The former ‘Colonial House’, 17 Leman Street, Whitechapel

By Survey of London, on 23 October 2020

In the nineteenth century, East London was referred to as the Deutsche Kolonie by the German community and ‘our London ghetto’ by the Jewish community. For British sociologist Michael Banton, by 1955 Stepney could comfortably be regarded as ‘The Coloured Quarter’, its identification as a centre for post-war Afro-Caribbean settlement coming under wider public scrutiny as a result of regular letters in the national press criticising government authorities for inaction in the provision of housing.

A number of groups commissioned surveys which aimed to assess the welfare and living conditions of the East End’s Black community, concerned about issues of segregation in the built environment and acutely aware of the dangers of ‘ghettoization’. The experience of the unofficial ‘colour bar’ on resident Black seamen was of especial interest in these studies. During the Second World War and afterwards, Britain politicians did not generally and overtly support segregation. Yet discrimination was by no means absent in British space, and a de facto segregation cut across both private and public urban spaces. Reports suggested that the bar was most evident in port cities like London. For Black seamen in wartime and post-war East London, the existence of a colour bar was indisputable.

From the 1940s, the so-called ‘coloured question’ in London’s East End was a matter of strategic importance for government authorities. The provision of accommodation for seamen was one aspect of this question. Seamen’s hostels had become an issue during the war, responsibility for the ‘special wartime measure’ for seamen from the colonies given over to the Colonial Office, with increasing resources diverted to attend to these men after the Colonial Development and Welfare Act of 1940 was passed. Colonial labour to support the war effort had been actively sought, with recruitment calls made in British colonies in the West Indies and West Africa, yet onshore accommodation for sailors prioritised white British seamen. In an attempt to redress this imbalance, 17 Leman Street, Whitechapel, was acquired by the Colonial Office in 1942 and converted into the only seamen’s hostel for Black men in London. For less than a decade, this small government-sponsored hostel provided thirteen beds for seamen from British colonies in the Caribbean and West Africa.

17 Leman Street in 2007, photograph by Danny McLaughlin, from surveyoflondon.org

The Colonial Office was in fact involved in the establishment of a national network of ‘Colonial Houses’. Whilst often small in scale, seamen’s hostels such as the one in Whitechapel can be seen as flashpoints for discontent as the national identity and rights of Black migrants from British colonies were contested by employers, activists, local and government authorities and the men themselves, against the backdrop of emerging understandings of race relations in the United Kingdom.

Built in 1861–3 as a German Mission School, the two-storey hostel was situated at the north end of Leman Street, near Whitechapel High Street, until demolition in 2008 to make way for a twenty-three storey tower hotel of short-stay serviced apartments (15–17 Leman Street). Despite functioning for less than a decade as a government-funded hostel that was the subject of some local controversy, Colonial House was well-documented as a result of its connection to the Colonial Office and a group of tireless East London campaigners. Bert Hardy made a series of black-and-white photographs in 1949.

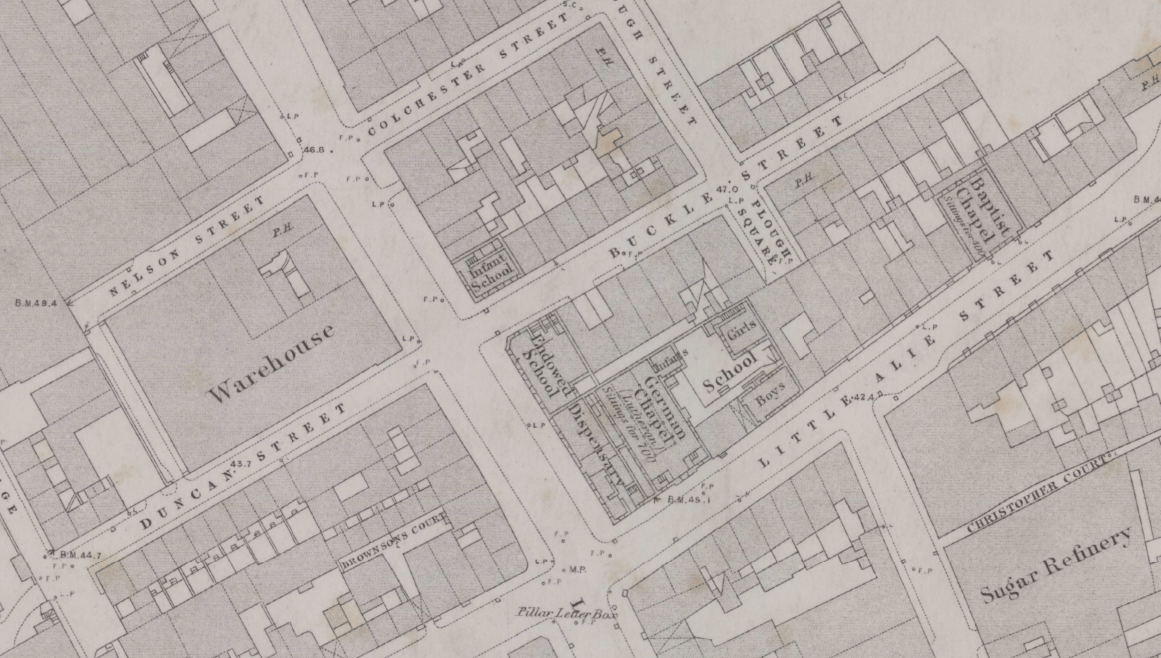

Paternalistic welfare provision for migrant communities was well-established in the Leman Street building long before use as the Colonial House hostel. It was constructed to host education, recreation and acculturation activities for diasporic groups, firstly German Christians and then East European Jews. The German Mission Day School replaced an eighteenth-century tenement and bakery on the site in 1861–3. The purpose-built school was one of a handful of educational buildings clustered on Buckle Street and the east end of Alie Street. This group of buildings was fashioned primarily to serve a large local German population that was closely associated to the sugar-refining business during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The school was designed by Edward Ellis, a London architect better known for his work on offices and warehouses. With a long elevation to Buckle Street and a steeply pitched gable roof, the two-and-a-half storey building assumed an institutional Gothic Revival style, typical of its time. It was formed of London stock brick with black- and red-brick headed arched openings. A large ground-floor corner schoolroom was accessed through decorated double-doors located in a narrow wing extension facing onto Leman Street. An office and further large schoolroom were on the first floor. The top floor provided separate living accommodation for the school’s two teachers. In its unassumingly reserved exterior, the school was matched by other buildings constructed for the local German community, none of which sought to broadcast their ‘alien’ status.

Ordnance Survey map of 1873 showing the infant school at the junction of Leman Street and Buckle Street

By the end of the century, with many German families having moved out of Whitechapel to more salubrious suburbs and many free English schools in operation, leaders concluded that the ‘German Poor School’ should be given up. It closed in 1897 and the schoolhouse was let out for commercial purposes, the rent channelled into funding German education in other parts of the capital.

By 1903 the former school building was in use by the Jewish Working Girls’ Club (JWGC). The purchase of the leasehold was made possible through the support of one individual, (Lady) Julia Henry, daughter of the prominent Jewish-American philanthropist, Leonard Lewisohn. Henry’s support was prompted by an anxiety to show American goodwill towards English Jews in the light of tightening immigration policies in the US, which restricted Jewish movement into the country as religious refugees. The former Mission School was adapted without significant architectural alteration to suit its new purpose by the architect M. E. Collins, who, on completion, reported that the Club contained ‘every accommodation, including the usual recreation rooms, a kitchen, scullery, library and other rooms’. [1] The day-to-day running of the Club was reliant on voluntary contributions and teachers were mostly volunteers from the well-meaning and already settled middle classes, concerned that the assimilation of poor Jewish children from Eastern Europe was occurring neither rapidly nor effectively enough. With 160 girls regularly attending evening and Sunday classes in such subjects as needlework, cooking, Hebrew and religion, singing and drilling in the early 1900s, the Club ‘exceedingly flourish[ed]’ well into the 1920s. [2] The JWGC appears to have continued on until at least the late 1930s before closure around the beginning of the Second World War, the Jewish exodus from East London ‘well-nigh complete’ by the late 1950s.

Requisitioned for use by the War Office soon after the outbreak of war, the former school became a hostel for Black seamen from the British colonies in 1942. In spite of a proliferation of local seamen’s hostels, ‘coloured colonials’ were frequently turned away or were reticent to take up beds reserved for them in larger hostels, aware that their very presence might result in social unrest, as it had in the recent past.

The Colonial Office hostel at Leman Street was intended for thirteen seamen, whose stay was limited to a maximum of three weeks on the basis that they were only temporary residents awaiting their next contract at sea. Accommodation included a basement dining room and kitchen, a ground-floor common room and office, with a large open dormitory, and a small adjoining bedroom on the first floor. The self-contained second-floor flat once home to the German teachers was assigned to the hostel’s warden. Equipped with a billiard table and piano, the common room was intended to serve an important social function, where, it was envisioned, ‘men can sit and talk’. But in the extent of its provision and the effectiveness of its organisation, the small hostel fell woefully short, dogged by problems from its inception and only deepening after the end of the war. Three successive wardens failed to maintain order in the house as men arriving at the hostel often struggled to find places on ships leaving the port, overstayed and grew restless. Although intended only as a place of short-stays for ‘the floating population’, the hostel frequently housed teenage stowaways and those with longer-term ambitions to settle permanently in the country. Local boarding-house keeper Kathleen Wrsama despaired at the lack of support given to these men, who arrived with little or no knowledge of the culture and institutional systems in England. She recalled, ‘The Colonial Office opened a house and you know what it was known as? It was known as the government gambling den. I used to laugh at that. They did nothing for the poor boys’. [3]

Cafés around the west end of Cable Street, often run by former seamen, formed a valuable network of informal social spaces through which private lodging places could be found. A pattern of friendly association brought men into this alternative economy, as former colleagues set up unregistered lodging houses hosting a circuit of friends and friends of friends who arrived after a period of time at sea. Along Cable Street, three-storey bomb-damaged terraced houses in a state of considerable disrepair accommodated cafés on the ground floor, dancing clubs in the basement, and bedrooms on the upper floors. In 1944, thirty-four such humble cafés were identified. African-origin men were the most affected by deficient housing conditions. Derek Bamuta noted, ‘I have reason to suspect that a lot of them actually sleep in bombed out houses’ after having wandered the streets until the early hours of the morning.’ [4] By 1950, those living in unofficial lodgings in the Cable Street area were deemed to be enduring the worst possible conditions. Once settled in temporary accommodation, there were few opportunities for Black tenants to move out of the area; many white landlords would not accept them.

Much to the dismay of local activists such as Edith Ramsay, a councillor, and Father St John Beverley Groser, who saw Colonial House as tokenistic, by 1946 inefficient management of the hostel had caused the Colonial Office to quietly close it only for it to be hastily re-opened soon after. For Ramsay, this episode was evidence of a dereliction of public duty and the abandonment of principles set out in legislation such as the Colonial Development and Welfare Act 1940 which shifted government policy away from a laissez-faire attitude to the colonies and its peoples towards investment in their social, physical and economic needs. The hostel was consistently oversubscribed, with Ramsay reporting that up to forty men could be packed into the building using mattresses on the floor in the mid-1940s. It only catered for a very small percentage of non-resident seamen, and left the needs of the wider resident ‘coloured’ community entirely unattended.

Closure of the tiny Colonial House became representative of what was perceived to be central government’s confused policy and piecemeal approach to the issue of housing British ‘colonials’ in the UK. After a visit to the Leman Street hostel in 1944, a shocked civil servant, Frank de Halpert, exclaimed, ‘Here we are in the greatest city in the world, with the largest colonial empire, and that is the hostel we offer!’ Linking it to a broader political disregard for British territories overseas, he assessed ‘it is on a par with our [political] treatment of the colonies to which in Parliament we devote one or at most two days per annum’. [5]

The London County Council (LCC) also recognised the housing shortage that was affecting growing numbers of Afro-Caribbean men, and particularly seamen, who continued to arrive in the East End. But it held that responsibility to provide suitable hostels for this group lay firmly with the Colonial Office. On the basis that the East End Welfare Advisory Committee would provide essential advice on the running of the hostel, the LCC persuaded the Colonial Office to defer permanent closure of the Leman Street hostel. With the inadequacy of the hostel provision more widely accepted than before, after re-opening discussions turned to consider the construction of a large purpose-built hostel to accommodate approximately 100 men. The bomb-damaged site of St Augustine’s Church on Settles Street was surveyed, as was a property on Wellclose Square, and another on Dock Street, but at the last minute the Colonial Office unexpectedly withdrew its support for the scheme. The existing thirteen-bed hostel muddled on.

Closure of Colonial House was again announced in October 1949. Hopes of a new centre had long since dissipated; blindsided local campaigners felt their considerable efforts to improve conditions had been shamefully undermined. The Colonial Office argued that it had ‘no authority to provide accommodation for colonials permanently resident in the UK and this was primarily a matter for local authorities.’ [6] At this time, while the ‘coloured question’ at last received substantial media attention, the Black population of Stepney had in reality already begun to decline, slowly migrating out of bomb-stricken environments as the demolition of properties earmarked for redevelopment began.

After the Colonial Office’s eventual retreat, in the 1950s the hostel operated briefly under the private management of a West Indian, Donald Watson (or Watkins) of Ladbroke Grove, before transferring to the LCC for use as a reception centre for ‘stowaways’, a scheme partially administered through the London Council of Social Service. By 1959, the centre had closed and the building was used for commercial purposes by H. Bellman & Sons, dressmakers.

The apart-hotel of 2014–16 at 15–17 Leman Street is the glazed slab to the left of centre. Photograph of 2016 by Derek Kendall for the Survey of London

*This blog post is expanded upon in the article ‘Accounting for the hostel for “coloured colonial” seamen in London’s East End, 1942–1949’ published in a special issue of National Identities on ‘Architecture, Nation, Difference’ (October 2020). The first fifty downloads are free using this link.

1 – Jewish Chronicle, 1 May 1903, p. 22

2 – Jewish Chronicle, 16 March 1923, p. 38

3 – Black Cultural Archives, BCA/5/1/24

4 – Derek Bamuta, ‘Report on an Investigation into conditions of the coloured people in Stepney (1949). Prepared for the Warden of the Bernhard Baron Settlement’, Social Work, January 1950, pp. 387–95

5 – Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archive, P/RAM/3/1/6

6 – Black Cultural Archives, Banton/1

One Response to “The former ‘Colonial House’, 17 Leman Street, Whitechapel”

- 1

Close

Close

Fantastic reading it was originally on my doorstep and didn’t realise what history was attached to it!