mirrors, velvet, stained glass, embossed papers and anaglypta, stencilling and Classical sculpture, coloured in yellow, white, bronze, gold, indigo, cream and Pompeian red. The Great Room was remodelled as the Large Ballroom, with a new coved and moulded ceiling treatment, and other principal spaces were remodelled to provide a second ballroom and a supper room.

Madame Tussaud’s waxworks in the Great Room, probably 1880s (Westminster Archives)

The Portman Rooms became one of the best-known London venues for dances, concerts, charity bazaars, political, religious and social meetings of all sorts, including many events promoting women’s suffrage. An early form of cinema, the Anarithmascope, was exhibited there in 1896–7. But the place seems to have fallen on hard times after the death of the Boulnois brothers. In 1913 the main ballroom was declared structurally unsafe, and it was suggested by the authorities that the ‘inmates’ should be transferred to Marylebone workhouse. Repairs were carried out, and in 1916 the Portman Rooms were requisitioned as a military hospital and Royal Army Medical Corps barracks. After the war, Tussauds were keen to move back to their one-time premises, but found too many difficulties in meeting safety regulations and had to give up the idea. Instead, the Portman Rooms re-opened to the public in 1919 as the grand ballrooms and function rooms which they remained until the next war.

Over the years there were various temporary exhibitions. The big attraction of 1843 was the Glaciarium and Frozen Lake, a skating rink with painted Alpine scenery, employing a chemical ice-substitute. A ladies-only morning session was followed by general admission and after dark the lake was artistically lit – ‘the moon rises, stars glitter, and music enlivens the whole scene’. [4] It proved popular, and Prince Albert was among those who tried it out, before it was replaced by a bigger version set up elsewhere in 1844.

Carriage sales continued through the nineteenth century, and in the twentieth gave way to sales of motor-cars. In 1870 the Boulnois firm branched out into another venture, with specially built storage warehouses on the west side of the site in what is now Rodmarton Street. These were converted in 1922 into a social club for shopworkers, with its own dance floor, billiard rooms and restaurant.

Meanwhile, the furniture department grew into an important separate business following its acquisition in the 1840s by a Regent Street draper and upholsterer, Thomas Charles Druce. He died in 1864 but his family firm was eventually to take over the entire Bazaar site. Druce’s developed into a department store, though always specializing in furniture, took over the businesses of warehousing and sales from W. & E. Boulnois, and also branched out into undertaking and estate agency.

The name of Druce will be forever associated with the wild goose chase set off in the 1890s when T. C. Druce’s widow claimed that her husband had not died in 1864 but had been in reality the eccentric 5th Duke of Portland, who died in 1879, and therefore that her son was heir to the Portland estates. The duke (briefly in the Second Life Guards, though not until shortly after the regiment left King Street) was alleged to have come and gone in disguise through a secret passage – his London residence was not far away, in Cavendish Square. Physically, the Bazaar was a warren, organic in its development, with little exterior presence on account of its being corseted by the houses and shops along the street frontages of the nearly two-acre block. Possibly this gave credence to a sense of mystery and fuelled Mrs Druce’s fantasies of double identity. The passage, however, was merely a fire exit, not actually installed until after T. C. Druce’s death. The celebrated but preposterous Druce–Portland case was not resolved until Druce’s coffin was opened to reveal his well-preserved body in December 1907.

In December 1940 almost the entire premises burned out in an air raid. Further damage followed. For five successive Sunday mornings traffic was diverted so that the ruins could be safely brought down. Thereafter, Druce’s continued to operate from more than one Baker Street address but the business contracted, with the closure in the 1950s of the department store and auction rooms, and the name is now just that of the estate agency.

References

1. Morning Chronicle, 17 March 1826

2. The Standard, 8 June 1840

3. Morning Chronicle, 26 March 1835

4. Bristol Mercury, 17 June 1843

Marks & Spencer (Pantheon store), 169–173 Oxford Street

By the Survey of London, on 17 May 2019

The site of the celebrated Pantheon (1772–1937), fronting Oxford Street and carrying through to Poland Street at the side and Great Marlborough Street at the back, is occupied today by the best-known London outlet of the Marks & Spencer chain, familiar for its distinctive polished black-granite frontispiece. The Pantheon was a place of public entertainment (originally with a spectacular domed interior) from its opening in 1772 to 1814, and afterwards the site of a bazaar and W. & A. Gilbey, wine and spirit merchants. The site was sold to Marks & Spencer Ltd in 1937. The store was constructed in 1938 by Bovis Ltd to designs prepared by W. A. Lewis & Partners in collaboration with Robert Lutyens (the son of Edwin Lutyens). It originally covered just the Oxford Street frontage of the Pantheon site, numbered 173 after 1880, together with the premises behind, but was extended eastwards in 1962–3 to take in the sites of Nos 169–171.

The front of the Pantheon branch in 2018 (© Historic England, Chris Redgrave)

Marks & Spencer Ltd opened their first West End branch at Orchard House, 454–464 Oxford Street near Marble Arch, in 1930. The decision to establish a larger store in the West End confirmed the success of the earlier enterprise and the energetic pace of the firm’s expansion. In 1916, Simon Marks took the helm of the company co-founded by his father and set about improving the business to fend off competitors such as Woolworth. Marks travelled to the United States in 1924 to study retail practices in chain stores, and returned with an insight into ‘the value of more imposing, commodious premises’, modernised administration and counter footage. [1] The public flotation of the company in 1926 generated funds for the construction of new stores. By the beginning of the Second World War, the company had built or rebuilt 218 shops and extended approximately 200 more. The Pantheon store was set apart from its contemporaries by its size, sophistication and superior location. One of its architects later recalled that it was ‘the store to outstore all stores, and the amounts involved in the acquisition of the site and the building were, by comparison with the stores which had already been erected, quite astronomical’. [2]

The task of designing this prominent store was entrusted to Lewis & Partners (later Lewis & Hickey), the architectural firm largely responsible for work in the south of England for Marks & Spencer. The building process was overseen by Ernest E. Shrewsbury, the head of its building department. Lewis & Partners also worked in collaboration with Robert Lutyens, who was appointed consultant architect to the company in 1934. He devised a standardised system for the street elevations of stores, which were faced with square artificial-stone tiles based on a ten-inch module to ensure uniformity and coherence. This inventive approach was applied to frontages of any size, including extensions. The application of polished black granite to the Pantheon and Leeds stores signalled their prestige and imitated the glamour of West End blocks such as the National Radiator Building (Ideal House) in Great Marlborough Street, Drages in Oxford Street, and the Odeon Cinema in Leicester Square. [3]

The Pantheon store, photographed in 1938 (The M&S Company Archive, P2/87/195)

The original store occupied the full site of the former Pantheon, reaching south to Great Marlborough Street and east to Poland Street. Lewis & Partners had produced plans for a three-storey north range fronting Oxford Street in 1936, but these were supplanted by a more ambitious scheme with a showy arcade. A four-storey block faced with shiny black granite was devised for the north front. The sleek façade was composed of five bays, with square first-floor windows set among chequer-work panels and three embrasures above containing tall Crittall windows and flat paterae. A plain parapet contained green neon lettering. The ground floor incorporated an arcaded shopfront executed by Holttum & Green of Holloway. This was lined with Bianca del Mare marble and furnished with gilded bronze display cases, including a central freestanding showcase. Two-storey ranges facing Great Marlborough Street and Poland Street were more modest in scale and quality of materials, being faced with glazed terracotta tiles. The east frontage initially comprised 39 and 41 Poland Street, its regularity interrupted by a pre-existing front at No. 40. The remainder of the site was occupied by a single-storey range which provided nearly 22,000 square feet of retail space. [4]

After the Pantheon branch opened in October 1938, an article in a trade magazine remarked that it was ‘designed and equipped on lavish lines’, incorporating features more commonly found in department stores. [5] The ground floor was devoted to sales, with approximately 2,200 feet of counter displays, garment rails and wall racks in an open-plan arrangement. The main retail departments were food, clothing, millinery, footwear and household goods. Extravagant decorative finishes included walnut counters and wall panelling, coffered ceilings and oak block floors laid in a basket weave pattern. Specialist technology in the store included a clock with a signalling system for managerial staff and pillars capped by aluminium light reflectors and grilles for heating and ventilation. A café at the back of the shop adopted a bold, streamlined style based on Wanamaker’s luncheonette in Philadelphia, with curved bars encircled by tall fixed stools with red-leather upholstery. A ladies’ writing and rest room was located on the first floor, with an adjoining lavatory and attendants’ office. The store also provided amenities for the welfare and training of nearly 300 employees, who included an interpreter for seven languages. The upper floors of the north range contained offices, a training room, comfortably arrayed rest rooms, and a canteen serving meals at low prices. The basement contained stock rooms with air-conditioned stores for foodstuffs and a loading bay in Great Marlborough Street.

The Pantheon store, photographed in July 1951 after its extension eastwards into 169–171 Oxford Street (The M&S Company Archive, P2/87/195)

In 1951 Marks & Spencer Ltd expanded eastwards into the basement and ground floor of 169–171 Oxford Street. This six-storey speculative block had been built in 1934 by James Carmichael Ltd to designs by Morris de Metz, replacing Vanoni’s restaurant and a shop. It had been mainly occupied from 1935 by Associated Talking Pictures Ltd, for whom the cinema architect George Coles made alterations, but the shop below had been in separate occupation. By this time, Marks & Spencer Ltd had expanded its catering provision for customers with tea and sandwich bars, ice cream counters, and a large self-service cafeteria with seating for 260 people. These additions probably compensated for the shortage of clothing during rationing. After the acquisition of the adjoining property, openings in the party wall were formed to extend the ground-floor shopping area and the basement stock rooms. Additional shopping space was formed by clearing the arcade shopfronts at both premises, restricting the main entrances to narrow lobbies flanked by display cases.

Sales at Marks & Spencer, Oxford Street Pantheon branch, in the early 1960s. Stocking counter in the foreground (Historic England Archive)

The eastern extension at Nos 169–171 was rebuilt in 1962–3 to secure a continuous street front for the enlarged store. The black-granite façade of the original store was extended by four bays, creating a symmetrical and uniform composition that attested to the adaptability of Lutyens’s modular system. A new shopfront had two recessed public entrances flanked by display cases, which admitted customers into an extensive and open-plan shop. The east front was also extended southwards to include 42–43 Poland Street. In the 1970s, a series of extensions tripled the area devoted to retail space. Lewis & Hickey oversaw a first-floor extension and the rebuilding of the rear of the store in 1971–2. A substantial five-storey range fronting Great Marlborough Street was constructed with irregular fenestration, grey-slate cladding interspersed with raised brown-brick panels, and a steep mansard roof. Public staircases, lifts and escalators on the ground floor ascended to a first-floor sales floor, with an adjoining stock room in the north range. A basement sales floor opened in 1978, increasing the retail space to 93,100 square feet arranged over three main floors. Around this time, the east front in Poland Street was rebuilt on an extended footprint to similar designs prepared by Lewis & Hickey, with a brown-brick and grey-slate elevation. The addition of a second-floor sales area followed. Successive refurbishments of the interior have left no original features behind the black-granite front.

The Pantheon store, photographed in March 1963 during construction works to extend the black-granite façade (The M&S Company Archive, P2/87/195)

References

1. Israel Sieff, Memoirs, 1970, pp. 141–60.

2. Patrick Hickey, cited by Asa Briggs, Marks & Spencer, 1884–1984, 1984, p. 47.

3. Lewis & Hickey, Sixty-Two Years Association with Marks & Spencer, 1984: Kathryn Morrison, English Shops and Shopping, 2003, p. 230.

4. Neil Burton, ‘Robert Lutyens and Marks & Spencer’, Thirties Society Journal, no. 5, 1985, pp. 8–17.

5. The Chain and Multiple Store, 22 October 1938.

Wombat’s City Hostel, formerly the Sailors’ Home

By the Survey of London, on 19 April 2019

This hostel on Dock Street sustains an institutional use that has its origins in the 1830s when the establishment opened as the Sailors’ Home, a reflection of the dependence of the southern parts of Whitechapel on maritime life. It is a large complex that extends back to Ensign Street (formerly Well Street), its original front.

Wombat’s City Hostel, 7 Dock Street, London E1. View from the west in 2017. Photograph by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

The Sailors’ Home, also known at first as the Brunswick Maritime Establishment, was built in 1830–5 with Philip Hardwick as its architect. Enlarged to Dock Street in 1863–5, substantially altered in 1911–12, rebuilt on the Dock Street side in 1954–7, adapted to be a hostel for the homeless in 1976–8, and again converted to be a youth hostel in 2012–14, this has been, mutatis mutandis, a major local presence for nearly two centuries, all the while used as a hostel. As the first purpose-built short-stay hostel for sailors anywhere, it represented in its original form the invention of a building type, the Royal Hospital for Seamen in Greenwich notwithstanding. It was to have seminal influence on the development of lodging-house architecture.

The story starts with a catastrophe, the collapse of the Royal Brunswick Theatre just days after its opening in February 1828. Thirteen people died and Hardwick, the architect at the neighbouring and then building St Katharine’s Docks, was the first on the scene of the disaster to take responsibility for the rescue operation. Of the theatre, all that survives is on the Ensign Street pavement, a row of (listed) cast-iron bollards with crowned ‘RBT’ monograms.

The Royal Brunswick Theatre bollards of 1828 on Ensign Street, photographed by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London in 2017

The prevalence of sailors in east London’s riverside districts was not new at the beginning of the nineteenth century, but populations did increase and living conditions declined. The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 left an estimated 100,000 seamen redundant from the Royal Navy. The Rev. George Charles ‘Boatswain’ Smith (1782–1863) came to the fore in addressing the lot of these sailors through evangelism. A seafarer himself in his teens who had served with distinction under Nelson in the battle of Copenhagen, Smith had become a Baptist missionary. He established a floating sanctuary on a remodelled sloop and took the former Danish Church in Wellclose Square for use as a Mariners’ Church. A witness to extreme poverty and deprivation, he was instrumental in the taking of a warehouse in Dock Street to establish an asylum for destitute sailors that opened in January 1828. Smith was also a pioneering advocate of temperance.

Paid upon coming ashore, sailors, both naval and mercantile, were prey to exploitation and theft by boarding-house and brothel keepers and others, a practice known as ‘crimping’ that was widespread and generally tolerated. Smith was determined to force reforms and had tried to introduce a system of approved boarding houses as used in other ports. In his eyes the Royal Brunswick Theatre and its predecessor, the East London Theatre, had been a haven for crimping. The collapse presented an opportunity. In September 1828 Smith convened a meeting on the site with a view to raising there ‘a General Receiving and Shipping Depot for Mariners’.[1] This was to be a religious mission, aiming at moral reform through reducing the influence of prostitution and drink. As such it was a late example of the Georgian impulse to improvement and control through institutional architecture. Alongside Smith were Captains Robert and George Cornish Gambier, RN, brothers, and nephews of Admiral James Gambier, himself an evangelical, and Capt. Robert James Elliot, RN, who was also a topographical artist. Appeals were launched in early 1829, aiming to unite ‘the Regularities of social Order with the moral Decencies of Life, the Principles of Christian Loyalty, and the Duties of Religion.’[2]

Within the year eminent naval and other figures had been recruited to promote fund-raising (first trustees included William Wilberforce) and the freehold of the site was obtained. But Smith, an uncompromising and combative character, fell out with George Gambier, the Treasurer, over the latter’s unworldly sympathies for Henry Irving’s radical Nonconformity that had led him to leave fund-raising to faith. Smith stepped down as Secretary and set up a rival Sailors’ Rest project leading other Dissenters to withdraw support for the Home. Elliot took charge as the Home’s Secretary and steered the project into Anglican safety. Hardwick was engaged and on 10 June 1830 Elliot laid a foundation stone. Hardwick conceived the project in stages, to be built gradually as funds became available, ultimately to provide space for 500 men, each with their own cabin or sleeping place. Progress was slow and the Home did not open until 1 May 1835, with accommodation for 100 men on its lower levels. The first sailors admitted were the crew of an American ship in St Katharine’s Docks. A peaceful atmosphere introduced by the ‘sobriety and steadiness’ of these ‘temperance men’ was broken a few days later by the arrival of English sailors, coming from India and bringing ‘intoxication, swaggering and noise’.[3]

The Sailors’ Home of 1830–5, Philip Hardwick, architect, from the British Workman, 1857 (courtesy of Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives)

The Sailors’ Home’s façade echoed that of the theatre in its bay rhythm and the ground-floor channelled rustication. It may even be that the lower-storey wall was not wholly rebuilt. Hardwick connected the outer bays with a portico of large cast-iron Doric columns similar to those he had placed at St Katharine’s Docks. These columns were removed in 1952. The central part of the basement was a vaulted store that survives as a bar. The main central space at ground-floor level was a waiting hall open to all seamen. It had a York stone-flagged floor with a grid of nine tall cast-iron columns. The floor and columns are both still partly extant, but concealed. This hall was also used for assemblies and worship, and had small box offices for payment and registration, where the men’s ‘characters’ were recorded. Flanking dormitories named ‘Bombay’ and ‘Calcutta’ had two tiers of cabins, probably drawing on the precedent of Greenwich Hospital’s accommodation for naval pensioners. On the originally comparably tall first floor a central dining and reading hall had a similar array of columns and was flanked by two more double-tiered dormitories (‘Canton’ and ‘Madras’). Upper floors were initially used for a school, lecture room and museum of ship models and curiosities. As inmate numbers grew in the 1840s the outer upper-storey rooms were gradually fitted up as further dormitories, and a single bath was introduced.

Basement vaults in the building of the 1830s, converted to use as a bar. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

Henry Mayhew, in a full description that was not uncritical of the Home’s management, noted in 1850 that seamen addressed the institution’s officers as friends not as superiors, and recorded a testimony from one among them that ‘the steadiest-going seamen will always speak well of the Sailors’ Home’.[4] Henry Roberts, closely familiar with the Home having acted as its architect in the 1840s when he was also the first architect of the pioneering Society for Improving the Condition of the Labouring Classes and responsible for model lodging houses, later acknowledged that the Sailors’ Home ‘must in some respects be considered the prototype of the improved lodging-houses.’[5] Annual numbers of boarders rose from 528 in the first year to 3,833 in 1842 and 8,617 in 1861. Most of the sailors were of British or North American origin, but not all. By 1862 there had been 544 boarders from Africa.

Land behind the Home had been leased in 1842 with a view to possible extension, and was used in the meantime as a skittle ground. Dock Street was widened in 1845–6 and parts of the new frontage were acquired between 1854 and 1862 when Edward Ledger Bracebridge, a Poplar-based architect, designed a new block facing Dock Street. Lord Viscount Palmerston laid the foundation stone on 4 August 1863 and the Prince of Wales opened the building on 22 May 1865. A commemorative stone plaque bearing that information is still to be found facing the hostel’s internal courtyard where it was moved, recut, in 1956.

View down Dock Street showing the Sailors’ Home extension of 1863–5, with St Paul Dock Street beyond

The outwardly Gothic and polychrome Dock Street building’s basement housed a navigation school, a recreation room and two baths. The ground floor had offices to the front, including a seamen’s savings’ bank, with waiting halls to the rear, the first floor a boardroom and officers’ mess room to the north, and a library and recreation hall to the south. The two upper storeys were laid out as a single room, the Admiral Sir Henry Hope Dormitory. This extraordinary space comprised four galleried tiers of sleeping berths or cabins (108 in all) to east and west of an atrium open to the roof with south-end staircases (see images in Historic England Archives). The gain in accommodation was 160 berths for an overall capacity of 502.

In 1874–5 a single-storey skittle alley to the rear was reconstructed, extended to the south and raised to be a three-storey and basement range to provide an additional dormitory for ships’ mates and a clothing store, sales of clothing from the Home having been introduced in 1868. John Hudson and John Jacobs, both of Leman Street, were architect and builder respectively. A drinking fountain near the northwest corner of what was the main waiting hall is surmounted by an inscribed plaque recording a benefaction of 1873 from William McNeil, a formerly resident seaman.

Drinking fountain and plaque on what was an internal wall of the waiting hall, photographed by Derek Kendall in 2019 for the Survey of London

By this time there were many other hostels for sailors, but the Sailors’ Home was the parent exemplar. Outside, crimping was still prevalent, and the Home was drawing more than 10,000 boarders annually. Ale was served, but there was no bar. It remained a Christian foundation, but not zealously so, aiming to ‘encourage habits of decorum, economy, and self-cultivation, and to contribute in educating [seamen] as missionaries of Commerce to the ends of the earth’.[6] Between 1879 and 1884 Joseph Conrad (Jozef Korzeniowski) stayed several times at the Home and studied in its navigation school. Conrad called the Home a ‘friendly place’, ‘quietly unobtrusively, with a regard for the independence of the men who sought its shelter ashore, and with no ulterior aims behind that effective friendliness.’[7]

Internal courtyard from the north, showing the 1870s range to the left, a surviving section of the 1860s building straight ahead and the back of the 1950s building to the right. Photographed in 2019 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London.

In 1893–4 the original building’s south range and a stable yard beyond were replaced by a Mercantile Marine Office, which building survives on Ensign Street. That sacrifice reduced the Home’s capacity to 300, a limit that had further to be reduced to 200 following a threat of closure in 1910 when the LCC stipulated improvements to the original dormitories, in particular for the provision of light. Murray, Delves & Murray, architects, oversaw works carried out in 1911–12 that involved the insertion of an additional floor in the Ensign Street block. Internal reconstruction formed a light-well above the ground-floor waiting hall, with structural steel carried down to the basement. Bars and a first-floor chapel were introduced and a house was demolished to permit the formation of windows in the Home’s north flank wall, which was faced with channelled rusticated render. Following this reconfiguration the establishment rebranded itself, incorporating as the Sailors’ Home and Red Ensign Club in 1912. Despite the reduced berths, the numbers of boarders continued to average more than 10,000 a year. By 1919 the Home had admitted a total of 639,005 sailors, 336,088 of them English, 51,388 from Sweden, Norway and Denmark, 18,500 from Germany, 11,376 from Russia, 2,483 from the ‘Cape and Mauritius’, 1,154 from West Africa, 7,958 from the West Indies, 2,523 from the East Indies, 1,914 from South America, and 1,387 from China and Japan. After this, the origins of the sailors were no longer recorded in annual reports.

More than 20,000 were boarded in 1933, usage that was sustained after the war when the merchant navy reserve pool was introduced, bringing seamen greater security of employment. Additional accommodation being needed, the Home’s architect, Colin H. Murray of Murray, Delves, Murray & Atkins, advised a comprehensive approach in 1937 and was asked to prepare plans for complete rebuilding. War meant postponement, but Murray did advance a scheme for rebuilding the Dock Street building in 1942.

By 1945 Murray was working with Brian O’Rorke on a more ambitious phased project for the replacement of the whole complex (now simply called the Red Ensign Club). This envisaged three slab blocks laid out on an offset H plan to make best use of the two street frontages, rising at the centre to twelve storeys for a total 307 bedrooms (no longer called cabins) above lower-level common spaces. LCC approval was secured, but in the post-war years building licences were not forthcoming. O’Rorke (1901–74), New Zealand born, had come to notice in placing joint third in the competition to design the RIBA’s headquarters and gone on to build a reputation for designing passenger-ship interiors. In 1946 he succeeded Edwin Lutyens as architect for the National Theatre, for which his designs remained unbuilt. He took over as architect for the new Club, leaving Murray, Delves, Murray & Atkins in charge of maintaining the existing buildings.

Costs kept rising with inflation and a diminishing number of boarders gave rise to concern in 1949 that expansion was no longer warranted. O’Rorke scaled down the plans by two storeys, and a licence for the first phase was granted in 1950. A new problem arose when the Merchant Navy Welfare Board was unable after all to contribute funds. With a shortfall of £35,000 of an estimated £275,000, and costs still rising, in 1951 O’Rorke suggested rebuilding the Dock Street range with the taller central block to its rear for £160,000 to prevent further delay. This was agreed and Charles Price Ltd was given the contract for the new building for £179,488 in March 1952. First Hardwick’s Ensign Street block was re-modernised, to plans by Murray with R. Mansell as contractor. A staircase was inserted in the northeast corner of the ground-floor lounge, which was otherwise laid out with a billiard table and a ‘television set’. The Dock Street rebuilding ensued from 1954 and was completed in 1957 for a final cost of £218,400. Even so, the central block had also had to be abandoned, the new capacity was just 240 and there was a deficit of £63,000.